The New Yorker magazine ran an interview with a cove called Lemuel Benedict now that is a proper New York name. He took a monster hangover to The Waldorf and ordered hot buttered toast, crisp bacon, two poached eggs and a hooker of hollandaise. The chef was intrigued, substituted English muffin for toast, Canadian bacon (back) for crisp (streaky) and there you are: a legend was born. This is how cooks make food: they see something, taste something, and then tinker with it

A.A. GILL, BREAKFAST AT THE WOLSELEY

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe

JOHN MUIR, MY FIRST SUMMER IN THE SIERRA

Foreword

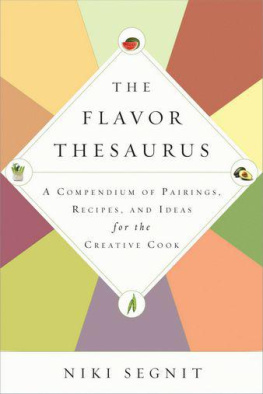

There is only a handful of books that end up becoming handbooks in my ideal sense of the word: a bound companion I keep on hand, always ready for use; an undisputed, dependable voice of authority on a subject close to my heart. The Flavour Thesaurus, Niki Segnits first book, is my handbook for pairing flavours.

I received my copy from a friend in 2010. After a quick run-through and an initial feeling of awe at the chutzpah of the endeavour, I sat down and read. I read it cover-to-cover and could not believe my luck. Someone had just handed me the equivalent of the Rubiks cube solution booklet I had as a child only this one held the solution for every kitchen puzzle imaginable!

As a chef and a cookery writer, my job is to endlessly test flavour combinations. I do this in my head, I do this in saucepans and roasting trays, I do this in soup bowls and glass tumblers, and I do it on the tip of my tongue. The Flavour Thesaurus is, really, the only tool that allows me to test some of my assumptions without having to turn on the stove. Will aniseed work with pineapple? Let me ask Niki. Should I add parsnip to my fish stew? Ill just flick through my little handbook here.

Yet what I find immensely gratifying is not the few minutes shaved off aimless straying on the way to a dish, but the sense of encouragement and reassurance that I am on the right track, that my thoughts are reasonable and well-grounded. In her writing, Niki Segnit brings together a towering edifice of cooks, food writers and experts to inspire the utmost confidence. And even as she presents their weightier points, she makes absolutely sure no one falls asleep. Chuckling away whilst reading a book about food is not something that happens to me very often; its a regular occurrence with either of Segnits books on my lap.

Heres a wonderful example from Lateral Cooking: Broth is a stock with benefits the ingredients that create it are eaten rather than discarded. Pot au feu is a good basic example. Its a poem of the French soul, according to Daniel Boulud, and one that takes a good while to compose. Marlene Dietrich liked to make it in the lulls between scenes. It doesnt, however, require a lot of attention, so therell be plenty of time to run your lines and pluck your eyebrows. Who wouldnt be seduced by the Boulud-Dietrich-Segnit trio?

The point I am making is serious, though. What is so compelling about the world of Niki Segnit is the way she takes her phenomenal body of work based, no doubt, on long days spent in reading rooms with heaps of scholarly texts and then deftly weaves in personal stories and anecdotes. Humour is an essential element, as is the sensuality of eating, lest anyone get the wrong impression about this particular thesaurus.

Her distinctively relaxed style, combined with a clever, schematic way of breaking down a vast subject into palatable though not always bite-size pieces is carried through with great panache to Lateral Cooking. In the same way as our food experiences were deconstructed in her first book, giving us clarity of the crystally kind and lots of a-ha moments, her second book examines our food activities and shows how magically interconnected they all are. By exposing the relatedness of one cooking technique to another, and of one dish to the next, it uncovers the very syntax of cookery.

As a cookery writer, I have to admit, I am pretty jealous of this achievement. It shows a depth of understanding and a degree of insight that I probably couldnt ever master. But what I am far more resentful of is the fact that Segnit has managed to fulfil one of my deepest, nerdiest fantasies. When writing recipes, I find it almost impossible to accept the moment at which I need to stop testing. It simply kills me every time Im forced to lay to rest all the variations that havent been tried, the potential masterpieces that will have eluded me if I dont explore one final option. Its the culinary equivalent of FOMO, the Fear of Missing Out that epitomises the angst of our age.

Lateral Cooking is devoid of any such anxieties because it is a cookbook full of open-ended recipes. On top of the official version, Segnit offers a bunch of Leeways, to use her term. These keep the recipes alive; they grant us freedom to experiment, given confidence by the rich toolkit Segnit generously equips us with. So a simple loaf of bread, for example, can have a third of the flour in it replaced with the same weight of warm apple pure which, when baked, fills the room with the aroma of apple fritters. Who on earth would be happy with a boring old standard loaf after reading this? And if apples, why not quinces? Or apricots? Or even courgettes?

It takes a person with a particular kind of knowledge to open up a whole load of roads-not-taken for those of us who are keen on going on a journey of exploration: knowing how to write whimsically, cleverly, confidently and yet modestly; knowing how to cook; knowing how to inform and not bore; knowing how to entertain and tickle; knowing how to enchant and enrapture the imagination. These are the writers qualities that have brought about another handbook one for imaginative cooking.

YOTAM OTTOLENGHI

Learning to Cook Sideways

My maternal grandmother cooked everything from scratch and by heart that is, with an assessing eye, an experienced touch and absolutely no recourse to written instruction whatsoever. What would she have made of the shelves in my kitchen? Theres Anna, Claudia, Delia, Fuchsia, Madhur, Marcella, Nigel, Nigella and Yotam. Theres The Fruit Book, The Vegetable Book, The Mustard Book, The Yogurt Book and The River Cottage Meat Book. Theres How to Cook, How to Eat, What to Eat and What to Eat Now. And yet for years the size of my library was inversely proportional to my confidence in cooking from it. I could cook something a dozen times and still have to dig out the recipe. When I did, I conformed to the image of the Stepford cook: obedient to the point of OCD. If a recipe called for one teaspoon of water, I would lean level with the tap and fill a teaspoon precisely to the brim, discarding it and starting again if the spoon overflowed and left me millimetrically shy of the measure.

In my defence, my grandmothers culinary horizons were narrower than my own. Her repertoire comprised, perhaps, a few dozen classic British dishes, seasonally adapted. What lurked beneath the crust of her crumble depended on what fruit was available: rhubarb stalks from under their upended bucket, or apples from any of the six varieties she grew in her tiny back garden. Over the course of my childhood and adolescence, Indian, Thai and Chinese food were added to the melting pot of British cuisine, or at least British culinary competence, on top of the French, Italian and Spanish classics mastered by my mothers generation. Now keen cooks can buy Japanese nori and sushi rolling mats in their local supermarket. Hawaiian