For many people a speech is something to endure before the main eventthe entre, if you like, before the main course.

Good speeches, however, can be the centrepiece. They are documents of a place and time; they encourage and they inspire. Truly great speeches can change the course of history.

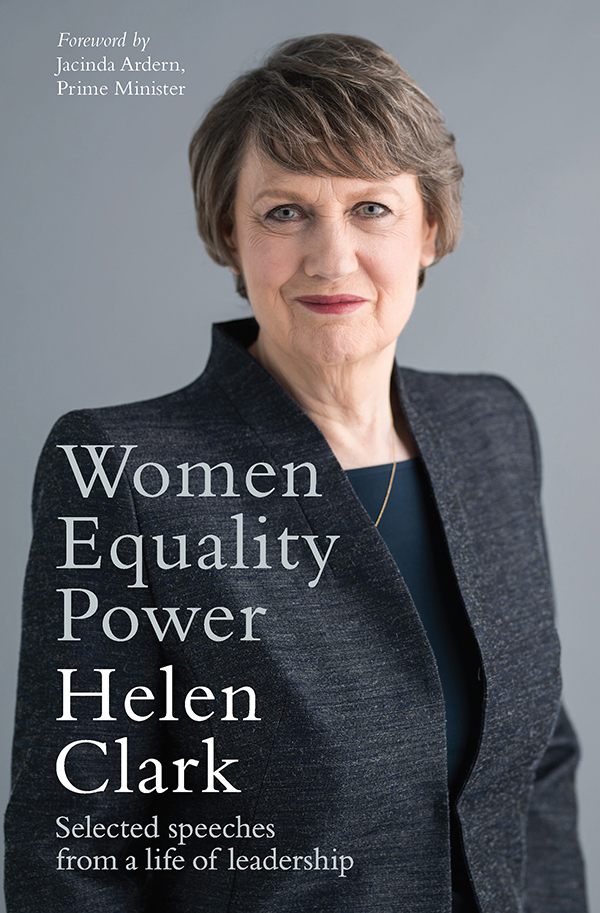

Helen Clark put New Zealand on the world stage. Always the pragmatist, she was never afraid to say what she thought. That sometimes worked against her, but more often than not it garnered admiration and respect.

She often said, and continues to say, that having women in leadership positions not only sends a powerful message to other women but also changes societies perceptions of gender roles and encourages girls to believe that no door is closed to them.

In many ways Helen opened the door for me. My generation grew up under her leadership. I was lucky enough to get a job in her office not long after I left university. Helen was wise, inspiring and provocative; she remains so to this day.

In 2008, in a speech to parliament, Helen said she was motivated by one goal: to secure the best possible living standards for all New Zealanders. Her vision of a sustainable and prosperous country, where inclusion and partnership was a given, is an enduring one.

I remember Helen saying in her valedictory speech (see minister, because the politicians of that era were invariably elderly men.

When Helen entered parliament there was still such a thing as a gentlemens club: the Members lounge, where a billiard table was dominated by be-suited blokes. There were eight women MPs.

By the time she left parliament there were 40 women MPs. Helen broke the mould, and there is no doubt in my mind that she laid the path that I have benefited from.

Its pertinent here to reference a line in the speech I gave at the launch of the 2017 election campaign about how easy it is for leaders to come and go, but its the really good leaders who leave something good behind.

Helen has certainly done that.

I hope you enjoy the book.

June 2018

It is 2018, and around Aotearoa New Zealand, women are celebrating the 125th anniversary of winning the right to vote for all women, Mori and Pkeh alike. In 2019, we will commemorate several other milestones of significance. It will be one hundred years since New Zealand women won the right to stand for parliament. It will also be 20 years since we witnessed Helen Clark win the 1999 election to become New Zealands first female Labour prime minister, and ten years since Clark became the first female head of the United Nations Development Programme (in 2009).

These moments in history are a result of the collective achievements of generations of women and the determination of individual women. And although New Zealand can claim three female prime ministers, negotiating the path to the pinnacle of political leadership remains a rare feat for women, both here and around the world.

Perhaps as a result, there continues to be considerable public fascination with the women who achieve these roles. They are seen as exceptional rather than the norm. Their popularity is sometimes greeted with astonishment, and their unpopularity is propagated as a reason why women should not be given the highest national office. This is never an extrapolation made about poorly performing men.

The rarity of seeing women in high office means that biographies and published interviews provide the public and scholars with invaluable insights into what is required by these remarkable women. This book is no exception. The selection of speeches given by Clark in parliament as an MP, cabinet minister and prime minister, and in her post-political career, highlights the range of issues she has championed for New Zealanders, for our region, and for women globally.

Clark recognises the significance of the Labour Partys long history in her maiden speech. Established in 1916, there has been no shortage of significant leaders of the Labour Party, including Michael J Savage. But also of note is that the partys first executive included two women, one of whom was Elizabeth McCombs, who went on to become the first woman elected to New Zealands parliament in 1933. From the outset, Labour Party women demanded a voice, and the opportunity to organise separately, in ways that went beyond the traditional auxiliary function. Women-only branches were established throughout the country and these proved critical to the advancement of Labour women and their policy interests.

Indeed, in addition to the civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam war protests, the womens liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s resonated with many Labour women. They established the Labour Womens Council, and sought to revitalise what some thought was an elderly, male-dominated, conservative and sclerotic organisation. Labour women, including Clark who joined the Party in 1972, were critical to the process of party reform that heralded a more diverse cohort of candidates, parliamentarians and policies of economic and social equality.

Up until this point, womens representation in the New Zealand parliament had been tokenistic at best. In the period between 1933 and 1946, only six women were elected, four of whom were Labour MPs. This trend of Labour proving the party more amenable to womens representation continued and, in 1981, the year that Helen Clark was elected for the first time, the percentage of women elected doubledfrom 4.3 per cent to 8.7 per cent. As Clark herself says, this was a meaningful moment for womens representation, with her and two other new Labour women elected, doubling Labours womens caucus from three to six. The advance of Labour women into parliament continued, a direct result of Labour womens activism, and the proportion of women in parliament reached 21 per cent by 1996. This comparatively high percentage was considered a most unusual feat in political systems without proportional representation or gender quotas.

Research tells us that building a political career and winning the

However, we also know that political institutions are not gender neutral. There are gendered codes that underpin the practice and processes of candidate selection, campaigns, legislative work, cabinet careers and attaining executive leadership. Gender matters because in politics, as in other professions and walks of life, dominant cultural codes of masculinity and femininity persist. These order behaviour and attitudes in relation to the accepted rules of the game and what is deemed an acceptable career pathway in politics. Once these rules and norms become institutionalised, political actorswomen and menlearn them, invest in them and make decisions accordingly.

We gain a glimpse through Clarks words of how she has managed to negotiate these (gendered) career requirements. Clark won the safe seat of Mt Albert in 1981, but only after running for local government (twice) and for the rural seat of Piako. She undertook considerable executive service for the Labour Party, and worked in a range of committees and portfolios, in government and in opposition. Thus, by embracing a wide range of parliamentary experiences, Clark ensured she was ready for a ministerial position.

Although she never held the Womens Affairs portfolio, Clarks consciousness of the importance of womens issues was raised early in her tenure as a parliamentarian. First, women in the community regularly raised their issues with her because she was a woman MP and, as a result, she came to see acting for women as a necessary part of the job. When I came here [the women in parliament] did feel there was a womens constituency that was genuinely underrepresented. Once you got the opportunity to be a Minister you set about righting a few wrongs of long standing.