THE LINCOLN-DOUGLAS DEBATES

Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas

Edited by Edwin Erle Sparks

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

MINEOLA, NEW YORK

DOVER THRIFT EDITIONS

GENERAL EDITOR: SUSAN L. RATTINER

EDITOR OF THIS VOLUME: STEPHANIE CASTILLO SAMOY

Copyright

Copyright 2018 by Dover Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2018, is an unabridged republication of the work originally printed in 1918 by F. A. Owen Publishing Company, Dansville, New York. A new introductory note has been specially prepared for this volume.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865, author. | Douglas, Stephen A. (Stephen Arnold), 18131861, author. | Sparks, Edwin Erle, 18601924, editor.

Title: The Lincoln-Douglas debates / Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas ; edited by Edwin Erle Sparks.

Description: Mineola, New York : Dover Publications, 2018. | Series: Dover thrift editions | Unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1918 by F. A. Owen Publishing Company, Dansville, New YorkBack of title page.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018001950| ISBN 9780486817231 (paperback) | ISBN 0486817237 (pbk)

Subjects: LCSH: Lincoln-Douglas Debates, Ill., 1858. | United StatesPolitics and government18571861. | Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Political career before 1861. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / Civil War Period (18501877). | LANGUAGE ARTS & DISCIPLINES / Rhetoric. | LANGUAGE ARTS & DISCIPLINES / Public Speaking. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Political Process / Elections. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / General.

Classification: LCC E457.4 .L535 2018 | DDC 973.6/8092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018001950

Manufactured in the United States by LSC Communications

81723701 2018

www.doverpublications.com

Contents

NOTE

It was 1858less than two hundred years agowhen two candidates went toe to toe for the opportunity to represent Illinois in the US Congress. One was six feet four inches, an attorney and a former state representative. The other was a foot shorter (maybe even more, according to some sources) and was the incumbent senator.

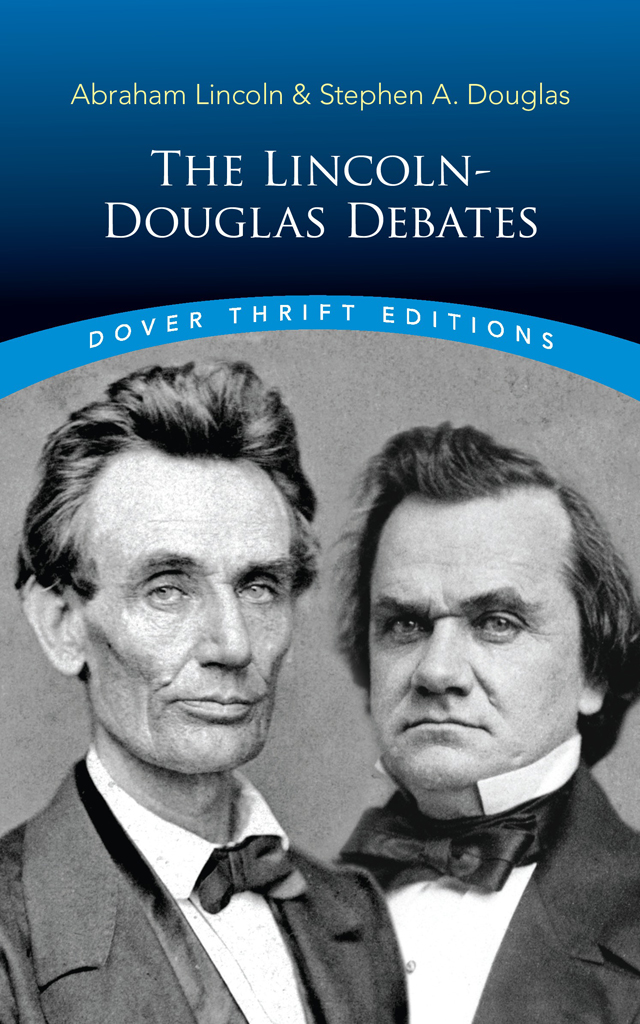

Abraham Lincoln, a member of the newly formed Republican Party, was a less seasoned and entrenched politician on the national scene than Stephen A. Douglas, who was known as the Little Giant because of his short stature yet forceful presence. Douglas was a favorite figure in the Democratic Party and gunning for the US presidency in the near future.

Douglas traveled by private train from town to town, campaigning for his reelection. Lincoln often immediately followed him, taking advantage of the huge crowds, and responded to folks questions about his opponents stances. Douglas finally agreed to add seven extra dates to his already full schedule so that the two men could appear in public together.

The results are in the history books: Lincoln won the popular vote, but Douglas won the legislative districts. Douglas was named US senator once again. However, the Lincoln-Douglas debates eventually catapulted the gangly gentleman, originally from Kentucky and Indiana, to the highest seat of government and to becoming one of the best-loved figures in US history.

INTRODUCTION

Stump SpeakingAs the American people pushed their way across the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific, the thin edge of advancing civilization was known as the frontier. It was made up of courageous spirits who subdued the Indians, drove the French and Spanish from their pathway, slew the wild beasts, felled the forests, built their log cabins, and planted their fields. Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett belonged to these hardy people. Cut off from the comforts and privileges which they had enjoyed before migrating to the West, these people resorted to various makeshifts to supply their needs. They used Indian moccasins on their feet, and coonskin caps on their heads. Lacking newspapers, they learned the issues of the political campaigns by assembling to hear the candidates who, in turn, mounted the stump of a felled tree in the streets of the frontier town and from that forum addressed the voters. A good stump speaker could always attract a crowd, and a wit combat between two speakers representing opposite parties was a real holiday of sport. It is true that the jokes and counter-strokes were often feeble attempts, and sometimes not very far removed from vulgarity; but the stronger the blows the better they were liked, and the more personal, the more enjoyable they were.

The spirit of democracy was strong in these pioneers and made them intensely interested in politics. Their fondness for hearing political speeches, their attendance upon political meetings, their parades, floats, banners, and bands remained even after the first frontier stage of progress had passed and the country was well settled. In Illinois, stump speaking was popular as late as 1858, although the frontier had passed on into Kansas and Nebraska, just ready for statehood.

Political PartiesThe slavery question was always a festering thorn in the side of the body politic, frequently poulticed by compromises, but manifesting itself whenever a new national issue arose. The Abolitionists, headed by William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, and others, opposed all compromises and stood for the unconditional and immediate emancipation of the slaves. They were bitterly condemned by both the Whig and Democrat parties as wild and dangerous reformers, who were likely to bring about a dissolution of the Union through their agitation. Each party denied any sympathy for or connection with the Abolitionists.

The contention of the Abolitionists that slavery was wrong ethically, made little progress until it became an economic and political matter through the proposed statehood for Kansas and Nebraska. The prairies were not fitted climatically for cotton raising, which made slaveholding profitable; but if two new States came in free, as they must do under the Compromise of 1820, they would add four free Senators and many free Congressmen to the Northern strength, thereby further curbing the slaveholding power in national affairs.

The demand of the South for an adjustment led, in 1854, to the substitution for the Missouri Compromise of 1820 of a new remedy (the Kansas-Nebraska measure) which, by permitting the people of the proposed states to determine whether they would be free or slave, was thought to be the very essence of democracy or home rule. As usual, in temporizing with the evil the remedy became worse than the disease.

The Republican PartyThis setting aside of the Missouri Compromise for squatter sovereignty banded together Northern Whigs and Northern Democrats on an anti-slavery platform; and they speedily formed a new party, calling themselves Republicans. In 1856 the new party had a candidate for the presidency, Fremont, and parties were now known politically as Democrats, Old Line Whigs, and Republicans. The first two refused to recognize the Republican movement as more than a conspiracy or corrupt bargain between leaders to break up the old parties and bring themselves into political power. In the debates it will be noticed that Douglas assails the corrupt bargain between Lincoln, an Old Line Whig, and Trumbull, a Democrat, both of whom deserted the old parties to join the new Republican party.