Note

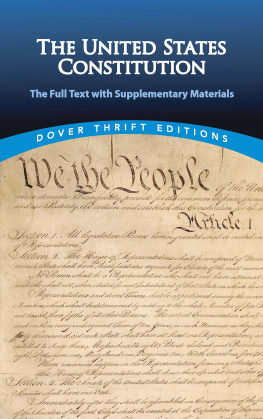

ITS ENLIVENING AND enlightening to read about events as they happen through these 154 documentsdating from 1606 to 2008that make us eyewitnesses to history. For example, during the Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1787, we can imagine some of the Founding Fathers shaking their heads ruefully during the debate over the continuance of slavery.

George Mason of Virginia lamented, Every master of slaves is born a petty tyrant. They bring the judgment of heaven on a country. As nations cannot be rewarded or punished in the next world they must be in this. Was Mason prescient about the Civil War of 18611865 or simply possessed of an unusually acute moral sense?

In 1789, we learn through his first Inaugural Address that George Washington was apprehensive as he warily accepted the duties of president of the newly established nation: Among the vicissitudes incident to life no event could have filled me with greater anxieties than that of which the notification was transmitted by your order ... On the one hand, I was summoned by my country, whose voice I can never hear but with veneration and love, from a retreat which I had chosen with the fondest predilection, and, in my flattering hopes, with an immutable decision, as the asylum of my declining years ... Less than three years after serving his second term of office, the great man died at the longed for asylum of his Mount Vernon home.

Thomas Jefferson, the primary author in 1776 of the Declaration of Independence, was, as the third president, excited as he imagined the world that his chosen proxy, Captain Meriwether Lewis, would encounter in the wilderness in and beyond the recently purchased Louisiana Territory and made his way to the Pacific Ocean. More than any other U.S. president of the eighteenth century, Jefferson demonstrated respect for the native peoples by instructing Lewis:

In all your intercourse with the natives treat them in the most friendly & conciliatory manner which their own conduct will admit; allay all jealousies as to the object of your journey, satisfy them of its innocence, make them acquainted with the position, extent, character, peaceable & commercial dispositions of the U. S. of our wish to be neighborly, friendly & useful to them, & of our dispositions to a commercial intercourse with them; confer with them on the points most convenient as mutual emporiums, & the articles of most desirable interchange for them & us. if a few of their influential chiefs, within practicable distance, wish to visit us, arrange such a visit with them, and furnish them with authority to call on our officers, on their entering the U. S. to have them conveyed to this place at public expense. if any of them should wish to have some of their young people brought up with us, & taught such arts as may be useful to them, we will receive, instruct & take care of them, such a mission, whether of influential chiefs, or of young people, would give some security to your own party, carry with you some matter of the kine-pox, inform those of them with whom you may be of it efficacy as a preservative from the small-pox; and instruct & encourage them in the use of it. This may be especially done wherever you winter. (We have preserved Jeffersons clipped and special spellings.)

Native American oratory is justly admired, and as recorded by witnesses, we can read the speakers cogent arguments and discourses about this great land they love and the naive concessions they made to the multitudes of immigrants from across the Atlantic. In 1811, Tecumseh, the chief of the Shawnees, tried to unify various tribes in an alliance against the encroaching, treaty-breaking European settlers. When we learn that his persuasive, carefully reasoned arguments fell on deaf ears, we can only wonder what else he might have said to convince them.

Too often as students of history we are like readers of tragedies, hoping that what we know is about to happen wont. Would Senator John C. Calhoun, a firebrand from South Carolina, really have stoked the flames of secession by defending and lauding the regions peculiar institution of slavery had he known the consequences of the Civil War, in which more than 600,000 soldiers died? Could this country of immigrants really have set out on genocidal policies against the Native peoples? As proud as we are to be Americans, our history will often shock us. Along with the glory of unprecedented achievement, there is also the shame and regret of injustice and wrongdoing.

But its not over until its over; improvements beckon. Lord knows we havent achieved gender or racial equality yet, much less agreement about health care, economic and international policy, or guns and drugs. Our history shows that weve made tremendous moral progress, that in spite of each ages prejudices and limitations, we are driven toward making adjustments and corrections.

Political stand-offs can be infuriatingly frustrating, no doubt about it, and if we werent much more than political animals, it would be hard to feel hopeful. But Americans are social beings, and at our best were curious and reflective, and we can clearly see the veering of our nations course in retrospect while wondering where were veering now. The leaders of the American Revolution seemed to have no intention of declaring independence until they did so; the history they encountered and created surprised them, and someday the history were making now will surprise us too. In fact, a few of the more recent documents can evoke memories of unexpected events of our own time. For instance, the 9/11 Commission Report recounting the minute-by-minute confusion and terror of the attack on the World Trade Center towers may stir haunting memories from that day for many readers.

Does our sense of history lay too much blame or credit at the feet of politicians, who, in their twists and turns, bombast and eloquence, we see speaking to the wishes and furies of the people? Probably! But these documents are not just written or spoken by the privileged; they include the bewildered and outraged viewpoints of the comparatively powerless. In his 1852 address, What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July? the ex-slave Frederick Douglass, one of the most extraordinary Americans in our history, forcefully expresses the contradictory feelings in the air: I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony.