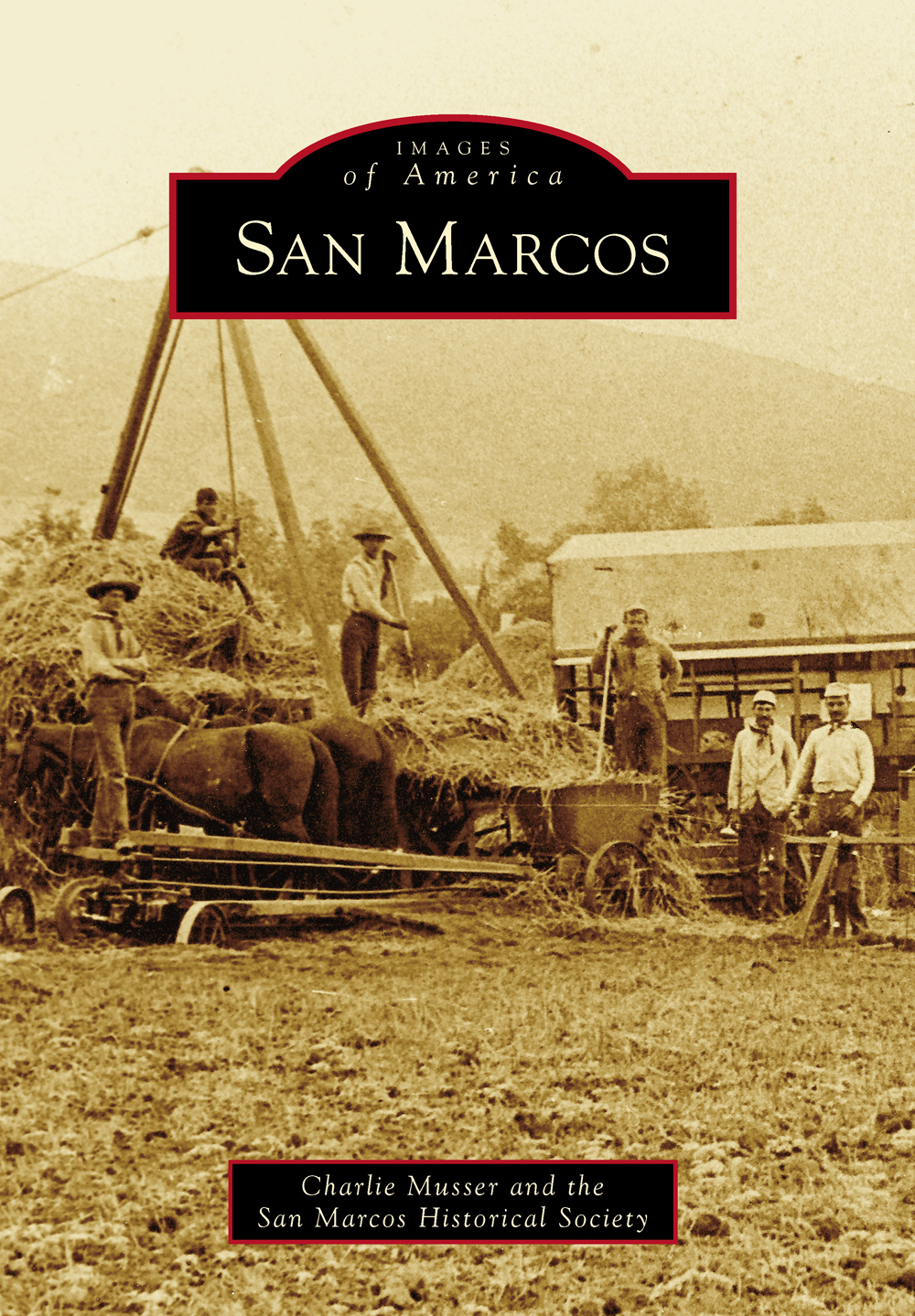

IMAGES

of America

SAN MARCOS

The Twin Oaks Valley was named for this enormous oak tree with a double trunk, which grew on the property of Major Gustavus French Merriam, one of the first homesteaders in the San Marcos area. In the 1980s, the rotting tree was damaged by lightning and was cut down. A new oak growth has now sprouted in its place. (Courtesy of San Marcos Historical Society.)

ON THE COVER: Early sustenance in San Marcos relied heavily on hay and grain farming, with hay baling and threshing crews a common sight. Crews were made up of local men and worked sunrise to sunset, six days a week. Seen here is the Huchting hay baling crew, with Henry Huchting standing at the far right. (Courtesy of San Marcos Historical Society.)

IMAGES

of America

SAN MARCOS

Charlie Musser and the San Marcos Historical Society

Copyright 2014 by Charlie Musser and the San Marcos Historical Society

ISBN 978-0-7385-9962-5

Ebook ISBN 9781439645048

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012951743

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To all those whose lives have vanished from history like adobe bricks back into earth.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication would not have been possible without the years of research, organization, and documentation done by previous members of the San Marcos Historical Society. Foremost is Ruth Lindenmeyer, who first organized the societys newspaper clippings and documents and conducted numerous interviews with local pioneer families, chronicling information that otherwise would have been lost with passing generations. Also, I thank William Carroll and Roy Haskins, whose past publications were invaluable references.

I owe immense thanks to current members of the society, who trusted me to produce the first book on San Marcos history in almost 40 years after only a few months of volunteering. Specifically, thanks to Tanis Brown for making me feel welcome since my first day, Mimi Kennedy for square dancing her way into my life, forever young Maryanne Cioe, and Jackie Hartley (I wish I could have had a meal under the mural at Hartleys Steak and Eggs).

Numerous families must be given thanks for photo donations including the Astleford, Bucher, Fulton, Huchting, Merriam, and Tobin families, although the list is so numerous, my apologies for not naming them all specifically here. The photographers known to have supplied images in this publication include Dan Rios, as well as Cenizom, Cosentino, Doyle, Drake, Edwards, Franklin, Kreisler, and Nilo, whose first names are unknown.

I must thank Mark Mojado, Cami Mojado, P.J. Stoneburner, and Paul Price who trusted me with sensitive information and made me feel like family since our first meeting. Further consultation and photographs came from numerous sources including Rachel Caldwell and the Golden Door Spa, Blake Isaac and Questhaven Retreat, San Marcos Brewery, the San Elijo Hills Visitor Center, and Alicia Yerman and the Vallecitos Water District.

Lastly, I must thank my family: my companion Rejoy Armamento for supporting me in innumerable ways; my Grandpa and Granny (who attended the 1910 schoolhouse) for supporting every crazy idea I conceive; my sister Malia, who keeps me in check; and my Mom, without whom I would never have had this opportunity.

Unless otherwise credited, all images come from the photograph collection of the San Marcos Historical Society.

INTRODUCTION

Many moons have passed since San Marcos was only inhabited by the Luiseo Indians, who lived a semi-nomadic lifestyle, moving periodically to areas between Palomar Mountain and the Pacific Ocean. Tribes would migrate in order to keep from depleting natural resources, and San Marcos was one of numerous areas where tribes set up semi-permanent villages, most likely during the colder seasons when Palomar Mountain was blanketed with snow.

Legend states that the first sighting of San Marcos, by persons other than indigenous inhabitants, was by a company of Spanish soldiers in pursuit of suspected Indian horse thieves. While the troops lost track of the suspected culprits, they happened to find themselves in a secluded landscape made up of small valleys. As the date was April 25, the feast day of St. Mark, the soldiers named the area Los Vallecitos de San Marcos, which translates to the Little Valleys of Saint Mark. By 1798, Fr. Fermn Lasun had established Mission San Luis Rey de Francia a few miles west, and the San Marcos area came under control of the Spanish government. Local Luiseo customs were deemed primitive, and a program of religious conversion, slavery, and assimilation was established by the Franciscan clergy. With the introduction of foreign diseases to which most tribes had no immunity, Spanish presence caused the native population to be cut in half within a quarter of a century, and a way of life practiced for multiple millennia was erased.

Following the Treaty of Crdoba in 1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain, ushering in the California rancho period. San Marcos was utilized mainly as open grazing land, inhabited only by the dwindling population of remaining Luiseos and ranch hands employed by the owners of Rancho Los Vallecitos de San Marcos, officially established as a Mexican land grant in 1840.

One unfortunate fact when dealing with history is that not all people or buildings leave a trace of their existence. An 1895 account of San Marcos states that five old sea captains lived in the area, but only the name of a Captain O Brien is recorded. San Marcos was also definitely home to at least some Japanese immigrants, but following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese population was sent to relocation camps, and the local family names of Tannaka, Yammamto, Yasakocha, and others are left without a recorded story.

Architectural remains of any buildings once standing on rancho land have yet to be found, but accounts of multiple adobes scattered throughout the region exist as the only impression that any structures ever stood in San Marcos prior to 1875. Adobe houses are reported to have stood on the Frood Smith ranch and Merriam ranch, along with an adobe sheep grazing headquarters on the Bass ranch, formerly owned by John Hanson and the supposed site of long-lost buried treasure. Reports exist of early sheepherders driving flocks of hundreds of sheep down Mission Road, even up until the early 1900s.

San Marcos endures as an area steeped in myths and legends, which remain as the more lasting testimonies between multiple generations. The lost treasure at the Bass ranch was supposedly a horde of gold wrapped in a horsehair blanket, buried somewhere near the property by a sheep owner who was subsequently murdered by his employees. For years, the area was cratered with holes dug by treasure seekers, including a speculator from Long Beach who arrived so convinced of finding the cache that he had even made arrangements with his bank to handle his newfound wealth. The only prize the gentleman found was a tiny piece of metallic substance stuck on a giant boulder underneath a haystack.

Other treasure seeking stories include a gold mine operated by two brothers following World War I in the northern portion of the Twin Oaks Valley and three strangers arriving on the Taite ranch with a map asking to dig, only to disappear by the next morning. Legends further claim that on certain nights, areas of the San Marcos valleys are said to glow like small fires and are believed to show where stolen treasures buried by Mexican bandits exist. Marcelino Couro, a local sheepshearer, documented that while traveling from Oceanside to San Pasqual, he passed through San Marcos and saw this ethereal light. Couro claims that he hired two local laborers who, deep into the night, helped him dig in the spot where he had seen the light. Couro then went to sleep and upon waking found only a large hole and two empty rawhide bags.

Next page