Contents

Guide

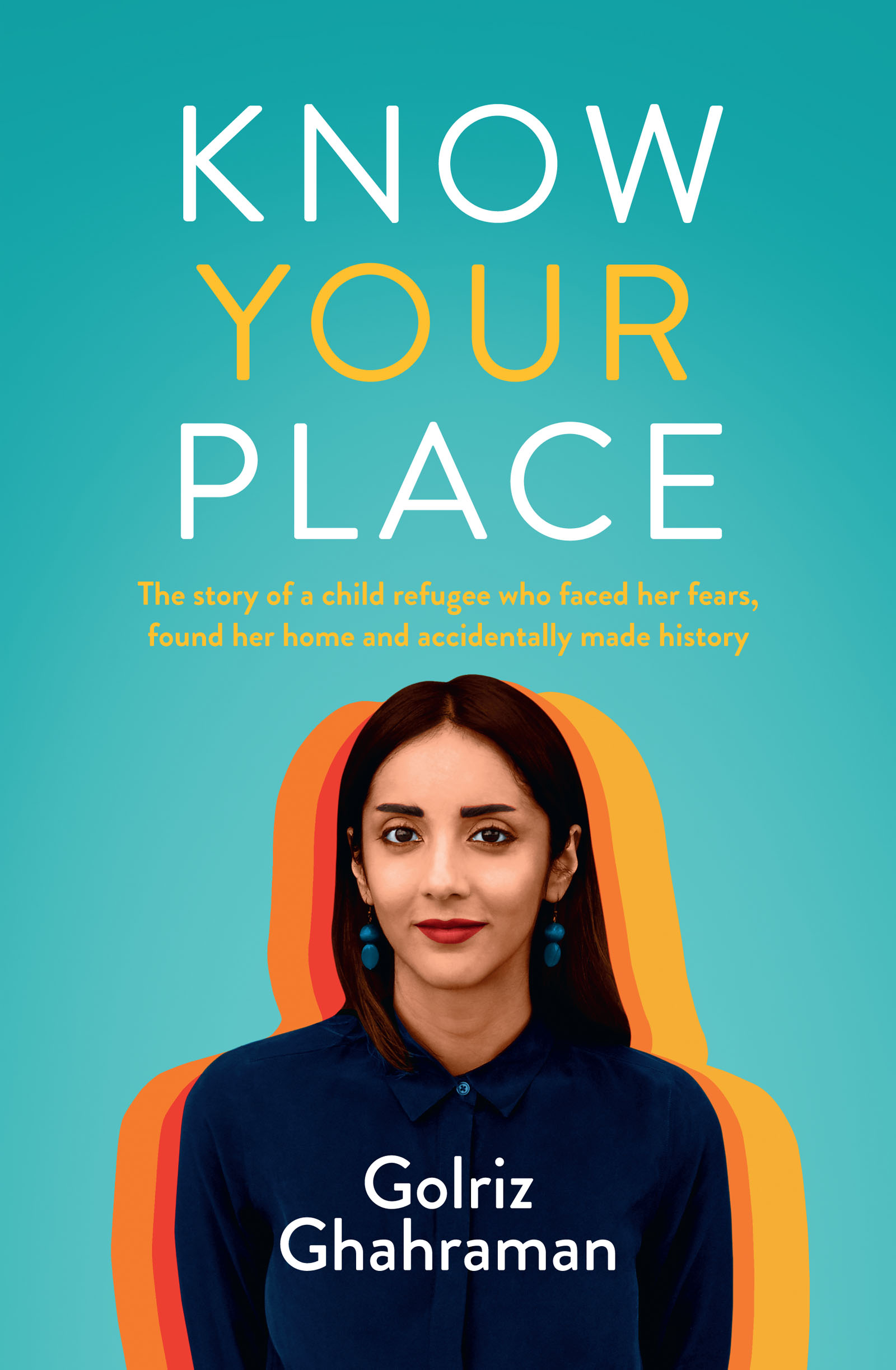

For my parents, Maryam and Behrooz, who lost their home,

family, friends, professions, and even language, because they were

not willing to raise a little girl in oppression.

Contents

My life, as it is now, began the day I left Iran at the age of nine. Ive spent my adult years protecting that little Iranian girl from being erased, because that day was also the day life as she knew it ended. She never saw her friends, her cousins, or her school again. She had to learn most truths about daily life over again. Little of what had shaped her as a person who she was or wanted to be would exist in her new home. In fact, she would only encounter a small roomful of people who looked like her, knew her language or world, either in person or in fiction.

I think of that nine-year-old girl often and wonder where she would be now had her life not been unhinged so suddenly, so deliberately, when she boarded that plane. Still in Iran, now in her thirties, she would speak and think and dream in Farsi, abilities I lost so fast it was almost traumatic once I realised they were gone. She might be a lawyer too. That much is possible. Maybe the urge to rebel and speak out is innate in us, so the oppression would be too hard for her to bear in silence. Maybe that oppression has made her stronger, a real-life freedom fighter, which I cant claim given that all this freedom Im now afforded in Aotearoa takes some of the rebellion out of the outspokenness. Maybe she paid that terrible price we were all fearful of: ending up in the notorious Evin prison.

Or perhaps, under the weight of convention, she would be married and have children now. I wonder, does knowing what is expected of you make it easier to feel contented or complete?

I recall that nine-year-olds strong sense of self, which has never been whole in me again. Leaving my homeland as a child has suspended me between worlds, so it is never possible for me to be fully Iranian but the experience of having fled Iran is exactly why I will never be fully anything else either. The experience of leaving makes the identity of a foreigner forever more acute. It binds us to other children of foreign origin as a tribe, more so than to our own original or adopted cultures. Given I will never know who I would have been had I not left Iran, I must have begun existing the day we flew out of our then homeland, never to return.

That day was greeted as a triumph. It wasnt an ending; it was a fresh start. Getting out was something everyone around me spoke about for as long as I could remember. Enforcement of what the regime called Islamic law had begun in earnest the year I was born, as did the bloody eight-year war waged against Saddam Husseins Iraq. My childhood was peopled with a generation of adults in a state of perpetual shock as new oppressions and indignities flooded their lives, as an army of amputees returned from war, as weeping mothers mourned their martyred sons. Once in a while, people would disappear. That meant either exile, prison, or, as wed discover some time later, death at the hands of the regime. For us, it was exile that released all that pressure and fear that had defined our daily lives. No wonder then that I walked onto that plane determined to shed everything, the good with the bad. What wouldnt you give to be free from fear?

My memory of that morning in late September 1990 begins with waking up in my uncle Mammads apartment in Tehran. It was before sunrise, cold and half-dark. We were drowsy automatons, going through the motions of getting dressed and putting the last of our things into already-packed bags, while being careful not to wake Mammads daughters, who were around my age and had school later that day.

Tehran traffic was notorious even then, even at dawn, so we were leaving hours before our flight. Driving in my uncles car, I remember the grey smoggy sky, the crush of apartment blocks, and roads with so many vehicles jammed on them that the lane markings were meaningless.

I hadnt grown up in Tehran. I had spent my childhood moving between Mashhad and Urmia, where my dads and mums families were, and thought of these places as home. Mashhad in the north-east near the border with Afghanistan is a big dusty suburban city, nothing like the cosmopolitan Tehran. Its famous as the second city of Shia Islam. Urmia is right across the country in the north-west, almost bordering Turkey. Green and lush, its home to an open secularism that comes with diversity, where Sunni, Shia, Jewish and Armenian communities happily mingle. But the final scenes of Iran in my mind are of that tense drive in the grey Tehran dawn.

Tehran was the last of three rounds of goodbyes we made. At no point did we tell anyone of our intention to flee, but no one was in doubt about that. It was an extraordinary expense for people like us to go on an overseas tour to begin with, and truly bizarre to go around conscientiously saying a fond farewell to people in person before what was supposedly just a two-week trip. In Mashhad, where I was born and we lived, we took a few days to visit my parents best friends and close relatives, including my grandma and two uncles families. I remember the extended tight hugs; the kisses on each cheek, then each cheek again; the squeezed hands; the welled-up tears fought back. These goodbyes were profound for their permanence.

I know the hardest goodbye that round was my dads to his mum, Maman Naz (lovely mama), as she was to me. He had been a self-professed and proud mamas boy his whole life, and they remained close until she passed away in October 2017. Since we never felt safe enough to go back into Iran, he never got to see her as her health declined, even when she was moved to hospice care. He couldnt go home for the funeral.

As difficult as those Mashhad goodbyes were, they were a picnic compared to the harrowing scene at Urmia airport before we flew to Tehran for our final leg.

My mother is the middle child of seven. They grew up largely on vineyards in Western Azerbaijan, which my grandmas family had owned for generations. The women of my mothers family are passionate people, remarkably loving and extraordinarily close to one another. We split our time between Mashhad and Urmia during my childhood in Iran, because my mother could hardly bear to be apart from them. That closeness seems to be deeply rooted in their Kurdish heritage and a deep connection with their homeland the vineyards of Western Azerbaijan. I always felt like an observer of this, since I never became proficient in their native dialect. But even being a little on the outside, the warmth of their familial culture was always electric.

Even though Iranian vineyards couldnt make wine after the revolution, my grandmother held on to them as well as growing other kinds of fruits and walnuts. We spent a lot of time there on the land, the whole family chatting and preparing food, eating and laughing hysterically at a series of much-repeated in-jokes. There was generally a party on weekend nights. Members of the enormous extended family took turns hosting, and we all danced the traditional Kurdish line dance with scarves. All this happened at fever pitch on our last short visit before leaving the country.

My mother always said she married a man from across the country so she could get away and find her independence, but I think moving to Mashhad only intensified her sense of belonging to her own people, and they to her. When we left, the tears came hot and fast. Almost the whole family was there: her two sisters, her brother, all their children, her aunts, and their adult children. My grandmothers two youngest children, my aunt and uncle, had escaped the country soon after the revolution. She hadnt seen either of them for a decade, and still felt that loss keenly. At the airport, she was visibly distraught, though trying hard to hold it together for my mum as we said goodbye. It was a whirlwind, given the number of people. I felt overwhelmed, as I usually did with the emotional openness on that side of the family. Id never been too demonstrative, and I remember feeling guilty that I wasnt crying and clutching at everyone the way they were all doing. I also remember, most vividly, that my little grandma had to be restrained by security, because she kept walking through the barriers beyond where only ticket-holding travellers could go. She kept ignoring everyone and walking faster, calling for my mum to turn around so she could get a final look at her face. They were speaking in their dialect, Azeri, which I understood enough to know that they were reassuring each other, laughing about the next time we would all sit and eat my grandmas giant Turkish meatballs together. I felt lucky to be permitted in that inner sanctum; it was unconditional love made palpable, so it was harrowing to have it ripped away. We never ate meatballs with my grandma again.

Next page