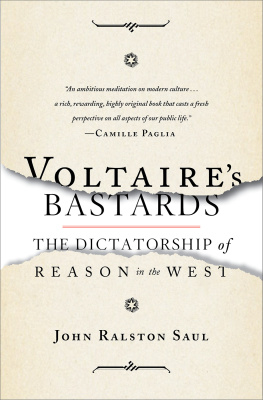

Acclaim for

VOLTAIRES BASTARDS

Saul covers politics, diplomacy, the military, the arts, literature, painting, and almost everything else, in each case providing a lucid and entertaining anatomy of perversion.

The Times (London)

Sauls work is peopled with villains from four centuries. He compares Cardinal Richelieu to Robert McNamara and the Society of Jesus to the Harvard Business School with considerable appositeness. His character portraits, such as that of James A. Baker, are inspired.... The section on the international arms trade alone makes the book worth its weight.

Boston Globe

A passionate and personal tour of the follies of our age. The banner of Reason, he claims, can as easily lead to disaster as to victory. Scientists are only one of the groups that can readily identify with this argument.

John Polanyi, Nobel Prize for Chemistry, 1986

Saul has decided to take the axe to the root and to challenge the assumption that our method is one of rational choice.

Christopher Hitchens, Newsday

An important book [that] ought to generate the kind of serious intellectual debate that weve been missing in the past five years.

Russell Banks

Voltaires Bastards may be one of those rare books that changes the way society sees itself... brilliant.

McLeans

NOVELS BY JOHN RALSTON SAUL

The Birds of Prey

Baraka

The Next Best Thing

The Paradise Eater

John Ralston Saul

VOLTAIRES BASTARDS

John Ralston Saul holds a Ph.D. in history from Kings College (London), ran a Paris-based investment firm, worked as a Canadian oil executive, and has written extensively about North Africa and Southeast Asia. His most recent novel, The Paradise Eater, won the Premio Letterario Internazionale in 1990.

Contents

For

MAURICE STRONG

who taught me that a sensible relationship between ideas and action is possible.

Ecartons ces romans quon appelle systmes;

Et pour nous lever descendons dans nous-mmes.

V OLTAIRE

Twenty Years On

The ability to embrace doubt in the middle of a crisis is a sign of strength. Voltaires Bastards ends with what might seem a surprising eulogy to doubtour ability to live with uncertainty as a creative force. You could call this an expression of consciousness. If we can bring ourselves to live consciously then we will be able to embrace both stability and change, which means we may do better at dealing with crises.

That eulogy to doubt included descriptions of what I have seen over the years in both the Arctic and the Sahara. Existing in doubt is a strength of people who live in extreme conditions. They must be conscious or they will die.

We, flowers of the temperate zones, can float half awake through a padded world. We have our dramas and our suffering. But most of that we impose upon ourselves.

The greatest drama we have imposed on ourselves is our willful misinterpretation of consciousness. The Socratic conviction was that virtues were forms of knowledge and therefore no man willingly does wrong. What I said in Voltaires Bastards about our modern elites was that, by abandoning humanism in favour of an ideology of reason, they had inverted the equation. Now they justify doing wrong because they do know. This rational sophistication makes them passive, terrified of uncertainty, unable to change when faced by reality, ready to accept the worst.

You might call this profound cynicism: the mindset of the courtier or consultant or advisor. In any case, they believe themselves to be immobilized by what they know. This, they think, is professional behaviour. To be precise, they know so much that they believe it would be amateurish or emotive to do anything much about the environment, global warming, poverty, debt, to mention just a few problems.

This passive or fearful mind-set, tied to expertise and power, has steadily worsened over the last twenty years as the power of managerial leadership has grown. Theirs is a mind-set obsessed by systems and by control over systems as the essence of power. It is the opposite of leadership. It is all about form over content; a mind-set in which continuity and mediocrity are the same thing.

Today their power is such that they feel comfortable manacling the citizenry with debts transferred to them from corporate bodies. They take pleasure in weighing job creation against planetary warming, as if these were opposites. It is as if they, being experts, had cleverly negotiated a deal with the planet itself. A trade off. As simple as that.

Is this naivety? Ignorance? Even Odysseus knew you couldnt do a deal with Zeus.

I mentioned in Voltaires Bastards that the late twentieth century resembled the mid-eighteenth, with a large, sophisticated, self-referential and pessimistic elite. This is what you might call the self-destructive nature of the overly sophisticated. Twenty years later this also is increasingly true: We have an elite pessimistic not only about its own ability to do things but, thanks to an astonishing transfer of responsibility, pessimistic about the citizenry.

In the early 1990s it seemed to me that we were trapped in a social crisis, only one part of which was an economic depression. But this was a rare sort of depression, broad and deep-seated; a tailspin downwards brought on by the worship of uninteresting methods. We seemed unable to ask ourselves serious questions about our civilizations and about where they were headed. Such a tailspin wasnt so much about economics as about philosophy. It isnt economics that leads to a class system or a rich-poor divide or, alternatively, to attempts at inclusion and egalitarianism.

All of this is dependent on how we imagine ourselves, as well as how we imagine all those other people we simply do not know. Can we imagine the other? Are we capable of empathy? For those who carried the most influence in the nineties, this was not a central question.

And for many, the idea that we were caught in a long-term tailspin was outrageous. They were immersed in their proofs of progress. And of course, looked at selectively, they were right. There had been continual breakthroughstechnological, digital, medical. Just as there are today. But then the second half of the eighteenth century was also one of continual breakthroughs in science, in technology, in agriculture, in philosophy, in understanding how the planet functions. These breakthroughs were perhaps more revolutionary than those of the late twentieth century. After all, they carried the West clearly out of the Middle Ages.

The elites of the eighteenth century did not understand or respond to the instability that all these changes brought on. They saw social and political methods and the structure that protected their role as inviolable. Doubt in any of this might bring it all tumbling down. Doubt was therefore banished. And then it did all come tumbling down. What followed was an era of revolution, violence and dictatorships. And there was a surprising focus on race; that is, a surprising focus on the scientific, free-market, nation-state application of racism. From there the triumph of reason moved on to produce a world dominated by a handful of empires. These in turn were characterized by those same elements of revolution wherever they set up shop: violence, dictatorship, institutionalized racism, all served by science and the free market to the benefit of that handful of nation-states.

What of today? Well, we see what passes for political, administrative and intellectual leadership still hanging on desperately to old-fashioned concepts of trade and growth, to name but a few of their favourite things. They seem to believe in the sanctity of the commercial contract, but see no equivalent sanctity attached to the well-being of the citizenry. They have a moral fervour when it comes to other peoples debts. In fact, they have become increasingly religious about their utilitarianism, turning poor Adam Smith into their saint without reading him or, worse still, after reading a few extracts. So its not surprising that their capacity to embrace uncertainty seems, if anything, to be shrinking. And their still-growing obsession with method rather than purpose strikes me as psychotic. You can see this in the energy with which much of our education is being pushed towards the utilitarian. Training, not education.

Next page