Life and Food in

the Basque Country

Life and Food in

the Basque Country

Mara Jos Sevilla

NEW AMSTERDAM BOOKS

4720 Boston Way

Lanham, MD 20706

Copyright 1989 by Mara Jos Sevilla

All rights reserved.

First published in the United States in 1990 by

New Amsterdam Books

by arrangement with Weidenfeld & Nicolson, Ltd., London.

All illustrations by Clifford Harper.

Translated from Spanish by Juliet Greenall.

ISBN: 978-1-56131-035-7

Printed in the United States of America.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

CONTENTS

The market tradition the tapas bar tejas and the cake shop the butcher vegetables and menestra Francisco Gainza, the mushroom seller scrambled eggs with zizak beans from the New World cooking with salt-cod Jos Martin the shepherd and cheesemaker intzaursalsa, walnut and cinnamon cream

Life on a farm the kitchen garden Cndidas daily-round beans and other home-grown vegetables family meals and lengua a la tolosana winter compote Basque peasant cooking pickled chillies farmhouse cider omelettes pig-killing day chorizo the pleasures of self-sufficiency

Ondrroa anchovy and sardine fishing costera del bonito preparing tunny and salt-cod the summer fiestas and marmitakobuuelos, custard fritters the canning industry bream and tunny fishing red mullet pesca de altura life at sea the women at home fishing today

The lure of the valley Domingo, the kaiku-maker Domingos wife and cheesemaking the workshop birch tree felling making a kaikumamia with fruit cheesemaking talos shepherds dishes carnival time pigeon-trapping and game dishes witchcraft the village inn traditional roast lamb

The sidreras: Basque sociability probateko or tastings fueros and the local laws the city cider houses vats and cider-making an evenings entertainment the bodegas: Pedro Chuecas wine education cultivating the vines cooking with txakol the disappearance of the caserios-txakolasadores and grilled fish

The oldest street in San Sebastin Kika Belandias family pastelitos de fruta weekend meals and sopa de pescado shopping in La Brecha market the competition of the supermarkets cocido and chickpea recipes Jos Ramons delicacy, crayfish a social life Carnival celebrations at Tolosa

Luciano Belandia, society cook admittance to the sociedades their origins in the War of Independence idiosyncratic cooks Lucianos specialities sporting activities the secret of scrambled eggs todays cooks pimientos tapas male dominance fruit dishes and tocinos de cielo the Tamborrada, a culinary fiesta

The renaissance of Basque cooking a love of good food Pedros restaurant shopping and preparing a menu cocina marinera and shellfish dishes nueva cocina vascalubina a la pimienta verde duck-russulas fig and walnut millefeuille

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Life and Food of the Basque Country began at the Oxford Food Symposium in 1987 when I was talking to Vicky Hayward about a theme which for years has occupied the majority of my free and professional time: the people of my country, their food and drink and in particular their gastronomic culture. Without Vickys encouragement and enthusiasm this book would probably never have been written.

While the Basques character and respect for tradition has always attracted me, their generosity has proved to be overwhelming. My gratitude to Pedro, Kika, Patxi, Asensio, Milagros, Antonio, Joseba, the Lasa family, Domingo, Nunchi, and to all who have so actively contributed to the reality of the chapters which follow. The linguistic ability of Juliet Greenall and Suzannah Gough and the patience of Philip, Daniel and Angeles have proved invaluable.

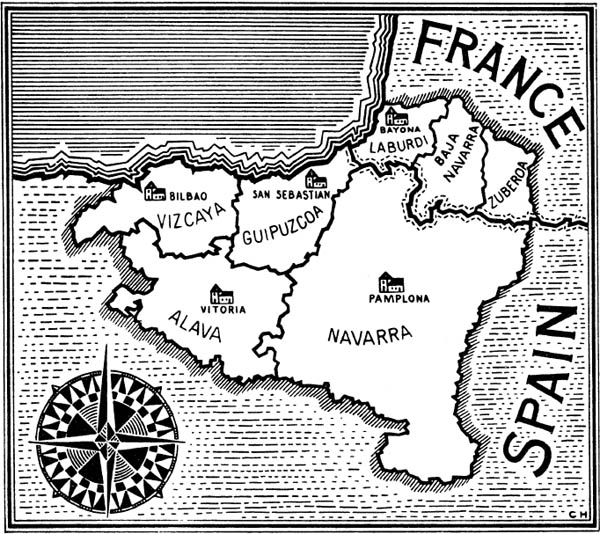

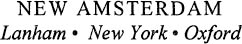

The Basque Country

INTRODUCTION

Who are the Basques: where do they live; what language do they speak? Where does their passion for action and freedom, their staunch individuality and, above all, their love of good food come from? What today is known as the Basque Country, or Euskadi, consists of the provinces of Baja Navarra, Labourdie and Zuberoa on French soil and Alava, Guipzcoa, Vizcaya and Navarra in Spain.

The Basques have always been seen by the other inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula as rather brusque, with great sincerity and strength of character, with an unswerving attachment to tradition, deeply religious, and with an obvious seafaring vocation. The novelist, Pio Baroja, wrote: I cannot define the Basque character concisely; all that I can say is that most of them have a warlike streak, that nearly all those who inhabit the countryside are slow of understanding, and that they are men of few words, who are rarely idle; calm, thoughtful and silent.

The land where they have lived since prehistoric times lies either side of the western end of the Pyrenees, both inland and along the coast washed by the waters of the Cantabrian Sea. As you travel from Castile into the Basque Country villages, clustered around churches as though in search of shade, begin to stretch out along a single street, until eventually they become completely isolated farmsteads. The contrasting landscapes are sometimes calm and tranquil: the wheatfields of Alava, the maize plantations of Guipzcoa, picturesque little fishing villages; at other times they are harsh and moody with a series of cliffs or mountain-peaks, partially clothed in luxuriant, leafy beechwoods, and with barren crags showing the harsh limestone rock at its most beautiful and unyielding; it changes mood dramatically according to the capricious and unpredictable climate. Hours of calm and blue skies may suddenly give way to unexpected and noisy storms when thunder and lightning rage furiously, the wind roars and the sound of the leaves as they rustle against each other is like an angry sea.

According to Father Barandiarn, one of the great experts on Basque matters, this is a culture which goes back 50,000 years. For his part, the ethnologist, Julio Caro Baroja, feels that one cannot speak of the Basque Race since, apparently, up to the present-day all attempts to clarify the origins of such a race have proved useless and are lacking in scientific rigour. On the other hand, Baroja maintains that it is possible to speak of a Basque Tongue in his view an obvious survival of languages which predate the Indo-European invasion and, according to him whose form may have changed, but which survives. The same author believes that the Basque language is related to that of the Aquitaine of south-west France.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.