Contents

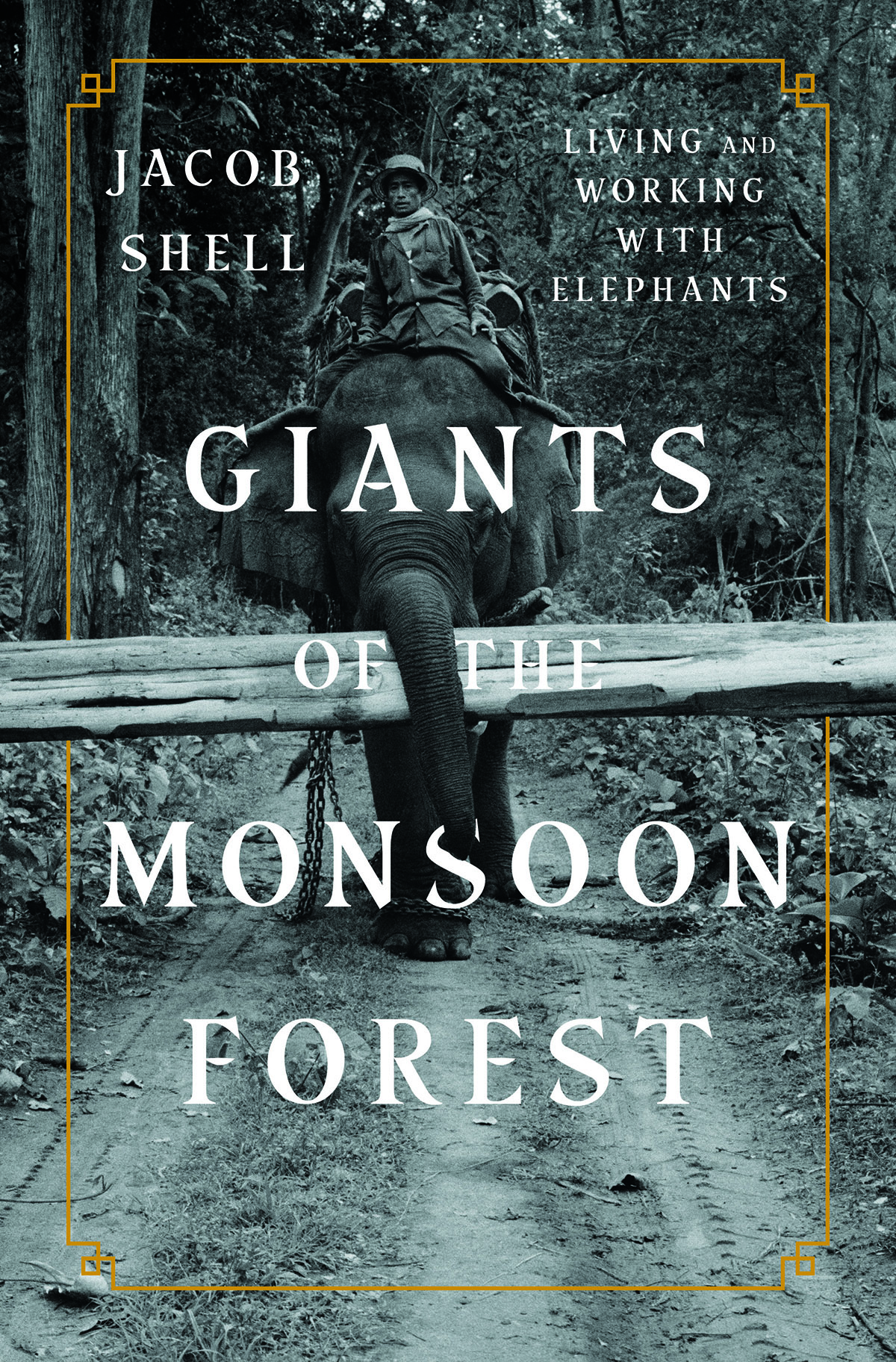

GIANTS

OF THE

MONSOON

FOREST

Living and Working

with Elephants

JACOB SHELL

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

NEW YORK LONDON

Giants of the Monsoon Forest is a work of nonfiction.

Certain names and potentially identifying details have been changed.

Copyright 2019 by Jacob Shell

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Lovedog Studio

Production manager: Lauren Abbate

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Shell, Jacob, 1983 author.

Title: Giants of the monsoon forest : living and working

with elephants / Jacob Shell.

Description: First edition. | New York : W. W. Norton & Company,

[2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018058217 | ISBN 9780393247763 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Elephants. | Human-animal relationships.

Classification: LCC QL795.E4 S525 2019 | DDC 599.67dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018058217

ISBN 9780393247770 (eBook)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

For my grandparents

CONTENTS

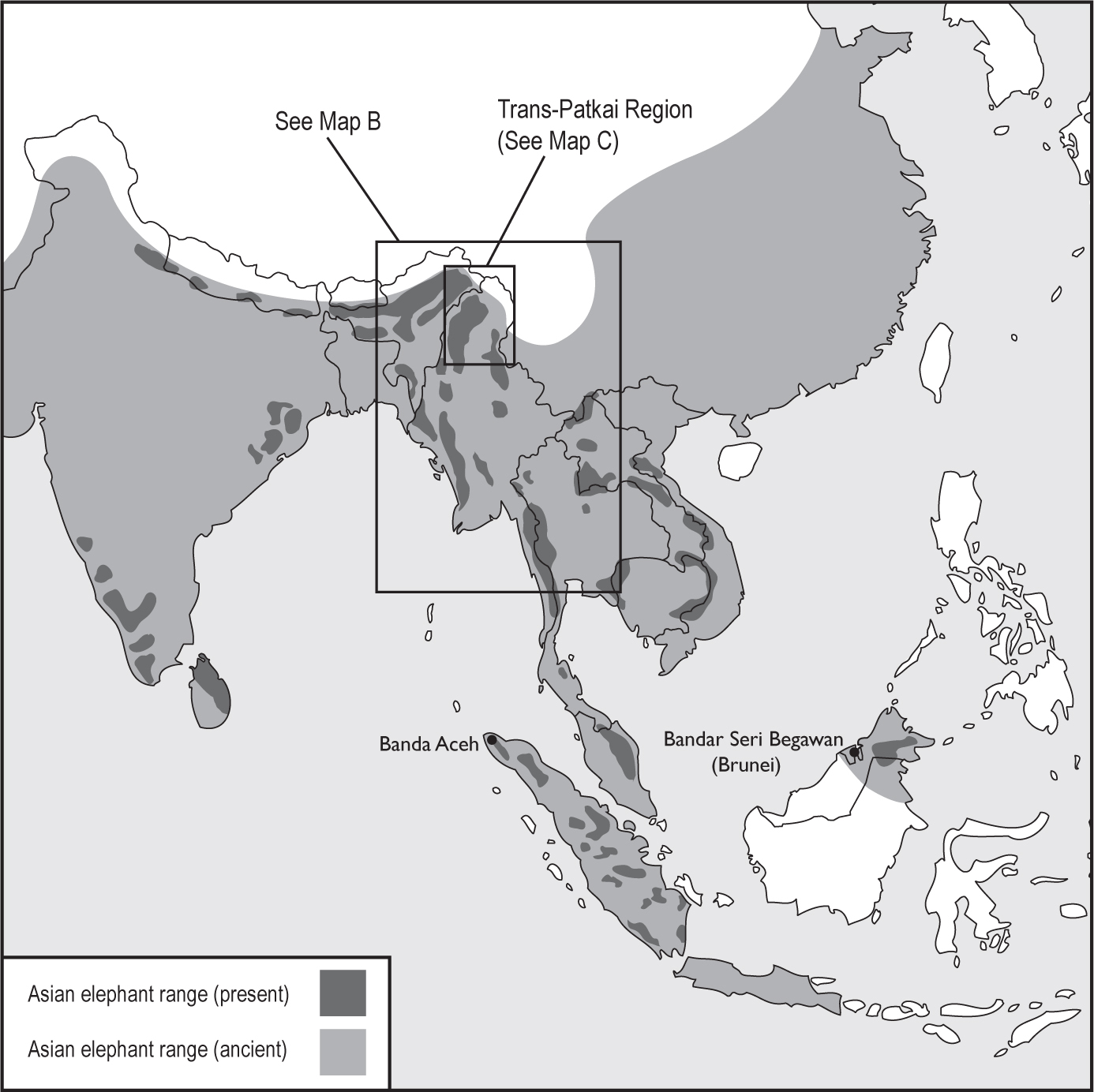

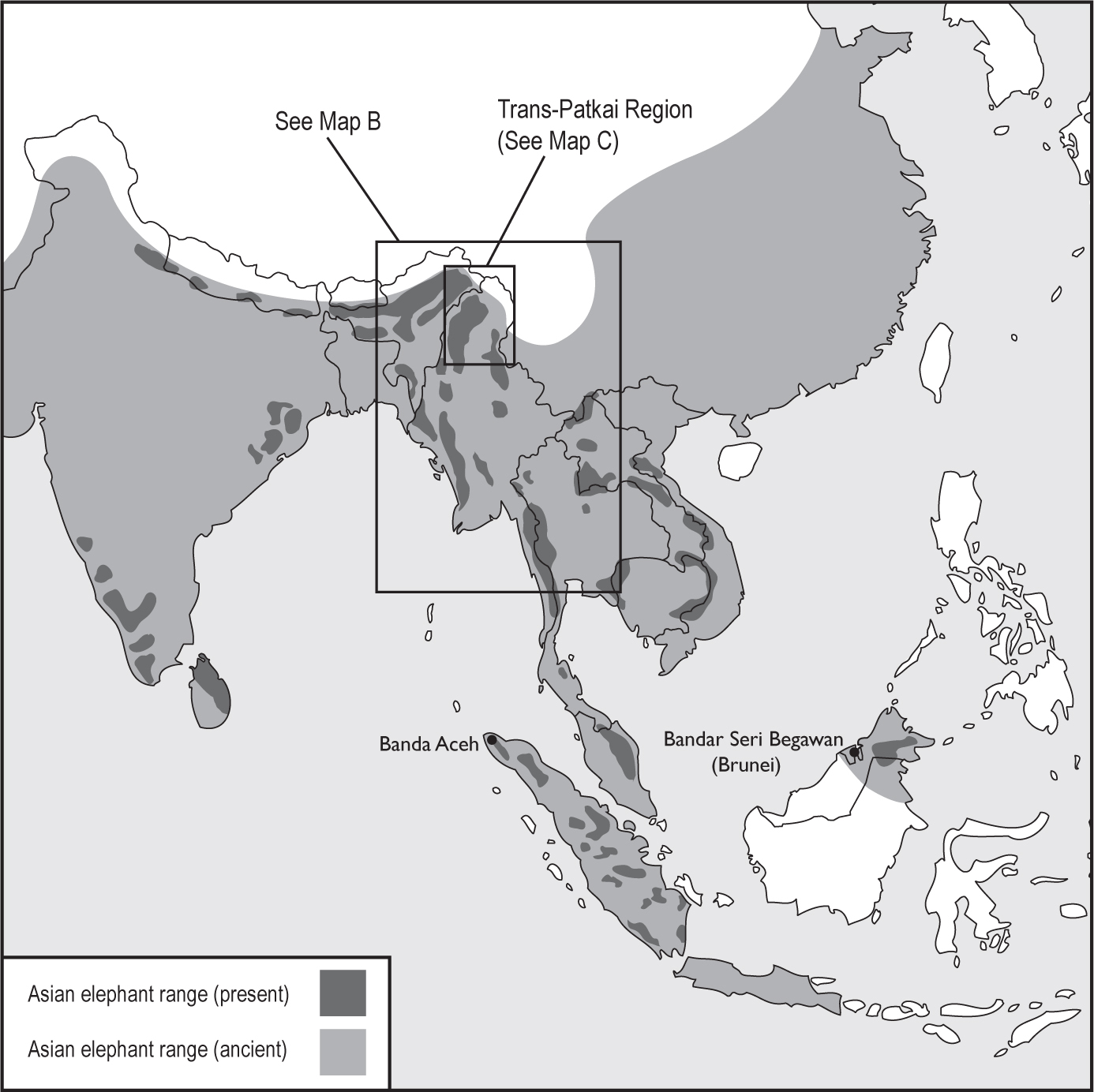

Map A. Present and ancient ranges of the Asian elephant

(Elephas maximus) in South and Southeast Asia.

Cartography by Jacob Shell.

Map B. Central and Upper Burma (Myanmar).

Cartography by Jacob Shell.

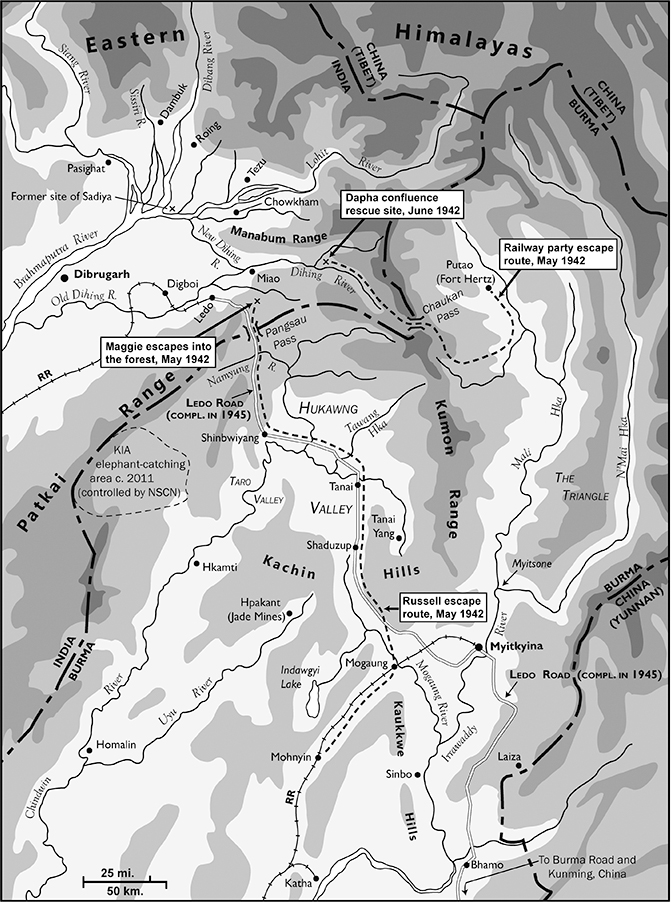

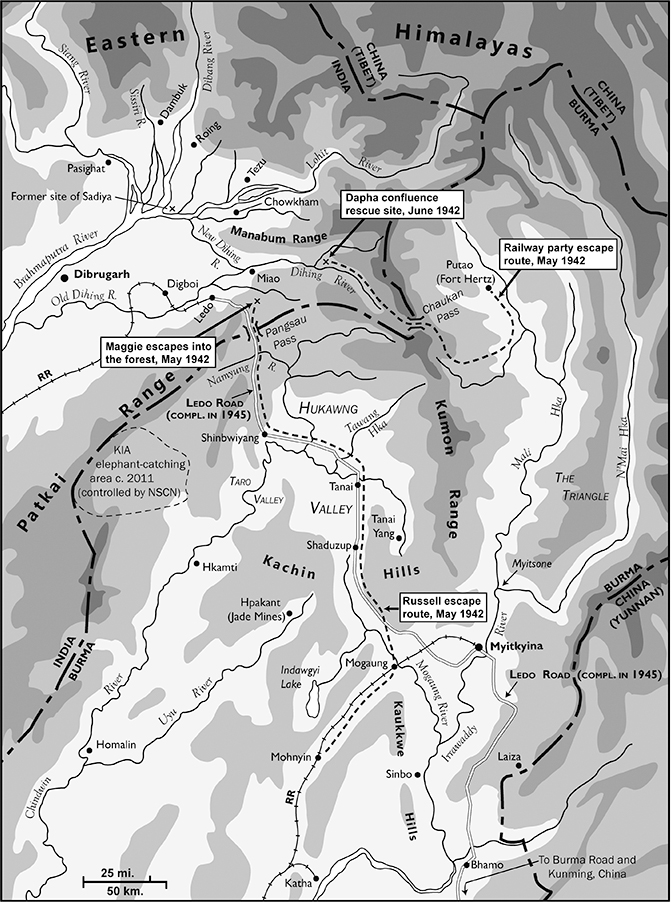

Map C. The Trans-Patkai region. The map shows the

railway party and Russell party escape routes during

World War II. Cartography by Jacob Shell.

I AM A GEOGRAPHER BY TRAINING; THIS MEANS, SO I persuade myself, that I should pay close attention to those places that do not show up in todays atlases and maps. Among these places are the tangles of elephant trails that wind their way through the remote forestlands between India and Burma. Pensive giants traverse these trails with humans perched on their broad necks and backs. The routes they follow have a secluded and untraceable qualityshifting their position in seasonal cycles, inaccessible for motor vehicles, hidden from satellite view by tree canopy and monsoon clouds. If contemporary maps are to be believed, the elephant trails stopped existing once modern cartographers traded in their boots and mosquito nets for software manuals and subscriptions to satellite imagery databases. But contemporary maps are not always to be believed. The trails are still there. So are the trained elephants who tread these paths, carrying their riders, who are called mahouts in English (a loanword from Hindi) and oozies in Burmese.

I visited that sylvan country, in the shadow of the peaks where the green Patkai Mountains meet the precipitous white blockade of the eastern Himalayas, over the course of several trips during the mid-2010s. I always went to meet the working elephants and the mahouts who know them best, and to learn about the trails that elephant and mahout follow into the obscurities of the forest. On my first trip like this, in 2013, I visited a hillside village in Burma (also known as Myanmar) whose human inhabitants lived in bamboo huts, their work elephants thundering about the jungle by night and hauling great teak logs by day. The monsoon season was just breaking, and the tropical landscape teemed with creatures who dwell in some intermediate state of matter, something between water, air, and earth. One day I was coming down a rain-soaked path by the village and my boots became stuck in the thick, viscous mud. As I paused to poke the sludge away with a stick, I was startled by a strange skipping snake that hopped by like a rabbit, bouncing from the ground into the air in fast three-foot hurdles, then gliding back into the mud from whence it came. At night torqueing clouds of white flying insects arose from the spongy earth, seemingly hatched by the pattering of the constant rain. Some swirled through the falling droplets with goblin-like delight, while others crawled frantically along the solid matter of the bamboo human shelters, determined to get inside. During another trip, in a village at the base of the eastern Himalayas, I saw frogs hop along water surfaces like skimming stones. They went eight, ten hops at a time as if the liquid surface of a river were sturdy as rock, submerging only when they felt provoked into aquatic hiding.

From this green backcountry, where earthly elements blend together during monsoon, emerge the headwaters of the Irrawaddy River, Burmas largest watercourse, as well as the upper reaches of the Brahmaputra, the Mekong, and the Yangtzethe great river systems of India, Southeast Asia, and China. These uplands have traditionally been a kind of no-mans-land at the outermost margins of the various kingdoms and empires that dominate the fertile river valleys. The discharge of monsoon rains helps hold the lowland powers at bay, combining with glacial melt from the Himalayas to inundate mountain vales, rearrange local watercourses, obliterate bridges, and obstruct highways with sudden landslides. Wheeled vehicles of all kinds become stuck fast in the mud and mire, as do the hooves of horses and mules. Boats and river rafts, though sometimes useful, are blocked by debris: felled trees, boulders, and silt.

The elephants, by contrast, thrive in these dynamic conditionsin the constant flux between sand, mud, and mist. At certain times of year, and for people doing certain kinds of work, the elephants are the best way of getting around. Trained elephants have comprised the centerpiece of the Burmese teak-logging industry up through the 2010s. At the turn of the millennium, this industry produced nearly 70 percent of the worlds internationally traded teak woodmuch of it felled, skidded, and then carefully arranged into neat piles by elephants ridden by their mahouts in the Burmese jungle.

The elephants go where the roads cannot. The ease and skill with which they move across monsoon-soaked landscapes has made them optimal transportation during floods. In one famous incident during World War II, elephant convoys from Assam, a state in northeastern India near Burma, rescued hundreds of Indian, Burmese, and British refugees trapped at an upland river confluence near the Burma-India border. The area had flooded during heavy rains and was unreachable by boat, train, or truck. The British officers charged with running the operation took movie cameras with them; footage of the remarkable emergency relief elephants shows the animals and their mahouts fording a torrent of white-capped floodwaters on the approach to the refugees camp. More recently, following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, elephants assisted in cleanup efforts in northern Sumatra and southwestern Thailand, where the damage to local road infrastructure was so severe that jeeps and trucks could not be used.