Published by Otago University Press

Te Whare T o Te Wnanga o tkou

Level 1, 398 Cumberland Street

Dunedin, New Zealand

www.otago.ac.nz/press

First published 2020

Copyright Jenny Coleman

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

ISBN 978-1-98-859226-8 (print)

ISBN 978-1-98-859286-2 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-98-859287-9 (Kindle)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand. This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher.

Published with the assistance of Creative New Zealand

Editor: Gillian Tewsley

Indexer: Lee Slater

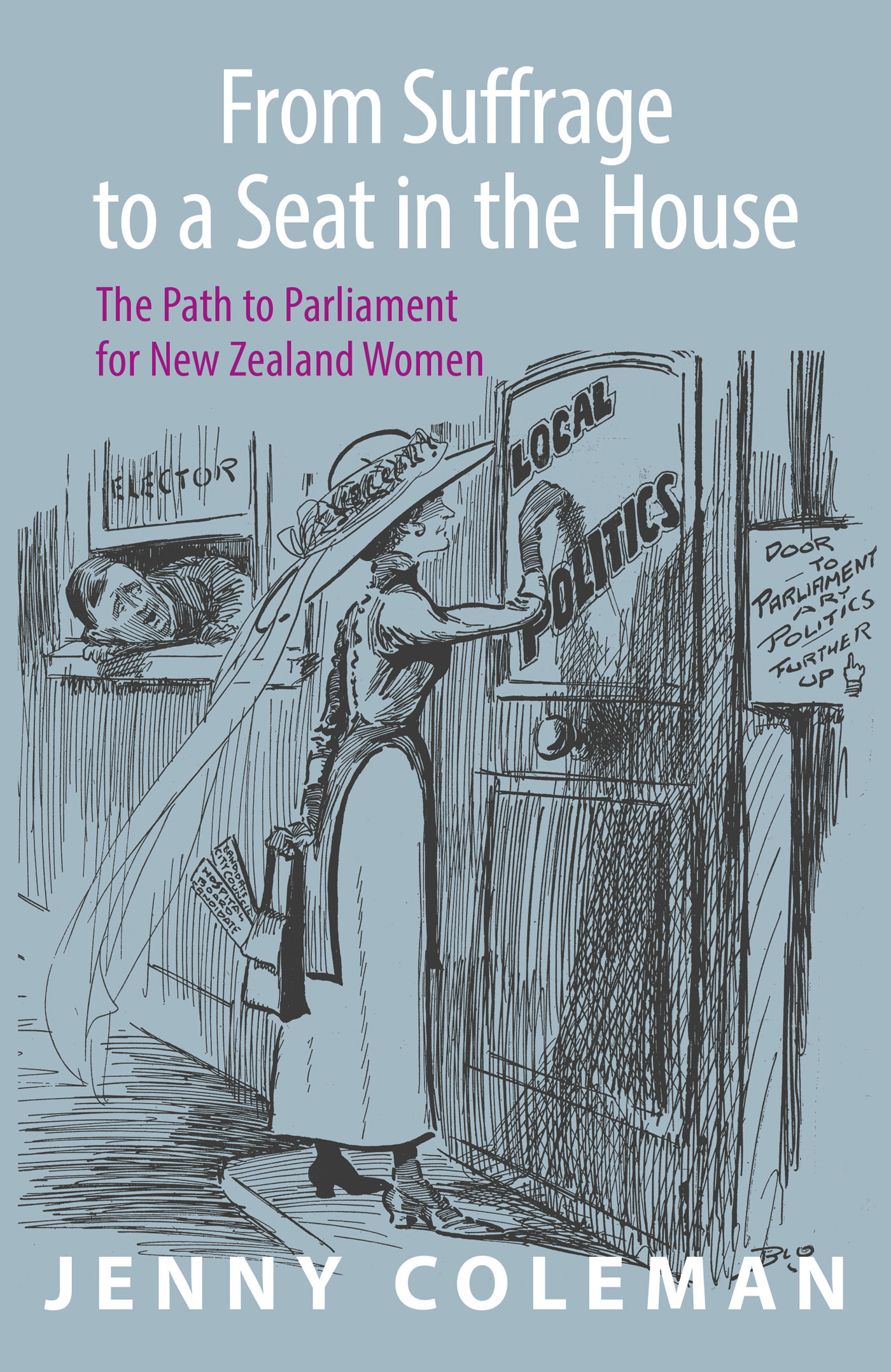

Cover: Behold! She stands at the door and knocks. William Blomfield, 18661938, H-712-009, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

Ebook conversion 2020 by meBooks

CONTENTS

Showing my lady to a seat

Passionate philosophical parliamentary debates, 1852 to 1893

The logical conclusion to female franchise, 1894 to 1896

Serving their political apprenticeship, 1897 to 1910

The full privilege of citizenship, 1911 to 1919

Petticoated candidates, 1919 to 1933

Our first lady member, 1933 to 1935

The ungallantly long hesitation

Women members of the New Zealand House of Representatives, 1933 to 2019

F irst I would like to thank my academic colleagues for their enthusiastic responses to my work in progress sessions at various Women Writing Away retreats. This book is only a part of what many of them were expecting, so I humbly request their patience as I continue to research and write on womens struggle to achieve a voice in Parliament. I am enormously grateful to the anonymous readers who engaged with several very different manuscripts and whose generous suggestions have resulted in the emergence of this book. It has been an absolute pleasure to work again with Rachel Scott and with Vanessa Manhire and the team at Otago University Press; I could not ask for a more professional and supportive publishing experience. Thanks too to Gillian Tewsley for her invaluable assistance with editing.

I am grateful for the support I have received toward research for this book, particularly during my research sabbatical in 2017, from the Office of the Pro Vice-Chancellor, College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Massey University.

I would like to acknowledge the support I have received from the following institutions: Alexander Turnbull Library; Archives New Zealand; Auckland Libraries Heritage Collection; Canterbury Museum Library; Christchurch City Libraries; Massey University Library; National Library, in particular the Papers Past and Parliamentary Papers online archives; New Zealand Electronic Text Collection; New Zealand Parliament Historical Hansard online archive; Ng Taonga Sound and Vision; Parliamentary Library, Wellington.

Finally, I would like to thank my partner Mary Nettle for putting up with many months of lost opportunities to play together in the garden or walk in the bush while I retreated to my study to write.

| AJHR | Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives |

| ATL | Alexander Turnbull Library |

| JAJLC | Journals and Appendices to the Journals of the Legislative Council of New Zealand |

| JHR | Journals of the House of Representatives |

| MHR | Member of the House of Representatives |

| NCW | National Council of Women |

| NZPD | New Zealand Parliamentary Debates (Hansard) |

| WCTU | Womens Christian Temperance Union |

| YMCA | Young Mens Christian Association |

| YWCA | Young Womens Christian Association |

INTRODUCTION

Showing my lady to a seat

But everybody that was anybody knew that votes for women meant, rather sooner than later, seats for women, elected with precisely the same wisdom and unwisdom that sent men to parliament. And the only thing any epitomising historian in the far future will note as surprising about New Zealands conduct in the matter is its ungallantly long hesitation to show my lady to a seat. MATANGA, 16 September 1933

I would like to warn honourable members, however, that women are never satisfied unless they have their own way But it would be another 15 years before women could vote in general elections, a further 26 years before the Womens Parliamentary Rights Act 1919 was passed, which entitled women to be elected as members of Parliament, and 14 years after that when Elizabeth McCombs proudly took her seat in Parliament. From Suffrage to a Seat in the House tells the story of how women achieved the right to stand for parliamentary election and their struggle to take a seat in the New Zealand House of Representatives.

Womens exclusion from Parliament dates from the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852, passed by the British Parliament, under which any person who qualified as an elector also qualified to be elected as a member of the House of Representatives. However, at that time the franchise was restricted to males aged 21 and over who owned property and who were registered to vote. Barring women from Parliament, both as voters and as elected representatives, was a denial of the basic right of women to share the same political rights and privileges as men. The journey to full parliamentary citizenship for women in New Zealand was marked by constant prejudice and debate, slow shifts in public opinion and small hard-won gains. But opportunities to chip away at long-held prejudices arose many times during the nineteenth century in debates on liquor licensing, educational reform and marriage law reform. The spectre of women in Parliament was raised as an anathema during debates on womens franchise, often as a deliberate ploy to undermine support for the franchise. Of the womens suffrage bills presented during the 1880s and early 1890s, four contained clauses that specified womens eligibility for parliamentary election and, of these, two were clauses that explicitly barred women from being eligible to stand for a seat in the House. As Chapter 1, Passionate philosophical parliamentary debates, 1852 to 1893 outlines, although the legal right for women to stand for parliamentary election was encompassed in the wider campaign for womens suffrage, it was generally considered a political expediency that could be, and was, sacrificed for the greater goal of the franchise.

Once womens suffrage was achieved, the immediate priority was the upcoming general election and ensuring as many women as possible exercised their right to vote. Murmurings in some quarters of women increasing their political influence through direct representation in Parliament caught the ear of receptive male politicians. Over the next three years Alfred Newman and George Russell each presented bills to the House that aimed to remove womens political disabilities and admit women to Parliament. Women who had been active in the suffrage campaign made use of their extensive networks to garner support for these bills, and many small-scale petitions were sent to Parliament to validate womens demand for greater parliamentary rights. Some Mori women went a step further: they organised a hui and formed their own parliament for Mori women.

Next page