Table of Contents

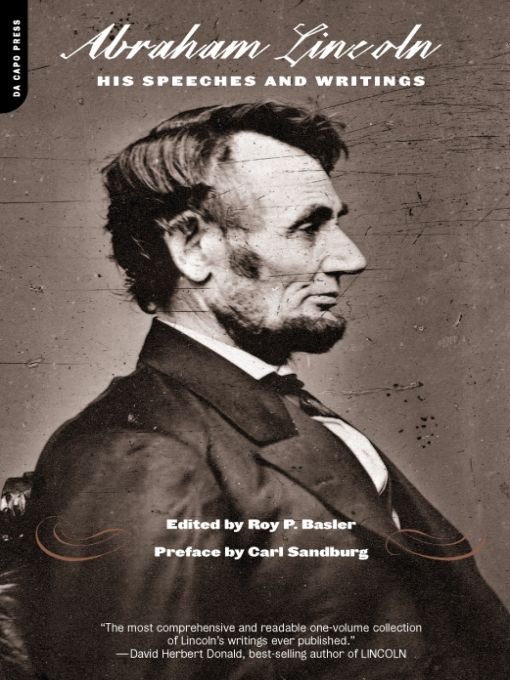

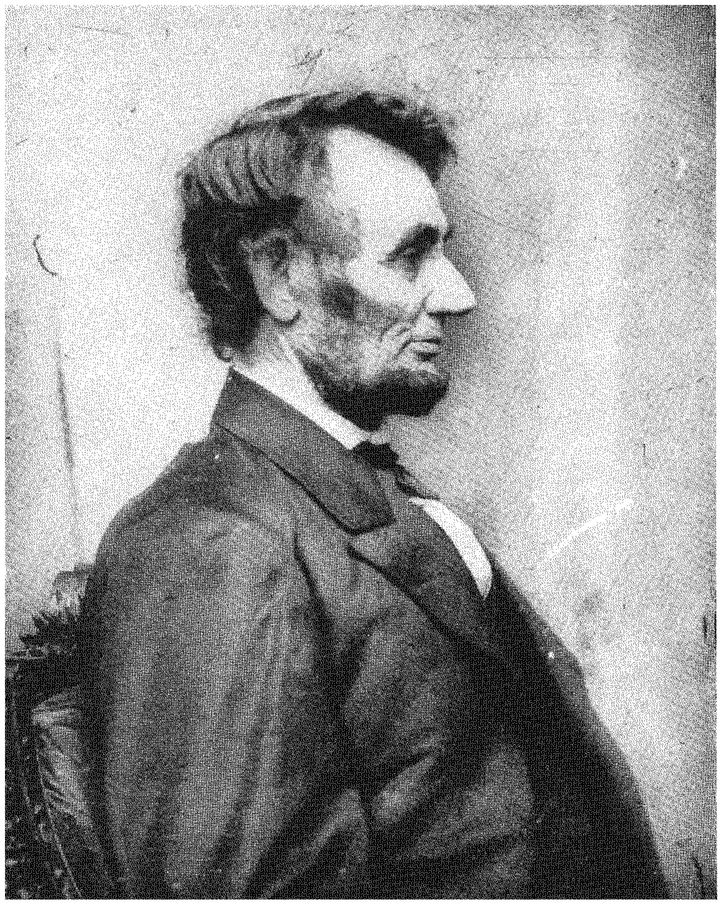

Meserve No. 82. A photograph made by Mathew B. Brady on February 9, 1864. Victor D. Brenner used this photograph in making his design for the Lincoln penny. The original glass negative is in the Meserve Collection.

To my Father

ILLUSTRATIONS

Brady Profile of Lincoln, February 9, 1864. Meserve Collection, No. 82

Frontispiece

Cooper Institute Portrait of Lincoln, by Mathew B. Brady, February 27, 1860. Meserve Collection, No. 20

Photograph of Lincoln, by Alexander Hessler, June 3, 1860. Meserve Collection, No. 26

Inaugural Photograph of Lincoln, by Mathew B. Brady, February 23, 1861. Meserve Collection, No. 68

Photograph of Lincoln, by Mathew B. Brady, February 9, 1864. Meserve Collection, No. 85

Last Photograph of Lincoln Made in Life, by Alexander Gardner, April 10, 1865. Meserve Collection, No. 100

Facsimile of the Hooker Letter

THE PHOTOGRAPHS of Lincoln which illustrate this book are from the Collection of Frederick Hill Meserve. Mr. Meserve, whose prodigious research in Lincoln likenesses dates back to the turn of the century, is regarded as the leading authority on the subject. Arranged chronologically, these photographs record Abraham Lincoln, the man, during the momentous last five years of his life.

There has been no touching-up or removing of blemishes in order to make more perfect pictures. The original photographs in the Meserve Collection have been copied with absolute fidelity.

THE FACSIMILE of Lincolns letter to General Hooker, which appears on page 844, is used by permission of the owner of the original letter, Mr. Alfred Whital Stern of Chicago. It was made from a half-tone reproduction issued by R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company for the Chicago Caxton Club.

PREFACE

HE HAS a style his own, has often been the comment on a writer or speaker. When it was said of Walt Whitman it meant that any imitation of his style, so distinctive was it, could at once be seen as mimicry. One result of this was many parodies.

And though we sometimes meet the expression, a Lincolnian style, it has no strict meaning as in the case of Whitman. Lincoln had many styles. It has been computed that his printed speeches and writings number 1,078,365 words. One may range through this record of utterance and find a wider variety of styles than in any other American statesman or orator. And perhaps no author of books has written and vocalized in such a diversity of speech tones directed at all manners and conditions of men.

This may be saying, in effect, that the range of the personality of Abraham Lincoln ran far, identifying itself with the tumults and follies of mankind, keeping touch with multitudes and solitudes. The freegoing and friendly companion is there and the man of the cloister, of the lonely corner of thought, prayer, and speculation. The man of public affairs, before a living audience announcing decisions is there, and the solitary inquirer weaving his abstractions related to human freedom and responsibility.

Perhaps no other American held so definitely in himself both those elementsthe genius of the Tragicthe spirit of the Comic. The fate of man, his burdens and crosses, the pity of circumstance, the extent of tragedy in human life, these stood forth in word shadows of the Lincoln utterance, as testamentary as the utter melancholy of his face in repose. And in contrast he came to be known nevertheless as the first authentic humorist to occupy the Executive Mansion in Washington, his gift of laughter and his flair for the funny being taken as a national belonging.

Thus Lincoln, by plain reasoning, would overcome, or by a story of pointed humor would reduce the opponents position to absurdity, and this was often his aim and method as a writer and speaker.

How he moved and spoke as a part of the human comedy became vivid mouth-to-mouth folklore while he was alive, and his quips and drolleries went beyond his own country to lighten the brooding and speaking figure of Lincoln in the human tragedy. And so began the process by which he was internationally adopted by the family of Man.

Not yet has there been compiled and annotated a complete collection of the speeches and writings of Abraham Lincoln. No definitive work in this field has as yet come into existence. If there were such a work it would be heavy to use, it would be loaded with repetitious material, it would be cumbersome, definitely lack convenience, certainly not a handy volume. Of course such a complete and definitive collection of Lincoln utterances is wanted and needed. There are those students of Lincoln who give themselves the assignment of reading every last available word written or spoken by Lincoln. The statesman and politician, the executive, the humorist, the literary artist, the great spokesman of democracy, the simple though complicated human being Abraham Lincoln, is best to be known by an acquaintance with all that he wrote and said. For large masses of people however this wont do. They must live and work and time counts and in small houses room, just plain cubic space wherein to keep things, has to be considered. Therefore, says Mr. Roy P. Basler, why not one book, a single volume, holding the best and the most indispensable of Lincoln utterance? In having read this book, who is to stop you from going farther, if you are interested?

Basler is out of Missouri, the Show-Me State, born in St. Louis November 19, 1906, a graduate of Central College, Missouri, a high school English teacher (1926-28) in Caruthersville, Missouri, in the southeastern heel of that state, often designated as Swamp-East Missouri. A terrain it is where during the War of the 1860s nobody could always be sure just who to shoot. Should you sometime visit the battle area around Vicksburg they can show you a hill held by Missouri Confederate troops attacked by Missouri Federals. Roy Basler as boy and youth grew where he heard and saw many sides of the argument and elemental passions that brought on the war. The vernacular and slang of Lincolns southern Illinois and Kentucky soil are native and familiar to Basler.

It didnt hinder him any to go down to North Carolina and work for a Ph.D. at Duke University, there meeting Jay B. Hubbell, Professor of American Literature, a scholar and seeker. Their conversation one hot summer evening in 1930 drifted around, says Basler, to Lincolns literary style and the numerous treatments of Lincoln in fiction, poetry, drama, letters, diaries. From this talk burgeoned and developed Baslers doctoral dissertation, Abraham. Lincoln in Literature: the Growth of an American Legend. Also at Duke, Basler married a South Carolina girl of whom he says, Without her help and sympathetic understanding of my aims and endeavors, I couldnt have gone through with the labors required. As a family the Baslers have arithmetical balance two boys, two girls; and a handsome, vital group they are singing The Arkansas Traveler and Whoa Mule Whoa.

In colleges at Sarasota, Florida, and Florence, Alabama, Basler taught English and American literature, twelve months in the year for the most part, largely to Southern students though his classes always had young folk from Northern and Western states. His years of final painstaking labors on this present book have been at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, from which place he wrote to his loyal and indefatigable Chicago friend Ralph Newman of the Abraham Lincoln Book Shop: I suppose that it would be a pleasure to teach Lincoln, Emerson, Melville, Walt Whitman and Mark Twain, to college students anywhere; but I doubt that it could be any more fun than it is in the South, where although we still have our Bilboes we have also our Lister Hills and our J. W. Fulbrights (Bill Fulbright is a hometown boy here in Fayetteville). The America that means most to me is less her rocks and rills, etc., than her Jeffersons and Lincolns. I use the plural advisedly in speaking of those nonpareils, for when a Southerner can go to Chicago and meet an Oliver R. Barrett, or a Middlewesterner can go to Durham, N. C., and meet a Jay B. Hubbell he learns that what was Jefferson, and what was Lincoln, still is and will be.