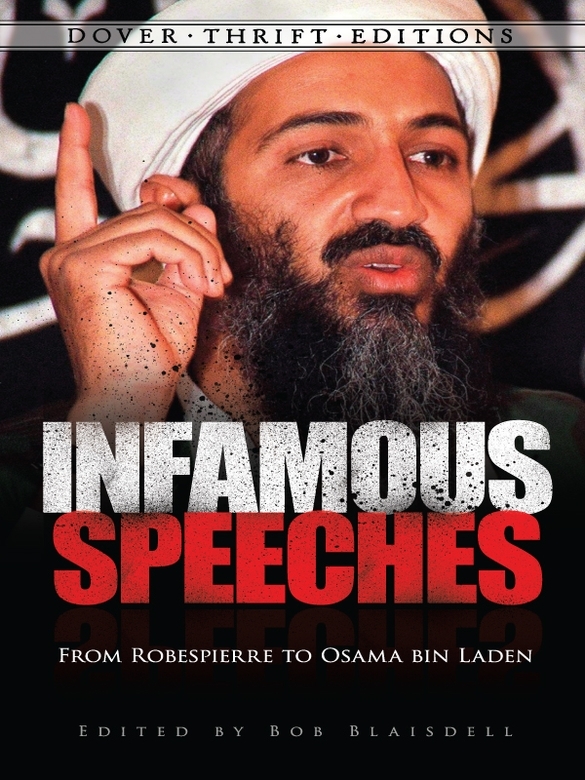

MAXIMILIEN MARIE ISIDORE ROBESPIERRE

The Principles of Political Morality

Address to the National Convention

(Terror is only justice prompt, severe and inflexible... an emanation of virtue;... a natural consequence of the general principle of democracy, applied to the most pressing wants of the country)

Paris, France

February 5, 1794

Maximilien Marie Isidore Robespierre (17581794) was among the French Revolutions most important leaders and most spellbinding of orators. As a member of the deadly Committee of Public Safety, he continues his advocacy for the Reign of Terror against those fighting or challenging the social and legal upheavals the Revolution has wrought. Robespierre saw enemies everywhere and desired the power of terror to obliterate them. Five and a half months later, after his foes gained power, he was executed.

Citizens/Representatives of the People:

We laid before you some time ago the principles of our exterior political system; we come today to develop the principles of our interior political morality.

After having long pursued the path which chance pointed out, carried away in a manner by the efforts of contending factions, the Representatives of the French people have shown a character and a government. A sudden change in the success of the nation announced to Europe the regeneration which was operated in the national representation. But to this point of time, even now that I address you, it must be allowed that we have been impelled through the tempest of a revolution, rather by a love of goodness and a feeling of the wants of our country, than by an exact theory, and precise rules of conduct, which we had not even leisure to sketch.

It is time to designate clearly the purposes of the revolution and the point which we wish to attain. It is time we should examine ourselves the obstacles which yet are between us and our wishes, and the means most proper to realize them, a simple and important idea that appears not yet to have been contemplated. Eh! How could a base and corrupt government have dared to realize it? A king, a proud senate, a Caesar, a Cromwell; of these the first care was to cover their dark designs under the cloak of religion, to covenant with every vice, caress every party, destroy men of integrity, oppress and deceive the people in order to attain the end of their treacherous ambition. If we had not had a task of the first magnitude to accomplish; if all our concern had been to raise a party or create a new aristocracy, we might have believed, as certain writers more ignorant than wicked asserted, that the plan of the French Revolution was to be found written in the works of Tacitus and of Machiavelli; we might have sought the duties of the representatives of the people in the history of Augustus, of Tiberius, or of Vespasian, or even in that of certain French legislators; for tyrants are substantially alike and only differ by trifling shades of treachery and cruelty.

For our part we now come to make the whole world partake in your political secrets, in order that all friends of their country may rally at the voice of reason and public interest, and that the French nation and her representatives be respected in all countries which may attain a knowledge of their true principles; and that intriguers who always seek to supplant other intriguers may be judged by public opinion upon settled and plain principles.

It is necessary to take every precaution to place the interests of freedom in the hands of truth, which is eternal, rather than in those of men, who come and go; so that if the government forgets the interests of the people or falls into the hands of men corrupted, according to the natural course of things, the light of acknowledged principles should unmask their treasons, and that every new faction may read its death in the very thought of a crime.

Happy the people that attains this end; for, whatever new machinations are plotted against their liberty, what resources does not public reason present when guaranteeing freedom!

What is the end of our revolution? The tranquil enjoyment of liberty and equality; the reign of that eternal justice, the laws of which are graven, not on marble or stone, but in the hearts of men, even in the heart of the slave who has forgotten them, and in that of the tyrant who disowns them.

We wish to substitute in our country morality for egotism, integrity for honor, principles for customs, deeds for decorum, the empire of reason over the tyranny of fashion, a contempt of vice for a contempt of misfortune, pride for insolence, magnanimity for vanity, the love of glory for the love of money, good people for good company, merit for intrigue, genius for wit, truth for flash, the attractions of happiness for the ennui of sensuality, the grandeur of man for the littleness of the great, a people magnanimous, powerful, happy, for a people amiable, frivolous and miserable; that is to say, all the virtues and miracles of a Republic instead of all the vices and absurdities of a monarchy.

We wish, in a word, to fulfill the intentions of nature and the destiny of man, realize the promises of philosophy, and acquit providence of a long reign of crime and tyranny. That France, once illustrious among enslaved nations, may, by eclipsing the glory of all free countries that ever existed, become a model to nations, a terror to oppressors, a consolation to the oppressed, an ornament of the universe and that, by sealing the work with our blood, we may at least witness the dawn of the bright day of universal happiness. This is our ambition; this is the end of our efforts.

What kind of government can realize these wonders? Only a democratic or republican governmentthese two words are synonyms, despite the abuses in common speech, because an aristocracy is no closer than a monarchy to being a republic. A democracy is not a state where the people, continually assembled, regulate all the public affairs themselves; much less is it one where a hundred thousand groups of people, segregated by measures, hasty and contradictory, decide the fate of the whole nation: such a government has never existed except to bring back the people under the yoke of despotism.

Democracy is a state in which the sovereign people, guided by laws which are of their own making, do for themselves all that they can do well, and by their delegates do all that they cannot do for themselves.

It is therefore in the principles of a democratic government that you are to seek the rules of your political conduct.

But, in order to found and consolidate among us democracy, to reach the peaceful reign of constitutional laws, we must terminate the war of liberty against tyranny, and weather successfully the tempests of the revolution. This is the end of the revolutionary government you have framed. You should therefore again regulate your conduct by the tempestuous circumstances in which the Republic exists, and the plan of your administration should be the result of the spirit of the revolutionary government combined with the general principles of democracy.

Now, what is the fundamental principle of popular or democratic government, that is to say, the essential mainspring which sustains it and gives it motion? It is virtue. I speak of the public virtue that worked so many wonders in Greece and Rome and ought to produce even more astonishing things in republican Francethat virtue which is nothing else than the love of the nation and its laws.

But as the essence of the republic or of democracy is equality, it follows that love of country necessarily embraces the love of equality.