Contents

Acknowledgments

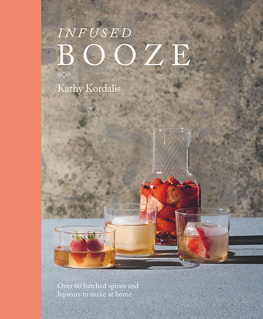

I never realized what a lazy writer I could be until I started testing inebriants. Working on this book has been a blast for me but, I fear, a slog for the editors, designers, agents, and publisher forced to whip me into meeting my deadlines. If you appreciate this book at all, you are as indebted to their diligence as I am. They are Lisa Ekus, book agent; Margaret Sutherland, acquiring editor; and most of all Lisa Hiley, the editor and superego of everything you see before you. Thanks also to Valerie Cimino, who copy- edited the text, Jessica Armstrong, who designed the pages, and Leigh Beisch and Dan Becker, the photographer and photo stylist, who found innumerable props and compositions to make a glass and a bottle of booze look scrumptious every time.

Preface

Of all the potent potables that one can brew at home, liqueurs are the fastest, easiest, and most versatile. Liqueurs are liquors (distilled spirits) that have been flavored with sugar and aromatics, such as herbs, spices, nuts, flowers, fruits, seeds, vegetables, roots, and/or bark.

The practice of infusing alcohol with other ingredients began as a way of making herbal medicines. Cordials were liqueurs that stimulated circulation the word cordial comes from the Latin cor, meaning heart.

The same chemical properties that give alcohol the ability to bind with medicinal elements in herbs and spices also make it bind with tastes and aromas. By the fifteenth century, liqueurs had moved from the pharmacy to the dining room, where they were served to enhance food. Liqueurs served before eating (aperitifs) set up the appetite for the main courses to come. Those served after the meal (digestifs) helped one digest what had already been consumed.

Liqueurs can be flavored by soaking flavorful ingredients in already distilled alcohol, a process known as tincturing, or by distilling them along with the alcohol. Those made by tincture are easier to fabricate and tend to be sweeter and more viscous than those that are made by distilling the flavorings and alcohol together. The tincture method is not only the easier of the two; currently it is the only method that is legal in North America.

The popularity of home-brewing beer and wine has given rise to an interest in artisan moonshining (home distilling). New Zealand repealed its ban on home distillation in 1996, and distillation for home use is not outlawed in countries that have a long cultural history of small scale home-based artisan stills, like Italy and Ukraine, but in the United States and Canada, distilling without a license is still illegal. (HR Bill 3949, introduced in the 110th Congress on October 23, 2007, by Representative Bart Stupak of Michigan, attempted to amend the Internal Revenue Code to repeal the prohibition on producing distilled spirits in specified locations, including dwelling houses and enclosed areas connected with any dwelling house. The bill died in committee.)

Homebrewing and winemaking require a laboratory of equipment, a repertoire of special skills, and weeks to years of time and patience to produce something drinkable not so liqueurs. A modestly equipped kitchen provides all of the tools necessary for making almost any liqueur, and provided your interest is centered on fabricating libation, rather than medication, most any liqueur can be made in a matter of days, and some as quickly as a few hours.

Part 1

The Basics

Homemade Liqueurs & Tasteful Spirits

Flavoring alcohol is straightforward. Most liqueurs use neutral grain alcohol, such as vodka, as a base, although I use a variety of bases, including rum, tequila, whiskey, vermouth, and wine. The process of infusing such nonvolatile substances as iodine into alcohol in the preparation of medications is known as tincturing. Even though liqueurs are no longer considered medicinal, I find it clarifying to use this somewhat archaic term to describe the process of flavoring spirits.

To make a tincture, the flavoring ingredients are broken or cut into small pieces to expose more surface area to the alcohol, and sometimes sugar syrup is added with them. I have found that adding sugar in the initial stages of tincturing slows down the transfer of flavorful components into the alcohol. So when using a flavorful sugar such as brown sugar, agave, jaggery, or honey, which has aromatic elements that need to infuse into the liquor base, I add the sweetener in the first step, but when using unflavored sugar syrup made from granulated white sugar, I add the sugar after the initial tincturing is complete.

When the flavoring ingredients are combined with the alcohol, the chemical power of alcohol takes over. Alcohol bonds with both water-soluble and fat-soluble molecules, which gives it awesome power to attract and hold on to any flavor molecules. Those flavors perceived on the tongue (salty, sweet, sour, bitter, and umami) are soluble in water, while all other flavors (herbal, fruity, spicy, floral, garlicky, and so on) are fat soluble and perceived through the nose. When you are flavoring a recipe, your cooking medium largely determines what flavors emerge. Boil garlic in water and the results are largely sweet. Saut the same amount of garlic in oil and the sugars are unnoticeable, but the garlicky pungency can be overwhelming. But soak a flavorful ingredient in alcohol and the solubility of its flavorful components doesnt matter: Everything ends up in the booze.

Different ingredients take more or less time to infuse their flavors into an alcohol base. The timing depends on several factors:

- The proof (alcohol percentage) of the base spirit

- The concentration of flavorful components in the blend

- The volatility of the flavorful components

Basic Booze Vocabulary

Alcohol by volume (ABV). Percentage of alcohol in a solution in volume measure

Brew. To prepare beer by steeping or infusing water with grains and hops and fermenting the resulting mash

Distill. To vaporize a liquid, such as alcohol, and cool the resulting gas to precipitate a purer form of the liquid

Ferment. To convert sugar into carbon dioxide and alcohol using yeast

Infuse. To permeate a fluid with elements from a solid material

Liqueur. A flavorful sweet distilled spirit

Liquor. An alcoholic beverage

Proof. A numerical description of the percentage of alcohol in a liquid equal to about half of the actual ABV

Steep. To infuse in water

Tincture. To infuse in alcohol

Proof. The concept of proof developed in the eighteenth century, when British sailors were paid partly in rum. To ensure that the rum had not been watered down, it was proved to be undiluted by dousing gunpowder with the liquor, then testing to see if the gunpowder would ignite. If it wouldnt, the alcohol content was considered too low, or underproof. A proven solution was defined as 100 degrees proof, because it was assumed that it did not contain any water.