Copyright

Introduction Copyright 2004 by Dover Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2004, is an unabridged republication of two speeches and seven debates originally published in The Political Debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, published by G. P. Putnams Sons, New York and London, 1913. A new Introduction has been specially prepared for the Dover edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates / Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas.

p. cm.

A selection of two speeches and seven debates originally published in The political debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas in the senatorial campaign of 1858 in Illinois.

9780486145617

1. United StatesPolitics and government18571861. 2. Lincoln-Douglas debates, 1858. I. Douglas, Stephen Arnold, 18131861. II. Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865. Political debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas in the senatorial campaign of 1858 in Illinois. III. Title. E457.4.L77 2004 324.9 77303dc22

2004043898

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

Introduction

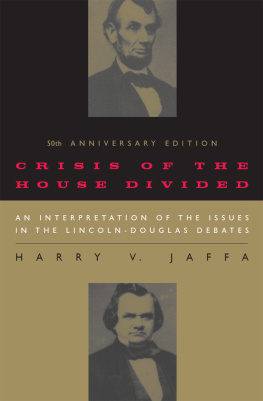

One of the most significant and far-reaching political events in United States history, the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 sharpened and brought to a head a number of crucial questions concerning slavery, states rights, the legal status of blacks, the effects of the Dred Scott decision, and other issues. Although it is difficult today to believe that less than a century and a half ago, men of goodwill on both sides were debating the legality and desirability of enslaving other human beings, such was indeed the case.

The debates were held as part of the campaign for the Illinois senatorial seat in 1858, pitting the two-term incumbent, Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, against the lesser-known Abraham Lincoln, a successful lawyer and state politician, and the Republican candidate. Held in seven congressional districts around the state, the debates (somewhat reluctantly agreed to by Douglas) focused on issues of critical importance to the country, resulting in close attention by the public and the media. Indeed, some thought the future of the nation rested on the outcome. The battle of the Union is to be fought in Illinois, declared one Washington newspaper.

In a sense Lincoln helped lay the groundwork for debate of the slavery question with his famous House Divided speech (p. 1), given in Springfield on June 17, 1858. In that address, he warned that the nation could not survive as half-free and half-slave (A house divided against itself cannot stand.). Moreover, he charged that Douglass popular sovereignty positionallowing the states to decide the slavery issue for themselvesfostered the spread of slavery both in the states and in the western territories the United States had acquired from Mexico. Although Douglas did not like slavery, he liked even less the idea of the federal government telling states what they could or could not do. As an early advocate of states rights, he felt deeply that the people of each state or territory should have the right to decide whether or not slavery was right for them.

Lincoln opposed slavery both on moral grounds (If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.), and political grounds, pointing out that the Declaration of Independence declared that all men are created equal. Surprisingly enough, Lincoln did not consider the black man his social or intellectual equal, but thought he was entitled to equal protection under the law. He saw it as a basic issue of good versus evil, right versus wrong, and he accused his opponent of upholding a wrong.

In his speech in Chicago on July 9, 1858 (p. 10), Douglas accused Lincoln of fomenting civil war by insisting that the states must be either all free or all slave. He was disturbed by Lincolns attempt to settle a controversial moral issue by political means, warning that it could lead to a conflict between the states. He also defended the principle of self-government for states and territories, declaring that uniformity in local and domestic affairs would be destructive of State rights, of State sovereignty, of personal liberty and personal freedom. He further took Lincoln to task for the latters criticism of the Dred Scott decision, in which the Supreme Court decided that all people of African ancestryslaves as well as those who were freecould never become citizens of the United States and therefore could not sue in federal court. As part of the decision, the court also ruled that the federal government did not have the power to prohibit slavery in its territories.

For his part, Douglas maintained that a slave (or an Indian) was not the equal of a white man. I am opposed to giving him a voice in the adminstration of the government. I would extend to the negro, and the Indian, and to all dependent races every right, every privilege, and every immunity consistent with the safety and welfare of the white races; but equality they never should have, either political or social, or in any other respect whatever.

The debates began in earnest on August 21, 1858, in Ottawa, Illinois (p. 26). The question of the extension of slavery into the territories dominated the seven debates. At Freeport, in August, Lincoln asked whether it was possible for the people of a United States territory to exclude slavery from its limits before the formation of a state constitution. Douglas replied that it was up to the people of the territory to allow or ban slavery from that region. This argument was based on Douglas belief that popular sovereignty was compatible with the Dred Scott decision, which ruled that the people of a territory could not exclude slavery. (In a bit of fudging, Douglas said they could do it by means of local legislation.) Known today as the Freeport Doctrine (Slavery cannot exist a day in the midst of an unfriendly people with unfriendly laws.), Douglass opinion caused great controversy throughout America.

During the third debate in Jonesboro on September 15 (p. 109), Douglas accused Lincoln of conspiring with Lyman Trumball, a Democrat who supported Lincoln and the Republican cause, to abolitionize both parties. Knowing there was little chance of gaining much support among the proslavery advocates in attendance, Lincoln wisely refused to respond and again questioned Douglass Freeport Doctrine.

The debates continued on through the fall, with both candidates trying to delineate their own positions, repudiate the accusations, unfair or otherwise, of the opponent, and appeal to the populace for support.

In the fourth debate, at Charleston, Lincoln unequivocally stated that he was not in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people. Moreover, he opined that the physical differences between the white and black races forbade them from living together on terms of social and political equality. Despite this inequality, however, he did not believe that because the white man is to hold the superior position, the negro should therefore be denied everything. As Lincolns speech was given in the southern part of the state, Douglas accused his opponent of pandering to the proslavery South, and that Lincoln took a different tack on equality when addressing audiences in the Abolitionist North.