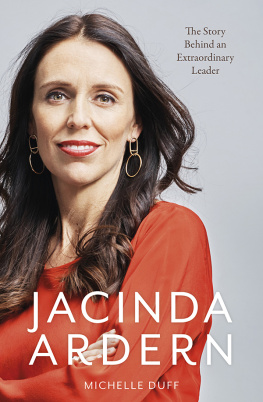

Published by Nero,

an imprint of Schwartz Books Pty Ltd

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

www.nerobooks.com

Copyright Madeleine Chapman 2020

Madeleine Chapman asserts her right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

9781760641818 (paperback)

9781743821312 (ebook)

Cover design by Akiko Chan

Text design and typesetting by Marilyn de Castro

Internal images reproduced courtesy of: Yearbook photos, both Morrinsville College; Young Labour bus photo, Kent Blechynden / Stuff / Dominion Post; Maiden speech, Ross Giblin / Stuff / Dominion Post; Ardern and Gayford at a bar, Carmen Bird Photography; DJing at Laneway Festival, Fiona Goodall / Stringer / Getty; First press conference photos, Embracing a mourner, all Hagen Hopkins / Stringer / Getty; Clark and Ardern, Stuff / Dominion Post; Ardern and Gayford at Buckingham Palace, Neves birth announcement, both AAP; ArdernGayford family at the UN, Don Emmert / Getty; Ardern mourning mosque attacks, Kirk Hargreaves / Christchurch City Council

For Uncle Fata,

who would have been the first to read this and the first to brag about it. Sooole.

PROLOGUE

19 October 2017

J acinda Ardern did not want to be prime minister. Ive seen how hard it is to raise a family in that role, she explained in 2014. A year later, she stated it more bluntly: I dont want to be prime minister. Whether this was simply a party line or a more firmly held personal one, it sounded convincing.

So perhaps it surprised Ardern, more than anyone else, that on a bright, spring afternoon in 2017 she was waiting to find out if she would become Prime Minister of New Zealand.

Her political ascent had been steady then rapid. First elected in 2008, she was at the time the youngest sitting MP. Just nine years later she was the leader of the opposition. At the start of 2017 Ardern had still seemed like a team player with a long career ahead of her. Then a fellow MP resigned and she took over his seat. Two weeks later the deputy leader stepped down and she took over from her. A mere five months after that, when the party leader resigned, Ardern stepped up and took the job one she claimed shed never wanted.

At that point she had just seven weeks to turn around Labours terrible polling and win the election. Her debut speech as leader led to a surge in support for the party and with a campaign featuring an open commitment to action on climate change and a lot of Facebook Live videos, Ardern lifted the Labour Party from their worst polling in decades to winning enough votes to potentially form a government.

But to do so they had to form a coalition and that meant negotiating with New Zealand First, who held nine seats. Winston Peters, the leader of New Zealand First, in the role of kingmaker for the third time in his political career, had spent several weeks in negotiations with both Labour and National (who had won more votes but still needed his party in order to govern). If he chose to go with Labour and their fellow left Green Party, theyd form a coalition minority government. But when he stepped up to the microphone Labour still had no idea which way his vote would go. Peters had played his cards close to his chest.

Surrounded by staff in her office, Ardern watched her television like everyone else as Peters addressed the nation, describing his difficulty in making the decision. He was the political Bachelor, idly twirling his final rose.

When he finally announced that hed chosen Labour, Arderns office erupted. A bottle of whisky was opened and Ardern poured for everyone except herself.

Her morning sickness hadnt kicked in yet, but it would. Just six days earlier, three weeks after the election and in the middle of negotiations with New Zealand First Ardern had found out she was pregnant with her first child. Shed be combining parenthood with political high office after all.

After nine years of saying she didnt want to be in charge and seven weeks of saying she did, 37-year-old Jacinda Ardern became the fortieth prime minister of New Zealand.

FROM MURUPARA TO MORRINSVILLE

T he photograph from 1985 shows two smiling girls in a trailer with a dozen other neighbourhood kids. One of the girls has light blonde hair, the other brown. They sport impressive mullets and are the only white faces in the group.

Jacinda Ardern and her older sister, Louise, grew up in Murupara, a small forestry town in the middle of New Zealands North Island. The population of 2000 was overwhelmingly indigenous, so the girls schoolmates were predominantly Mori.

Jacinda Kate Laurell Ardern was born on 26 July 1980 in Hamilton, but her first memories were formed here, in Murupara, where the family moved when Jacinda was five. Her father, Ross, was posted there as a police officer. Murupara was a tough area. The Tribesmen a newly formed motorcycle gang ran the town, and the privatisation of the forestry industry had seen many locals end up on the dole. The Arderns lived in front of the police station, and Jacinda witnessed no shortage of poverty and violence in her time there. Jacinda has said her early childhood shaped her as a politician. If its possible to begin building your social conscience when you are a small child, she said, then that is what happened to me.

Of course, as a five-year-old, Jacinda didnt see kids without shoes and think of the privatisation of primary industries and the collapse of central government. She just saw kids without shoes and thought it was unfair. I never viewed the world through the lens of politics then, and in many ways still dont, she would later say. Instead, I try to view it through the lens of children, people, and the most basic concept of fairness.

As a child, Jacinda was relatively insulated from the injustice around her in Murupara. Her family were financially better off than most of their neighbours. But as Ross was a police officer, some of the locals werent fans of the family. Bottles were thrown at the Arderns house, and altercations occurred outside the station.

One day, Jacinda ventured out the back gate to walk to the shops and stumbled upon her dad surrounded by a group of men who clearly werent happy. Ross was talking to them calmly, trying to deescalate the situation. He spotted Jacinda, frozen on the spot. Run along, Jacinda. Its all right, he told her, before turning his attention back to the men. It was just a moment, but his approach to conflict stayed with her. Years later, as an MP, Jacinda would be known for her diplomacy when dealing with colleagues and opponents alike.

Although Jacindas family moved away from Murupara when she was eight, she has strong memories of her time there. The many, many jobs lost. The neighbour who died and who she later learned had committed suicide. The babysitter who turned yellow one day from hepatitis and didnt babysit anymore. It wasnt political, it was just unfair.

IN 1987, JACINDAS PARENTS ANNOUNCED the family was moving. To the big city? No, to Morrinsville.

Morrinsville wasnt a metropolis, but it was bigger and broader than Murupara more of a microcosm of the country as a whole, with wealth and poverty close neighbours. Families that owned large, successful dairy farms lived around the corner from recently arrived refugees. The largest, fanciest establishment was the Morrinsville Golf Club, which shared a border with the Ardern family home. The house a Lockwood design, constructed without nails had been built by Jacindas grandfather.