This is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real places are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and events are products of the authors imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

251 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10010 Text copyright 2019 by Ching Yeung Russell All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Little Bee Books is a trademark of Little Bee Books, Inc., and associated colophon is a trademark of Little Bee Books, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America LAK 0519 First Edition 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 978-1-4998-0875-9 yellowjacketreads.com To Blake and Morgan, my grandchildren,

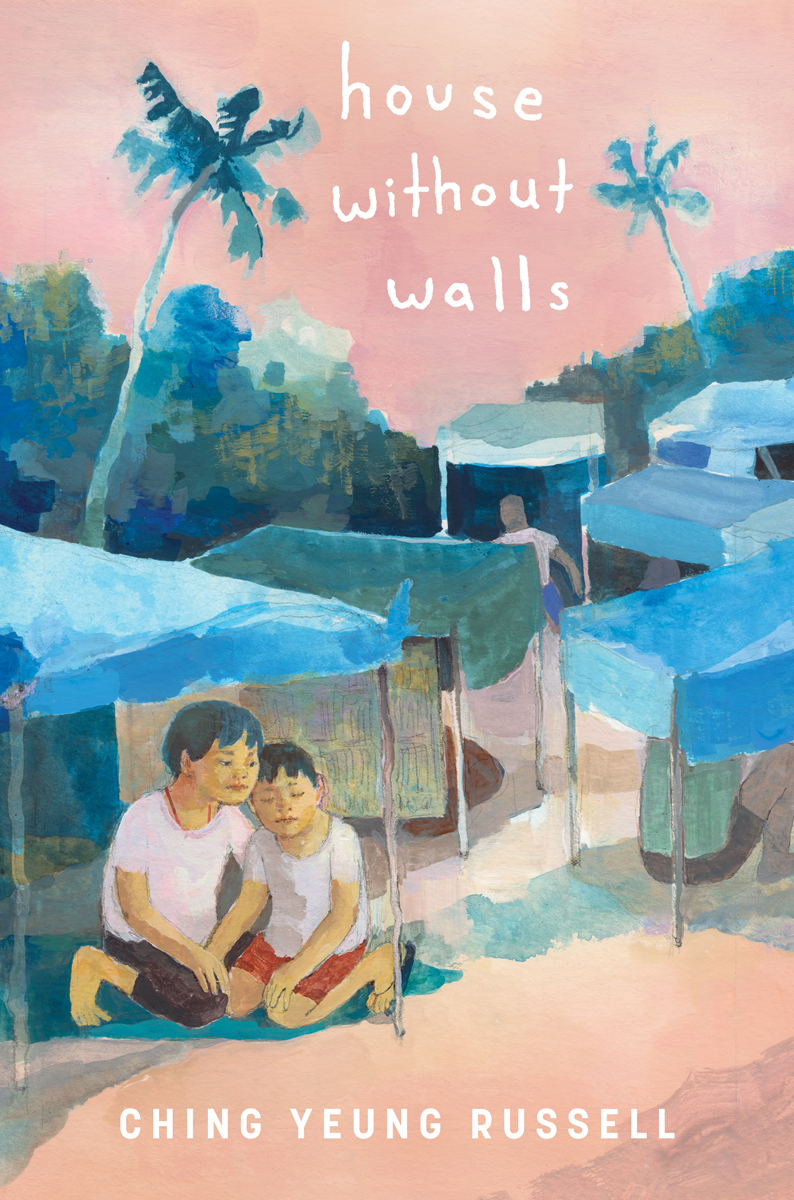

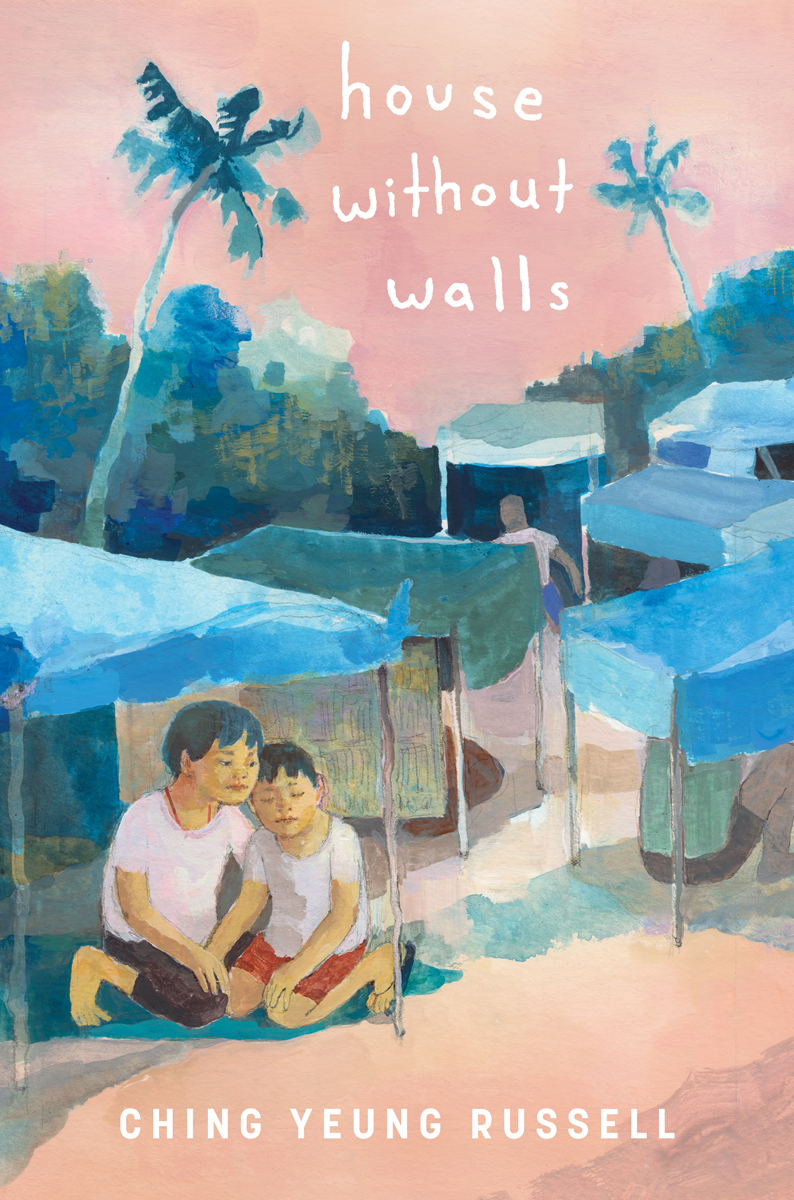

and to all the refugees in the world In memory of my cousin, Chi-Yen Chan CONTENTS PROLOGUE I met Lam and Dee Dee (their fictionalized names), the protagonists in this story, in 1986. I knew they had been boat people from Vietnam. At first, this didnt excite me. Later, when we grew closer, they talked about what had happened to them while they were on their journey. Theirs was a truly hazardous experience, one that most people could not even imagine. Thats why I decided to work on their story.

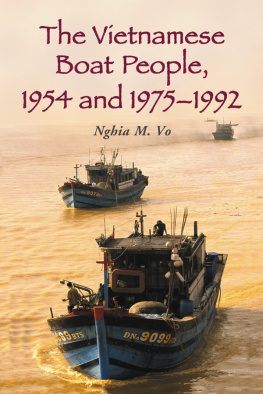

I interviewed them both many times, asking them why they wanted to leave their hometown and about the circumstances in their country in 1979, when they tried to escape. The information that follows may aid you in your understanding as you journey through this book. The North Vietnamese Communists took over Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, on April 30, 1975. The new Communist government mostly targeted ethnic Chinese, also called Hoa, Han, or Chinese Vietnamese, and forced them out of the country. Many of these ethnic Chinese lived in the Cholon district of Saigon. They had their own traditional culture, language, and schools, even though their schools were required to offer Vietnamese lessons.

Although they made up only about 5.5 percent of the population in South Vietnam (more than half of them were Cantonese, and the Teochew, Hakka, Hokkien, and Hainanese made up the rest), since they were favored by the French when they colonized Vietnam, they controlled up to 70 to 80 percent of the commerce. The new government closed down the privately owned businesses in early 1978. They seized their businesses and properties and sent many businessmen to reeducation camps, which were located in the remote countryside. Many of those who were sent there didnt come back. Some of them died from hard work or snake bites, or they were killed by the land mines. Thats why they wanted to escape.

Some young men, like Daigo , the older brother in this story, fled the country to avoid being drafted to fight against China at the border between China and Vietnam in 1979, in which tens of thousands of young people died on both sides. Even though the war officially ended in March of 1979, a couple of months before Lam and Dee Dee escaped, some feared that the war would erupt again and that they would be conscripted to fight. Some people who left Vietnam were seeking political asylum. Those who had fought for the South Vietnamese against the Vietcong (North Vietnam Communists) or who had aided the Americans during the war were considered to be enemies of the country and were sent to reeducation camps or prosecuted. Some people fled their country because they didnt want to live under communist rule and wanted to seek a better life for themselves and their children. Thats why more than one million Vietnamese and ethnic Chinese left Vietnam.

Most of them fled by boat. According to my sources, people over sixteen had to pay eight taelsmore than ten ouncesof gold for a seat on a boat to escape. For children under sixteen, the price was six taels. The gold was reportedly shared between the new government and the people who organized the escapes. After giving the government their share, they would use part of the gold to buy a boat and hire a crew to operate it for the voyage. Therefore, these escapes were open.

But sometimes these escapes were arranged on the black market, and only the organizers were paid. In that case, the authorities would try to impede these escapes. Thats why people were very careful. Most of the boat people didnt make it. Many of them died at sea from starvation, dehydration, or drowning, or they were killed by pirates. Even if they were lucky and made it to one of the Southeast Asian countries, many were turned back toward the sea.

Some said initially Singapore was the first country to prevent the boat people from entering its coastlines because of their limited land. Singapore provided the refugees with water, food, and fuel before turning them away. (Later, however, they couldnt prevent others from landing. Between 1975 and 1979, nearly five thousand refugees came to Singapore, most of whom were picked up by commercial ships.) However, after Singapore first turned away the boat people, other countries soon began to refuse them sanctuary. Since the coastline of Malaysia is long, many refugees landed there easily when they first spotted land. The Malaysian government let them stay temporarily and waited for other countries to accept them.

But the progress was too slow. They could not adequately provide for the great number of refugees who arrived in this burgeoning armada. Thats why they had to tow the latecomers, with water and food provided, back to sea, hoping they would land elsewhere. Refugees were housed in camps in Hong Kong, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Some refugees had to stay in these camps for more than ten years. According to published reports, over twenty-one years, more than 840,000 refugees landed in the countries of Southeast Asia.

More than 755,000 of these were resettled in the West, and more than 81,000 were eventually repatriated back to Vietnam under an agreement with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Neither Lam nor Dee Dee knew the places where they settled down temporarily in Malaysia. When they lived in the camps, they witnessed people dying from snake bites, from diarrhea due to unsanitary conditions, or from drowning while fishing on rafts that they made. In addition to hearing their story, I also visited a refugee camp in Hong Kong in 1992. (There refugees could learn English or simple skills inside the camp and some even had permission to go outside the camp to work.) Despite the fact that some refugees who had fled Vietnam up to a decade before were still there and were facing being sent back to Vietnam under a plan by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, they told me their stories about how they got out of Vietnam and how horrible their journey was at sea. House Without Walls is a story based on Lam and Dee Dee s accounts, other first-person narratives I heard during my visit to the Hong Kong refugee camp, and my own creativity.

In writing this story, I have gained tremendous respect for all people throughout the world who risk their lives for freedom and a better life. In House Without Walls , I strove to portray the perilous journey that some of these refugees faced when they fled their homeland. There are many more cruel details of the escapes. Because this book is for young readers, I edited out some of the more shocking details of cruelty I heard about, but I certainly did not shy away from some of the grittier aspects of the refugee experience. I also emphasized that no matter what life throws at them, children are childrenthey will still find a way to play, to laugh, and to find joy despite gruesome circumstancesdespite living in a house without walls. PART ONE May 10, 1979

Next page

This is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real places are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and events are products of the authors imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

This is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real places are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and events are products of the authors imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.  251 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10010 Text copyright 2019 by Ching Yeung Russell All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Little Bee Books is a trademark of Little Bee Books, Inc., and associated colophon is a trademark of Little Bee Books, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America LAK 0519 First Edition 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

251 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10010 Text copyright 2019 by Ching Yeung Russell All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Little Bee Books is a trademark of Little Bee Books, Inc., and associated colophon is a trademark of Little Bee Books, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America LAK 0519 First Edition 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.