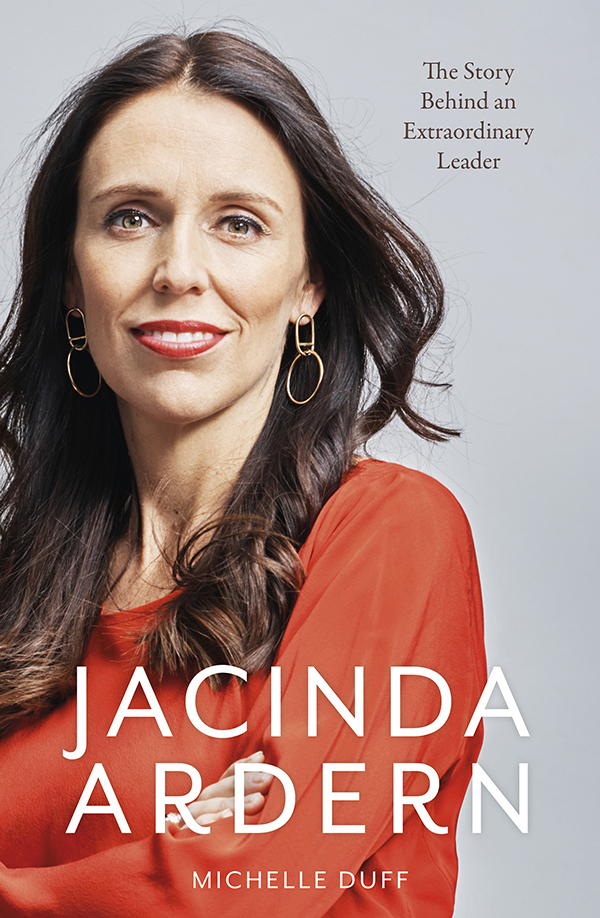

First published in 2019

Text Michelle Duff, 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Allen & Unwin

Level 3, 228 Queen Street

Auckland 1010, New Zealand

Phone: (64 9) 377 3800

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.co.nz

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

ISBN 978 1 98854 716 9

eISBN 978 1 76087 321 9

Design by Kate Barraclough

Cover photograph: Charles Howells

Cover design: Kate Barraclough

FOR MY PARENTS,

KATHLEEN AND NED DUFF

MOST PEOPLE WHO ARE OLD enough to recall will be able to tell you what they were doing when they found out Princess Diana died, or where they were during the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York. I will never forget walking into a deathly silent newsroom in Wellington moments after the devastating February 2011 Christchurch earthquake had struck, the laughter Id been sharing with my lunch buddies drying up as we took in the pain and terror playing out in real time on screens before us. A mans beard coated in dust, his eyes like a trapped deer. Buildings reduced to rubble. When I tried to call someone for a scheduled interview about another story, I couldnt get the words out. All else had been rendered inconsequential.

Theres a name for these sorts of memories, the ones you retain of how you experienced a momentous historical event: theyre called flashbulb memories. In 1977, Harvard psychologists Roger Brown and James Kulik wrote that these types of memories were formed during surprising, consequential and emotionally affecting moments, with some people having an almost photographic recall of the circumstances surrounding the occasion. A personal or cultural connection to a dramatic event, and the sense that it will change things, will heighten the likelihood of it being remembered.

JACINDA ARDERN BECAME THE PRIME MINISTER of New Zealand on 26 October 2017. Just a couple of months prior she hadnt even been in the running for the post but, seven weeks out from a general election, she was given the job of resuscitating the flailing Labour party. Not only did she pull it from the depths and freestyle it to a place where victory was possible, she then negotiated a coalition deal with one of the countrys wiliest politicians. Ardern, who was set to become the worlds youngest female leader, was putting together the sixth Labour Government while others were still catching their breath.

For many, watching the ascendance of a politician who spoke of kindness, inclusivity and social justice, who offered an alternative path to the one wed been trudging for the past nine years, felt exciting enough. The fact that she was also a young woman who had pledged her commitment to gender equality while speaking of solutions to climate change, child poverty and sexual and domestic violence made it seem as though change might actually be possible. Arderns slogan going into the election was relentlessly positive, and her star power proved contagious.

Her election win was a phenomenal achievement for any politician. But there were more surprises to come.

Arderns pregnancy came as a surprise to both her and the nation, and news of it was mainly received with joy. But why did it feel so meaningful?

Just a few short months later, in January 2018, Ardern announced she hadnt just been fighting to win on the campaign trailshed also been battling fatigue and morning sickness, and was due to give birth in June. She would be the first prime minister in history to take maternity leave and the second ever to have a baby while holding a nations highest office, behind Pakistans Benazir Bhutto in 1990. Clarke Gayford, Arderns partner, would be a stay-at-home dad.

Arderns pregnancy came as a surprise to both her and the nation, and news of it was mainly received with joy. But why did it feel so meaningful? Babies are born every day, and plenty of parents have to manage them with careersbut we dont often hear about men juggling their jobs with their children. For the most part, in those families that follow the nuclear model, its still expected that men will be the breadwinners in a household, while women are the primary caregivers. Even when those roles are switched, studies have shown that childcare and domestic duties are not shared equallywomen can still find themselves carrying the bulk of the household chores and family administration, while feeling guilty about not doing more.

From before babies are born, we assign them roles, personality traits and even colours depending on their expected sexwhich we assume tells us their gender. Blue is for boys. Pink is for girls. Why dont you cut his hair? Should she really be climbing that tree? Young women soon realise there are restrictions on their behaviour that dont exist for boys. Too confident, and theyre bossy. Too passionate, and theyre hysterical. Also, dont laugh so loudits not ladylike. Close your legs. Be nice. Why dont you smile more?

It says a lot about where were at as a society that it is still considered groundbreaking and inspirational for a high-profile leader like Ardern to combine motherhood and political office.

By the time women reach adulthood, we know the limits so well were setting them ourselves. Yes, you can take that new job but only if you figure out how to manage it around childcare. And are you sure your kids wont be irreparably damaged if youre not at home to make them afternoon tea until theyre 72? Of course you love that skirt but maybe its just not appropriate for a woman your age. No, you dont want to spend so many mind-numbing hours every year removing so much of your body hair but can you really stand the sideways looks youll get at your un-depilated armpit?

It says a lot about where were at as a society that it is still considered groundbreaking and inspirational for a high-profile leader like Ardern to combine motherhood and political office. And yet we are so unused to associating pregnancy with power that Arderns example is both. Gayford as the primary caregiver, snapped while out with the pram or dangling cuddly toys in the background of formal events, is also blazing a trail thats impossible to ignore. In occupying such non-stereotypical roles, they are both refuting the idea that ambition and nurturing are gendered or even oppositional traits.

Its not like theres an omnipresent being telling us all what to dobut the pull of traditional societal expectations is strong. They shape us in myriad ways that we often dont even notice. Every day, pressure to conform comes both externally (from the media, and comments made by friends and family) and internally (from the ingrained ways we have been taught to behave throughout our lives). In truth, it makes about as much sense to assign someone inherent traits based on their gender as it does to assume a person knows karate because theyre from Japan. Yet we still do it, to ourselves and to others. Having very visible examples such as Ardern and Gayford pushing back against these norms creates more room for all of us to live our lives.

ON 15 MARCH 2019, LIFE as we knew it in this country changed forever. The terror attacks on Al Noor and Linwood mosques in Christchurch saw the lives of 51 Kiwi Muslims ripped away, and about 50 injured. Those who did survive will face years of surgeries and rehabilitation, while families and communities have been left shattered. We didnt think we would ever see such an act of hatred and destruction here. Until we did.