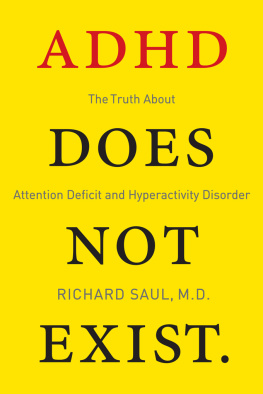

I dedicate this book to all the children and adults who have been misdiagnosed with ADHD and have had their treatment delayed or denied.

We are to admit no more causes of natural things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain their appearances. Therefore, to the same natural effects we must, so far as possible, assign the same causes.

I SAAC N EWTON

Listen to the patient, and they will give you the diagnosis.

S IR W ILLIAM O SLER, COFOUNDER OF J OHNS H OPKINS M EDICAL S CHOOL

Contents

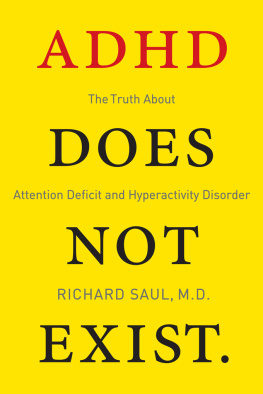

T hroughout this book, I will use the term ADHD as a form of shorthand for talking about the group of attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms that have gained that label through the American Psychiatric Association, the DSM , and the multiple parties that have embraced it. Moreover, in multiple places in the book Ive noted how or where ADHD and other diagnoses overlap. In all cases, my intention is for you to read ADHD as the set of symptoms associated with that diagnosis, rather than taking my use of the diagnostic term literally. If I meant the latter, this book wouldnt exist. Also, for the inquisitive reader, I encourage you to turn to the Notes section after reading each chapter for more details and resources.

I wrote this book to be provocative. Not provocative for the sake of provocation, but because I have been concerned for years about the multifaceted problems caused by the misdiagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, in children and adults. Attention-related symptoms are all too real, with negative consequences for children, adults, and broader society; those affected face challenges in academic, professional, and social settings, often with lifelong repercussions. But the medical establishments reliance on the ADHD diagnosisand the medical communitys embrace of ithas also had several negative consequences: the failure to diagnose underlying conditions that explain attention symptoms in whole or in part; the omission of much-needed treatment for those primary diagnoses; the health-related, economic, and emotional costs of undiagnosed and hence untreated conditions. I wrote this book to provoke deeper thinking about debilitating attention-deficit and hyperactivity symptoms for practitioners, patients, and others, with the hope that it will help more people get the help they need.

My route to gaining a complete picture of attention-deficit symptoms has had multiple turns. An early experience with attention symptoms arose through my faculty position as professor of clinical medicine with the University of Health Sciences in Chicago. Starting in the 1970s, I was responsible for establishing new programs that would engage and educate medical students and faculty about medical conditions that could interfere with learning. In this role I started a program to identify factors interfering with childrens learning (kindergarten through eighth grade) in the Lake County, Illinois, school system. Our guiding question was Whats preventing them from learning? From our first day in the schools, one observation stood out: A very high percentage of the childrenmore than one in fivefaced attention challenges. These took the form of learning problems, disruptive behavior, even sadness and withdrawal. Over time, I developed a protocol for evaluating children with attention-related issues and others that interfered with learning. I still remember the stack of articles I went through to develop the protocol: It was taller than I was, more than six feet high!

At the time, I still held a conventional view of the attention deficit diagnosis. We called it attention-deficit disorder, or ADD (the Hyperactivity part would come later), which remains a very popular acronym for the condition. Among our research questions were Do all children with learning disabilities have ADD? (they didnt) and Do all children with ADD have learning disabilities? (most did, but they also had higher IQs than their average peer). I didnt realize it at the time, but one of the components I developed for the Lake County schools program laid the foundation for my eventual belief that attention deficit and hyperactivity were symptoms rather than a diagnosis. To help our medical students understand the challenges associated with attention deficits, we simulated the classroom experience for them, for example by having them wear reverse binoculars that made everything look farther away than it really was. Due to their compromised depth perception, students wearing the binoculars tended to knock items off their desks and accidentally bump into other students when moving around the roomboth hallmark signs of ADHD. Similarly, we had the medical students wear headphones that transmitted lecture material, but with brief, frequent periods of silence (that is, gaps in the audio feed) that made comprehension difficult, another symptom of attention deficit or a learning disorder. In retrospect I realized that I was simulating not only attention deficits but many of their underlying causes . As well see in later chapters, vision and hearing problems, or even absence seizures, are responsible for a significant number of patients misdiagnosed with ADHD. Not surprisingly, once we had students take off the binoculars or headphones their ADHD symptoms disappeared.

Another influence on my thinking about attention deficit arose soon after my experience at Lake County schools, but from a very different source. The mother of a patient named Bobby, a fourth grader, told me that Bobbys teacher had called her in for a meeting because he was disrupting the class. Bobbys mother said she was surprised, given his record of good classroom behavior up to that point. I asked her to find out if her son was engaging in the behavior all day or only during certain periods. On her next visit she reported that Bobby was only disruptiveincluding throwing spitballs, talking to classmates, and tapping his fingers on his deskduring the classs math section. Moreover, Bobby, who tested as gifted in most subjects, had already completed the entire fourth-grade math curriculum in the first month of school. Now my patients behavior made more sense: He was probably bored. Bobbys mom confirmed that he was expected to sit and be quiet while the others did their exercises. It would have taken a rare fourth-grade boy to toe that line! I helped Bobbys mother arrange for him to attend a fifth-grade math class. His disruptive behavior disappeared overnight. Importantly, I saw again how a specific conditiongiftedness, in this casecould manifest itself through attention-deficit symptoms. Bobby wasnt diagnosed with ADHD, but it was easy to see how a child like him in different circumstances might be. One of the chapters in the book is devoted to children like Bobby, whose talent can lead to boredom and a misdiagnosis of ADHD.

In the early 1980s I began to pursue my evolving hypothesis about attention deficit and hyperactivity more fully. I had won a multi-year federal grant to work with a director of special education to raise statewide awareness of childrens learning and attention issues. But our work also raised my own awareness of institutionalized problems related to these issues. For example, it became clear that physicians werent performing comprehensive examinations of children with attention/learning deficits, even though that was suggested by the American Academy of Pediatrics and other leading medical organizations. There were multiple reasons for this. Among them were knowledge gaps (doctors just didnt know how to examine these patients) and economics (securing full reimbursement for such evaluations was becoming increasingly difficult). These and related observations motivated me to open a referral office in 1983. A referral office is one that handles patients sent by other physicians, psychologists, and other patients, usually because the patients represent complicated cases or fail to respond to initial treatments. Many of the patients sent to me had already seen multiple doctors, with no relief.