Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site

30 Ramey Street, Collinsville

On the western edge of the Prairie State, where the Mississippi River cuts its way between Illinois and Missouri, a floodplain extends inland until stopped by a range of rocky bluffs, covered with loess (windblown silt). This productive area stretches seventy-five miles from where the Missouri River dumps its muddy water into the Mississippi near Alton southward to the Mississippis junction with the Kaskaskia River. Known as the Great American Bottom, it was shaped over time by the powerful force of the Mississippi.

But nine centuries after the Paleo culture and not far from present-day Collinsville, an extensive and vibrant prehistoric community flourished here. Those intriguing native people disappeared long ago, but the enduring signs of their presence are visible in dozens of mounds found throughout the twenty-two hundred acres of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, one of the most important pre-Columbian settlements north of Mexico.

The ancient peoples who eventually made their way into the Great American Bottom arrived on the North American continent from Asia thousands of years earlier. Some traveled across the Bering Land Bridge, which appeared when the sea level dropped as water froze into glaciers while others possibly crossed the Bering Strait by boat. Examinations by archeologists and anthropologists of stone-tool artifacts found on both sides of the Bering Strait have long indicated that these items were produced by people of the same culture. More recently, analysis of DNA extracted from the twelve-thousand-year-old remains of a young boy unearthed in 1968 on a Montana farm has provided further evidence that Paleo Indians originated in northeast Asia.

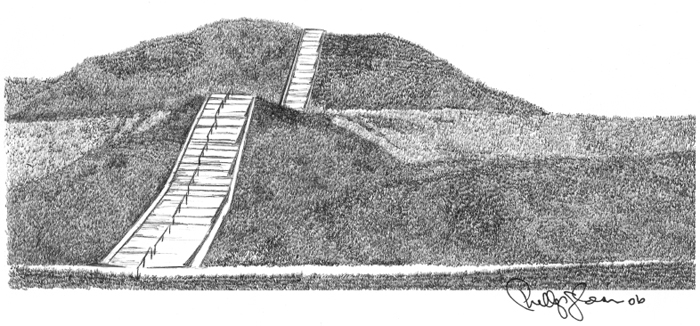

Monks Mound on ancient plaza, Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site. Illustration by Phil Glosser.

With the arrival of a warmer climate and the resulting changes in the regions vegetation and animal population, an Archaic Indian culture developed, existing between about 8000 to 600 BC. Archaic Indians in the Cahokia region, perhaps, were less nomadic, practiced a primitive form of agriculture, and constructed some of the first mounds here.

The next group who lived on the northern end of this region and who constructed the mounds were there mostly during a time known as the Mississippian cultural period. The Mississippian people built other mounds nearby: some where the city of East St. Louis is now located, some farther south, and others across the Mississippi River at present-day St. Louis. The many mounds at the Cahokia site indicate that it was the core of an extensive native culture found throughout much of the American Bottom.

Who Were the Cahokians?

Archeological study shows that the society at Cahokia was sophisticated and well structured, but it existed as a thriving community for only about three centuries. Then, for reasons yet unknown, it disappeared, and the people who lived here slipped into the haze of history. Although they left no written records, their former presence remains hauntingly visible in the impressive and fascinating complex of mounds, plazas, and other artifacts that give voice to a remarkable prehistoric society still not fully understood.

Archeologists and anthropologists have investigated Cahokia for decades, but many questions concerning its inhabitants and their social order remain unanswered. Those who have carefully dug into the sites mounds and examined the objects and other features revealed by their spades and trowels do not agree unanimously on several aspects of Cahokia. Still unclear are how many Cahokians lived here, the exact organization of their society, the nature of their religious beliefs, and the extent of their and Cahokias influence.

While it is known that a sizable number of native peoples established a broad-based and sophisticated community here between about AD 1000 and 1250, there is less certainty about how Cahokia was governed and structured. Some anthropologists theorize that Cahokias society was a hierarchically organized chiefdom, where upper-class chiefs and their subordinates occupied leadership positions, and workers from among the other people

Although it is clear that Cahokia grew over the years, views concerning exact developments in its history differ.

A Place of Mounds and Plazas

The tangible signs of this well-developed and complex ancient settlement are the mounds the Cahokians constructed. Seventy-two mounds of varying sizes and conditions are preserved at Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site. Around this plaza and at least three others, Cahokias residents carefully arranged their mounds, which vary in shapes and sizes. Some have flat tops; others are ridge-topped with sides that slant downward, rooflike.

Now grass covered, the mounds look almost lush, but this may very well not have been the case when the Mississippians were here. Some archeologists believe the mounds may then have been bare and that the residents worked as needed to keep them free of vegetation and to combat the erosion that must surely have resulted from such conditions.

A massive hill that in the summer stands green against the blue midwestern sky, Monks Mound emerges at the north end of the Grand Plaza. It is the largest prehistoric earthen mound found anywhere in North America.

Monks Mound is made up of four large tiers that climb finally to a flat top a hundred feet above the Grand Plaza.