Foreword

Shonagh Kenderine

Former Environment Court Judge

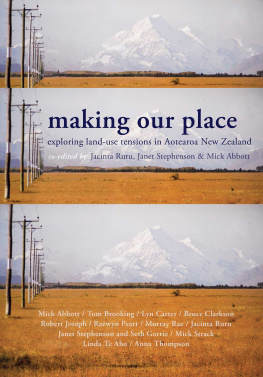

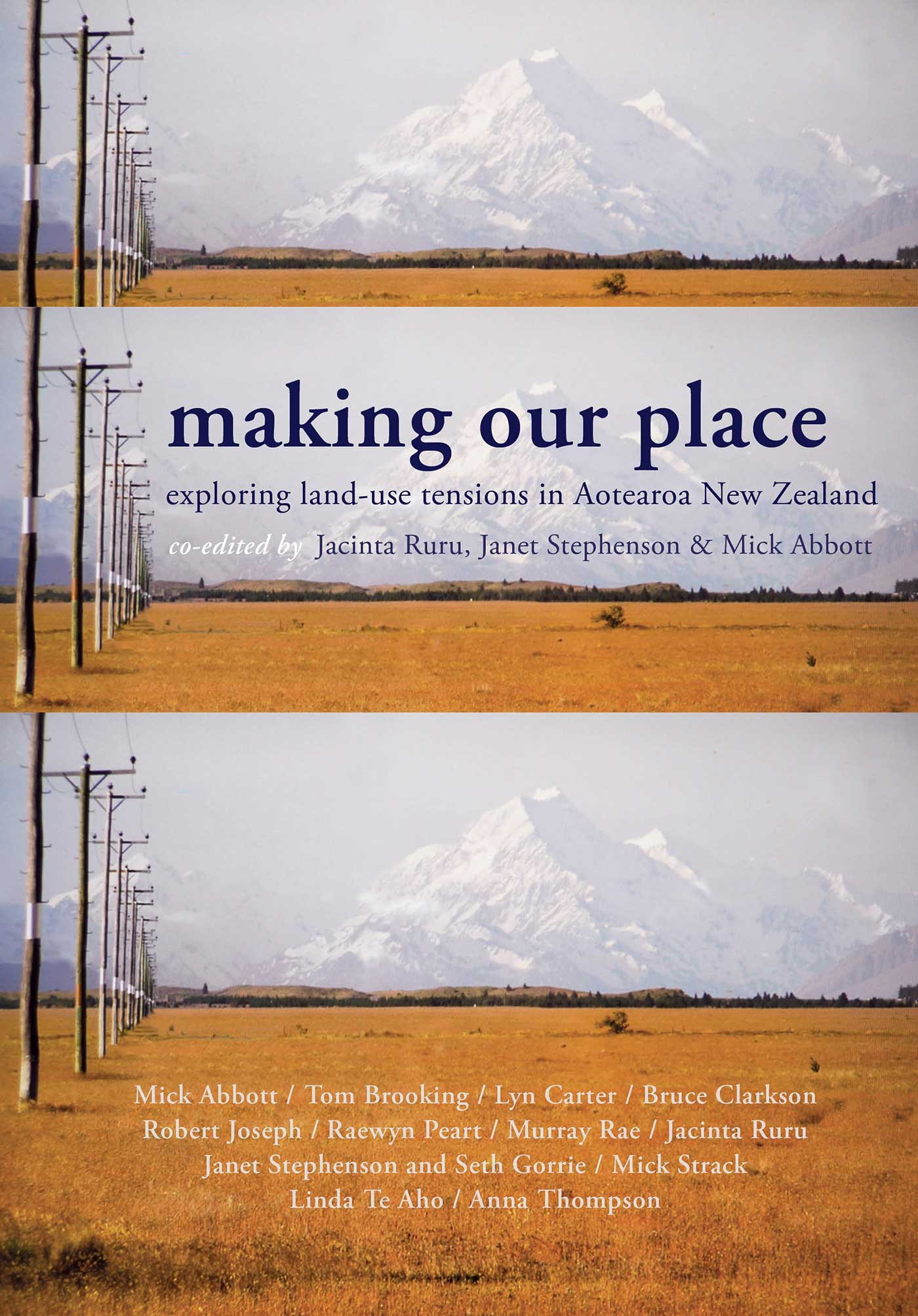

Making our Place offers fresh perspectives on the tensions and transformations inherent in the ongoing development of our natural and physical resources. The stories told will be infinitely readable for New Zealanders who are passionate about their place in these extraordinary islands at the bottom of the world. This lively and imaginative book will raise public awareness of our need to better engage not only with each other, but also with the lands and seascapes that shape us. The stories navigate where, as a nation, we have come from, what has transformed us both socially and economically, and the ways we negotiate the inherent contradictions of protecting valued resources alongside the need for development.

Some of the stories are startling in their implications, such as the dairying expansion planned for the iconic landscapes of the Mackenzie Basin. Other essayists explore with fresh eyes the new systems of governance emerging out of recent legislation, Treaty of Waitangi settlements and co-management arrangements. A succinct resum of the legislative history and political responses to the customary ownership by Mori of the seabed and foreshore traces one such journey. Another essay outlines the importance of the Waikato River to the Waikato-Tainui peoples, and the co-governance arrangement made possible by Treaty settlement. While these journeys have been difficult, both essayists conclude with a sense of optimism.

The inappropriate development of the nations treasured coastal landscapes is explored in an illuminating case-study of the Tutukk coast. The region has a history of failed landscape protection efforts by communities and organisations, and the author puts forward a creative proposal for Heritage Coasts. The value of place names in New Zealand culture is explored in an elegant piece in which the author examines the way in which the two cultures have bestowed, ignored, adapted or adopted place names. The author details the origins and resolution of the Wanganui versus Whanganui debate, and explores the wider significance of naming.

Three insightful accounts discuss the impact of colonial and post-colonial settlement. One explores how the work of the early European surveyors disrupted forever the values, needs and expectations of Mori landowners. Another essay discusses the background of those who came from England, Scotland and Ireland to settle on the land made ready by the surveyors. A third traces the ecological transformation of Taranakis original landscape from a unique reservoir of indigenous biodiversity, to the devastating impacts of human settlement, to recent initiatives to protect and restore ecosystems. All of these themes fundamentally shaped, and continue to shape, the rural landscapes of today.

Wind farms and other renewable energy projects will become increasingly part of future landscapes yet their impacts on landscapes are contentious. This essay suggests that more explicit identification by both cultures of their values in landscapes is urgently required, and that communities should be engaged before development processes begin. Conflicts have also been far too common between development and protection of sacred Mori sites, and this essay offers a timely analysis as to what is and is not a whi tapu. It ends with optimism for the future of whi tapu through the emergence of a legal system that recognises both European and Mori values.

There are strong links between our architectural history and its symbolism in the landscape. Using Auckland as an example, one chapter explores the built structures on the citys high points, all of which are reflective of significant stories in our development as a nation. Another imaginative essay explores, with instructive photographs, ways communities can better interact with the public conservation estate so they can become more intimately engaged with them.

In the final essay, the co-editors suggest ways forward which may lessen conflict and enhance mutually nurturing relationships between people and place. This book peels back layers of misinformation around many of our most difficult land-use tensions. It provides a timely platform for greater understanding of the relationships between people and our environment, and suggests innovative ways to reduce these tensions so that we can more peacefully make our place together.

introduction

chapter 1

Tension lines

Jacinta Ruru, Janet Stephenson,

Mick Abbott

Aotearoa New Zealand is a land apart, a series of islands located in a remote corner of the Southern Pacific. Its economy has been built on both natural resources that support export-oriented agriculture and other primary industries, and spectacular lands that entice international tourists. But can land-use changes such as coastal development, energy infrastructure and dairy farming be reconciled with retention of highly valued landscapes? How should a balance be struck when beauty and industry are both vital to the countrys economic wealth? Moreover, what happens when another dimension is at play the claims of indigenous peoples for a share in governance over resources in a country that prides itself on being a world leader in race relations? And, just as contentious, how are we to grapple with twenty-first century realities of urban and coastal development and new technologies, such as large-scale wind farms, on arguably sacred or fragile landscapes?

Despite the apparent diversity, all of these issues have one thing in common each altercation is played out in a specific place about which people feel passionate, albeit for diverse reasons. Our fascination with the interplay of people, place and contestation inspired us to bring together a group of New Zealanders from different backgrounds and disciplines to explore some of the stories and sites of conflict found along our coastlines and rivers, in our forests and tussock uplands, and amongst our sacred, historic, rural and urban landscapes. The nuances of the sites and conflict differ in each, but all engage with the underlying question of this book: are there better ways to reconcile the tensions inherent in our struggles with the land and with each other in making this land our home?