THE

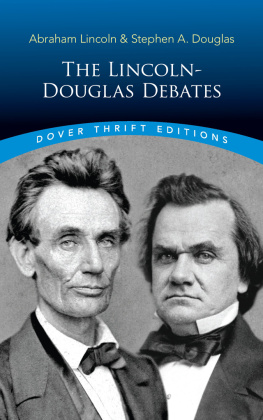

LINCOLN-DOUGLAS

DEBATES

THE FIRST COMPLETE, UNEXPURGATED TEXT

THE

LINCOLN-DOUGLAS

DEBATES

THE FIRST COMPLETE, UNEXPURGATED TEXT

EDITED AND WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

HAROLD HOLZER

Copyright 2004 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates: the first complete, unexpurgated text / Harold Holzer, ed.Fordham University Press ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: 1st ed. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8232-2342-6 (pbk.)

1. Lincoln-Douglas debates, 1858. I. Douglas, Stephen Arnold, 1813-1861. II. Holzer, Harold. III. Title.

E457.4.L776 2004

324.977303dc22

2003069703

Printed in the United States of America

08 07 06 5 4 3 2

Fordham University Press edition, 2004

First published by HarperCollins, 1993

For my daughters,

Remy and Meg... great debaters

Public sentiment is everything

he who moulds public sentiment

is greater than he who makes statutes.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

at the first debate

with Stephen A. Douglas,

Ottawa, Illinois,

August 21, 1858

Contents

Illustrations follow page .

Preface to the Fordham University Press Edition

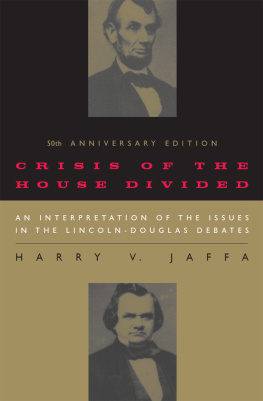

TEN YEARS AGO, the initial appearance of this book unexpectedly set off a small firestorm in the Lincoln scholarly community. Of course, it was nothing like the mammoth explosion of interest that greeted the original Lincoln-Douglas debates. Back in 1858, the debates not only riveted the eyewitnesses who packed town squares and fairgrounds to hear them in Illinois, but also captured the attention of readers around the country who devoured every word in newspaper reprints.

Those very newspaper reprints had provided the inspiration for the 1993 bookas much for what they did not contain as what they did. In the age of Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, Republicans read Republican-affiliated newspapers, which featured debate transcripts recorded by Republican-hired stenographerswho spent far more time polishing Lincolns words than Douglass. Democrats, similarly, read pro-Democratic journals that offered well-prepared versions of the Democratic candidates speeches, and but the roughest versions of his opponents. The purpose of my book was to rescue the long-ignored, and likely unimproved reverse transcriptions of the debatesthose which each party hireling had made of the opposition speakerand therefore try to come as close as possible to the unedited and immediate truth of the most famous debates in American history.

The debates had been republished many times since 1858. But following Lincolns lead in preparing for their initial appearance in book form in 1860, they had always featured Republican-sanctioned transcripts of Lincolns remarks, and Democratic versions of Douglass. Never before had anyone bothered to consult, much less publish, the opposition transcripts: the Republican-commissioned stenographic records of Democrat Douglass speeches and rebuttals, and in turn, the Democratic Partycommissioned transcriptions of what Republican Lincoln said. Instead, for more than a century, readers had come to rely onand unquestionably acceptthe suspiciously well-parsed official transcriptions, undoubtedly edited further by the party press before their final publication, in an era in which newspapers were unashamedly allied with, and biased toward, one political party or another.

So much so, in fact, that Frank Leslies Illustrated Newspaper warned, two years before the Lincoln-Douglas debates got underway, that partisanship among the major publications sometimes exceeded that of their own readers. The bitterness of partizanship, Leslies declared in 1856, and the indulgences of sectional feelings are more rife, in newspapers... than in the feelings of the voters. Considering that such an atmosphere prevailed in 1858, I always wondered why historians had trusted the sanitized, party-made debate records for so long.

Historian Douglas L. Wilson in one sense agreed, commenting about my original 1993 book: In making these opposition texts available, Holzer... performed a rare feat in Lincoln studies: bringing to light for the first time documents of great interest and importance that shed real light on the Lincoln-Douglas debates. But Wilson was troubled by what he called my glaringly circular argument for their truthfulness, contending that the result put modern readers in the awkward position of trusting extremely partisan newspapers without strong and compelling reasons for doing so.

But this was precisely the point for publishing the reverse transcriptsand remains the argument for reissuing this book a decade later: We had too long trusted the accepted texts and transcriptions. This book never intended to provide an unquestionable replacement text of the Lincoln-Douglas debates but, rather, an important alternative record that should be available to the public and judged for its veracity, as are the stenographic reports taken down by supporters of each debater.

Professor Wilson, who published a long review essay about the book in an important Lincoln journal, and later republished it in a book,

This debate about the debates may understandably seem a bit arcane for many general readersa contretemps by, of, and for Lincoln scholars. But it is well worth having, if only because it reminds readers and writers alike of the political culture that inspired such widespread and passionate participation by white men, even as it prohibited involvement by African Americans and women.

I wish I could convince myselfand the new readers I hope will consult this bookthat it was able, in its first incarnation, to widely convey new truths about those historic contests. But, as became all too apparent not too long before the original edition appeared, the debates remain the most egregiously misunderstood political encounters in American history.

In the fall of 1992, the candidates for Vice President of the United StatesRepublican Dan Quayle, Democrat Al Gore, and Ross Perots running mate, Admiral James Stockdalemet for a debate of their own, broadcast on national television. The sound bite of the evening belonged to the Admiral, for declaring, at one point: Why am I here? But he earned additional attention for reporting that he had just read the Lincoln-Douglas debates (the edited and polished transcripts, of course), and was struck by their high tone and broad focus. Like his modern rivals, he charged, Douglas seemed to know all of the little stinky numbers, but Abraham Lincoln had character, and he, Stockdale, would endeavor to demonstrate the same.

The audience cheered lustily, as once and future vice president were both left speechless; the next day, editorial writers lavished praise on the Admiral for elevating political debate back to the once-elegant standard of Lincoln and Douglas. Within days, the

Next page