No, it isnt home neglecting

If you spend your time selecting

Seven blouses and a jacket and a hat;

Or to give your day to paying

Needless visits, or to playing

Auction bridge. What critic could object to that?

But to spend two precious hours

At a lecture! Oh, my powers!

The house is all a woman needs to learn;

And an hour, or a quarter,

Spent on voting! Why my daughter,

The home would not be there on your return.

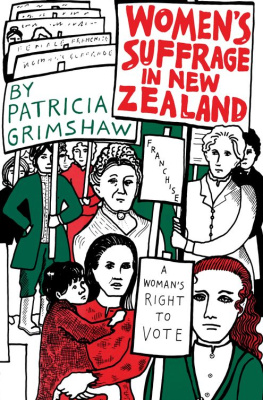

Suffragist verse, quoted in Patricia Grimshaw,

Womens suffrage in New Zealand, p. 74.

O n 19 September 1893 New Zealand women won the vote. We were the first country in the world where women could vote in parliamentary elections. I think that is worth repeatingwe were the first country in the world to grant women the right to vote in national elections.

It is an accomplishment of which to be proud. It was the result of a lengthy campaign by a number of determined women and men who used a range of methods to interest the public and politicians in the issue, and then build support in the House of Representatives and in wider society.

When I was studying History in the Fifth Formand that term, and the fact that I do not know what the modern equivalent is, dates meI loved it. Such interesting stories about the Russian and Chinese revolutions that helped me understand why events were happening in the contemporary world. Then we moved to the New Zealand part of the course and it was like walking in sticky mud. It was so dull. I cannot remember exactly what the topic was, but it involved learning about various pieces of legislation. It was quite possibly about the social reform legislation introduced by the Liberal government of the 1890s and early 1900sof which womens suffrage was a part. I remember thinking that I would do anything rather than study New Zealand history. Other countries history was interesting; New Zealands was dull.

Since then, I have learnt a lot about New Zealand history, and have completely changed my mind. What a fascinating history we have. And the story of the campaign to get votes for women is a great example. We have heroines (Kate Sheppard), we have villains (Richard Seddon and Henry Fish); we have drama as electoral bills are introduced into parliament, only to fall at the last hurdle; we have women making an appearance in the public life of New Zealand, many for the first time; and we have success, snatched from the jaws of defeat.

And then, after struggling for the right to vote for so long, women were able to exercise that right just two months later. How exciting must that have been?

One of the questions I asked myself when I began this book was whether another book on the fight for the franchise was necessary. When we celebrated the centenary in 1993, historians around the country produced all sorts of publications. Some of them were general histories of the campaign, some were focused on a particular area, some were collections of biographies of women. All of these books, large and small, uncovered hidden stories of womens activities at the time. What more needed to be said, I wondered. Then I realised that not only was the centenary over fifteen years ago, but there were different ways of looking at the campaign.

The first three chapters of this book are a history of how the vote was won. The second part of the book is a series of biographies of some of the well-known and less well-known women, and a few men, who were significant in the story of the franchise in New Zealand.

I have taken the opportunity in the third chapter to write at length about the election campaign and election day, 28 November 1893, because of its uniqueness. Never before had women voted in a general election, and as a result there was a considerable amount of newspaper coverage. I also felt that it would be interesting to write about what those extraordinary women who had expended so much time and energy during the suffrage campaign did next. Did they collapse, exhausted, and vow never to do such a thing again, or did they continue their work to extend the rights of women? As it turned out, they did both, but the women I have written about in this book mostly continued their public work for the extension of womens rights. I have included Kate Sheppardher contribution could not be overlookedand others whose names may be less familiar, such as Marion Hatton from Dunedin, and Annie Schnackenberg from Auckland.

I thought, too, that the role of some of the male politicians needed to be acknowledged. If it had not been for men such as Sir John Hall and Sir Robert Stout who introduced bills to parliament which included womens suffrage, the measure could not have passed. Women may have been the prime movers in the campaign but, practically, it needed men to make it happen.

Similarly, I wanted to show that the ability to vote was just the first step. Women wanted to be able to stand for parliament as well, but that did not happen until 1919. I decided that I would include a chapter on the first three women who stood that yearAileen Cooke, Rosetta Baume and Ellen Melville. Except for Ellen Melville, whose name is familiar to Aucklanders, these women are now forgotten. And then I realised that I needed to include a chapter on the first woman to be elected, Elizabeth McCombs.

They are all remarkable people. Behind them, helping and supporting, making sure that letters were written and signatures were collected for the suffrage petitions, there were innumerable other women whom we know little about. I have tried to mention some of these as we go along. Many of them were rural women, whose activities were noted in many of the local suffrage histories produced in 1993. There were also Maori women, such as Meri Te Tai Mangakahia, but her focus was on the Kotahitanga parliament, and she does not seem to have been involved in the general campaign. I hope that when you read the biographies in this book, you will also think of those innumerable nameless women. I remember my own surprise and pride when I discovered that some of my Hutching relatives from Woodville had signed the suffrage petition. The discovery immediately connected me to the campaign in a very personal way.

We have witnessed an enormous arc of progress since 19 September 1893. It took a long time for women to be given the right to stand for parliament, and many years before one was elected. The number of women members of parliament (MPs) was small, and it was not until the introduction of mixed member proportional (MMP) representation in 1996 that the numbers began to increase. They still do not reflect the proportion of women in the population. Stillwe have had some significant achievements in the past 16 years since the suffrage centenarytwo women prime ministers, two women governors general and a woman as the chief justice.

In some ways we take those achievements for granted, in the way that we take the presence of Kate Sheppard on our ten-dollar note for granted. But reported comments about the women who hold prominent public positions, which concentrate on their gender rather than their abilities, make us realise that we still have a way to go before women and men have equal rights in the way that Kate Sheppard and her sister suffragists desired.

I hope this book convinces you, too, that New Zealand history is exciting and interesting, and tells us great stories about ourselves and why we are the people and society we have become.

A note about terms and definitions: I have used the words suffrage, franchise and the vote interchangeably in this brief history. The first two mean the samethe right of voting in political electionsand the third is shorthand for the same thing. I have mostly not used women or female, assuming that is taken for granted in a book about womens suffrage.