Elizabeth Lyon - A writers guide to fiction

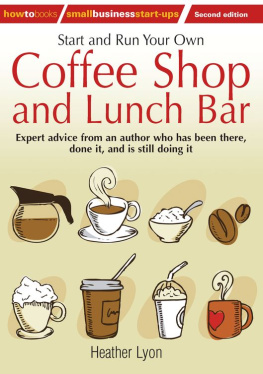

Here you can read online Elizabeth Lyon - A writers guide to fiction full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2004, publisher: Penguin, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A writers guide to fiction

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin

- Genre:

- Year:2004

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A writers guide to fiction: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A writers guide to fiction" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A writers guide to fiction — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A writers guide to fiction" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

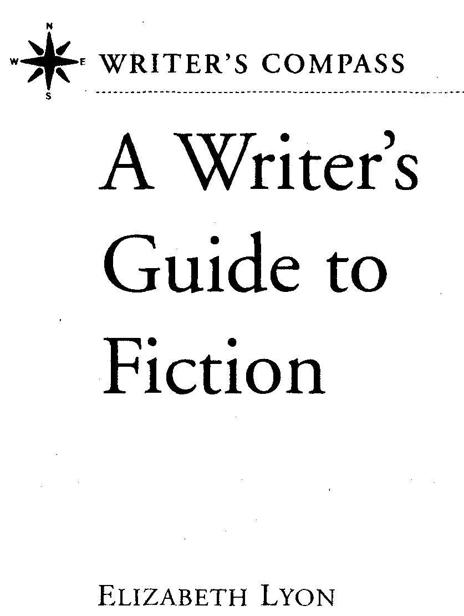

CONTENTS

NORTH:

Getting Your Bearings

1. The Lay of the Land

2. Finding the Characters for Your Story

3. Finding a Map for Your Story

4. Heroes and Heroines

5. First Steps

6. Deepening Your Characters

7. Casting Characters for Story and Plot

8. Mapping from A to B to Z

Narration and Visuals: Setting, Description, and Imagery

Finding Your Gait

11. Ending Steps

SOUTH:

Troubleshooting and Problem-Solving

12. Problems of Characterization, Structure, Technique, and Style

EAST:

Your Rising Star

13. Learning to Market

WEST:

Refining Your Vision

14. New Horizons

|

I believe that stories have this powerthey enter us, transport us, they change things inside us, so invisibly, so minutely, that sometimes, we're not even aware that we come out of a great , book as a different person from the person we were when we began reading it. Julia Alvarez |

T HE MOMENT YOU lay down your first words of fiction, you become a magician like David Copperfield. Through the alchemy of craft and story, you create an illusion where the reader suspends disbelief, just as Copperfield makes his audiences believe he's made a Boeing 747 airplane disappear.

Modern neuroscientists have discovered what ancient shamans have known all along: Stories have power. Power to heal, to destroy, and to change history. In fact, fiction may have a longer-lasting effect than magic. Thought releases brain chemicals and neural electricity. Stories can "get under the skin" and integrate into the interior landscape of the selfand perhaps of the soul.

We writers receive no greater compliment than to have our readers lament the ending of a story. Imagine how you would feel knowing that your characterstheir lives, dilemmas, and triumphslive on in the memory of your readers side by side with memories of actual people and situations.

Stories move people to think and act. Anai's Nin said, "What we are familiar with we cease to see. The write shakes up the familiar scene, and as if by magic, we see a new meaning in it." Art, in the form of a story well told, may literally transform the reader and the culture from the inside out. "A book ought to be an ice pick to break up the frozen sea within us," said Franz Kafka. Stories hold the power to transform the very society they are said to reflect, making storytelling among the highest of callings.

The Language of Fiction

Some writers may consider the distinctions between situation and story, plot and story, and promise and theme as splitting hairs. However, understanding the language of craft and how it operates in the creation of fiction is as important as a musician learning to read notes and play scales. Incident, situation, plot, story, protagonist, antagonist, promise, and theme all establish the foundation upon which you can build any story you might want to write. Before we go any further, let's define some of these important ideas.

STORY AND PLOT

The child tucked into bed asks her mother, "Will you tell me a story?" The mother reads "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" or "Hansel and Gretel," or perhaps the mother makes up a character and story, as many parents do. We all grow up with a sense of story, but what, in a technical sense, does story mean to a writer?

In this book, story means the deepest meaning of a tale, while plot refers to the characters and the events that fulfill the story in a specific way. Story is deep; plot is mechanical, even if it is complex. Story is universal; plot is particular. Snow White and her friends, the dwarves, interact in a plot that demonstrates a story about trust. Hansel and Gretel experience a number of incidents that demonstrate a story about adversity and survival.

Many beginning fiction writers create characters who act and are acted upon, but in the end, they have no story. They have a set of incidents that make up a plot. This is no surprise when you think about it. It's one thing to watch a magic trick that looks so easy; it's another to carry it off yourself.

For instance, my friend Betty and I take Riley, my Border collie, on a walk. She and I discuss going to a movie on Wednesday night. I glance down the path and recognize an old boyfriend. As we greet each other, Riley chases a squirrel. After awhile, Betty and I finish our walk and return home.

Is this a story? No. Is it a plot? No. What I have shared is a situation and some incidents. Daily life is filled with as many incidents as you care to identify: getting dressed, going to work, talking with friends. All kinds of situations arise from the incidents of our lives. They range from the walk with my friend and dog to someone cutting you off in traffic to an unexpected checkor billarriving in the mail.

A situation can become a plot once you have someone with a problem or conflict who seeks an outcome to resolve it. Let's revisit my situation with the many incidents.

I go for a walk with Betty because I am lonely. I ask her if she wants to see a movie on Wednesday night, but she's busy. We encounter my old boyfriend John and stop to talk. Betty knows I was crushed when he stopped seeing me because I wasn't "the one." He is obviously taken by Betty, and by the end of the conversation, he asks for her phone number..While I'm busy chasing Riley, who has run after a squirrel, John asks Betty to go to a movie on Wednesday night. Betty looks my way, then turns to him and says, "Sure."

What I've described here is a plot. You have a character with a problem. She's lonely and seeks her friend's company. She pursues a solutionsharing a movie. You have opposition to her attempt to resolve her problemher friend can't go. You have a further complication when the old flame makes her loneliness deeper by show-

Story is deep; plot is mechanical.

Story is universal; plot is particular.

deeper emotional context of loneliness and the yearning for human companionship, along with the acceptance and caring that friendship implies, it became a story. Are you wondering what happens next? If so, I've begun making magic. You have, at least partly, suspended disbelief in the fictitious world and through curiosity, have shown your willingness to pretend my story is real. Why have you done this? I would bet that you, too, have experienced times of loneliness, the need for human companionship, and the comfort of belonging through friendship. These are universal human needs. You can relate vicariously because my story is your story.

Will you be transformed? Will you carry away some nugget of realization or learning that will transcend this particular story? Currently, I've left you midstream, in the middle of the conflict. The end of the story would determine what the main character learned. Told artfully, a story can move you and alter your brain chemistry. You might make different choices in your life as a result. By my story, not by my plot, you might be transformed.

CHARACTER

Most stories have two levels: the external plot events and the internal character need. Both levels culminate in the characterand reader learning something fundamental about self and life. Inner and outer; outer a reflection of inner. The oft-repeated reference to a character-driven plot refers to the inner story about character that always underlies and propels the outer plot events. Characterization, not plot, is the core of successful fiction. Characterization, not plot, is the source of a writer's greatest magic.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A writers guide to fiction»

Look at similar books to A writers guide to fiction. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A writers guide to fiction and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.