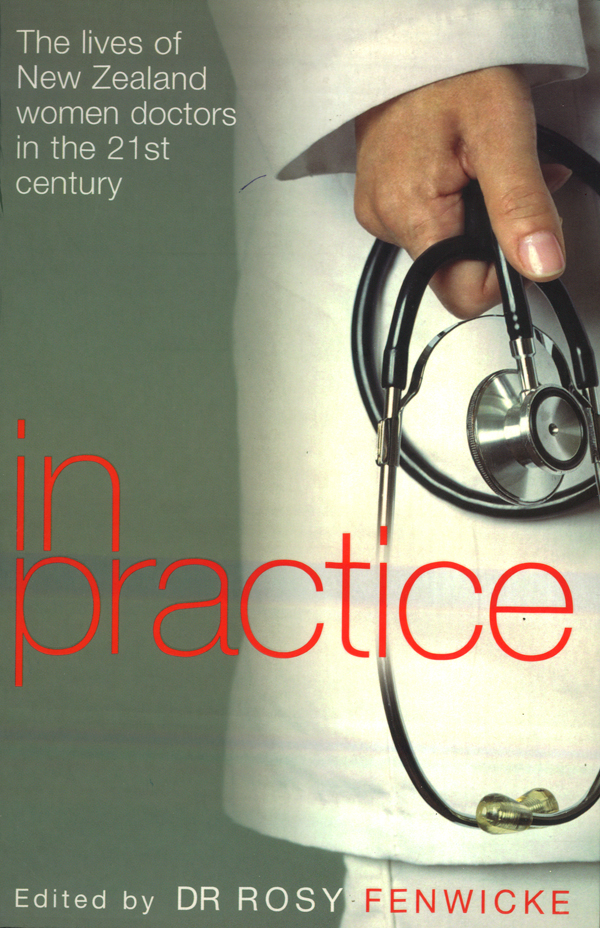

A new wave of female medical students trained in the 1970s and entered a profession previously dominated by men. These women have now made their mark in various fields of medicine. In this thought-provoking book, editor Dr Rosy Fenwicke asks: How do these women combine their professional and personal lives? What influence have they had in the health arena?

Among the thirteen women doctors sharing their stories are pioneering breast physician Jackie Blue; Helen Rodenburg, former president of the Royal New Zealand College of General Practice; Ruth Highet, sports physician and Olympic team doctor; gynaecologist Hilary Liddell; Robyn Toomath, endocrinologist and anti-obesity campaigner; and Papaarangi Reid, director of the Eru Pmare Mori Public Health Unit.

All royalties from the sale of this book will go to the establishment of a fund at Otago University which will give financial assistance to women medical students.

Dr Rosy Fenwicke is a GP with an interest in womens health and occupational medicine. As well as compiling this book, she is also profiled in it.

Introduction

T he idea for this book arose from a conversation among friends one Sunday afternoon, in November 2002. There were five of us three women, and two men. It was a spur-of-the-moment gathering. We hadnt spent time together in over a year. After the social niceties, the enquiries after children, family, homes and work, and after the second glass of wine, the discussion turned to the future and, by extension, its relationship to our present and past. We knew we were lucky people but we were all too busy. We had friends, families and interesting and challenging jobs, and we were all tired. We all had doubts about how well we were coping with the demands of everyday life. None of us had time for reflection. We were just running to keep up. Somehow, this daily reality seemed a long way from the dreams of our youth.

We talked of the idealism of our early years, and our plans to change the world for the better. We had set out to do great and marvellous things and oh, how easy it had all seemed then. We discussed the early and earnest attempts to change the social order we had inherited from our parents and the resultant battles won, lost and left to others to fight on our behalf. And as often happens when three highly verbal women get talking, we three took over the conversation, and talked of the change we had seen and experienced as women in the last 30 years.

Had feminism the concept that so radicalised the 1970s that young women now dare not speak its name helped or hindered us? Had we, in turn, been the true champions of womens rights and sexual equality we had set out to be? Had we lived the rallying cry of the second wave of feminism and made the personal the political? Or had we as ordinary women, albeit professional women, succumbed to the same pressures of family, finances, holidays, housework, relationships and work that make up so much of every womans daily life? Had we forsaken the cause and just got on with our own desires and needs, and been passively swept along by the times? Had we even been realistic to believe that people can make any difference to society, in its broadest sense, by the way lives are lived?

Later I thought of the young women I had known back then. Women who had entered medical school in the mid-70s, trained to be doctors, and who now worked throughout New Zealand in various fields of medicine. How did these women combine their professional and personal lives over the years of change? What changes had they precipitated by being women in a profession totally dominated by men until the 70s?

Over the next few days I phoned 15 or so women and with little hesitation almost all agreed to write about their lives and careers and have their work contribute to this book and help establish the Women Doctors Fund at the University of Otago.

Funded from the proceeds of the sale of this book, with donations welcomed, the Legacy Women Doctors Fund has been set up to award a yearly grant to a third-year female medical student studying at Otago Medical School. This is one way we can support and possibly encourage the next generation of women coming through what, at times, can seem a heartless, demanding and now costly system of training.

The contributors to this book, currently practising women doctors, inherited the legacy of free education from the work of previous generations. We are the lucky generation, the tail end of the generation known as the baby boomers. We grew up in a land of plenty, well past the years of Depression and war and just before the impact of Britain joining the Common Market and the oil shocks forced a change in the way New Zealand managed its economy, with consequent change in social policy.

Education in the mid-70s, and in particular tertiary education, cost the individual student and their family almost nothing except time. Our bursaries covered our university fees, and living was cheap. Holiday jobs were easy to get and earned us enough money to get us through the university year fed, clothed and entertained. Any financial contribution made by our parents was entirely voluntary and in fact minimal in the greater scheme of things. When we left university, unencumbered by anything except respected degrees, we were almost certainly assured of choice not only in where we would work, but also in how our careers could develop. The future was full of exciting possibilities, both in New Zealand and anywhere else in the world we chose to go.