Table of Contents

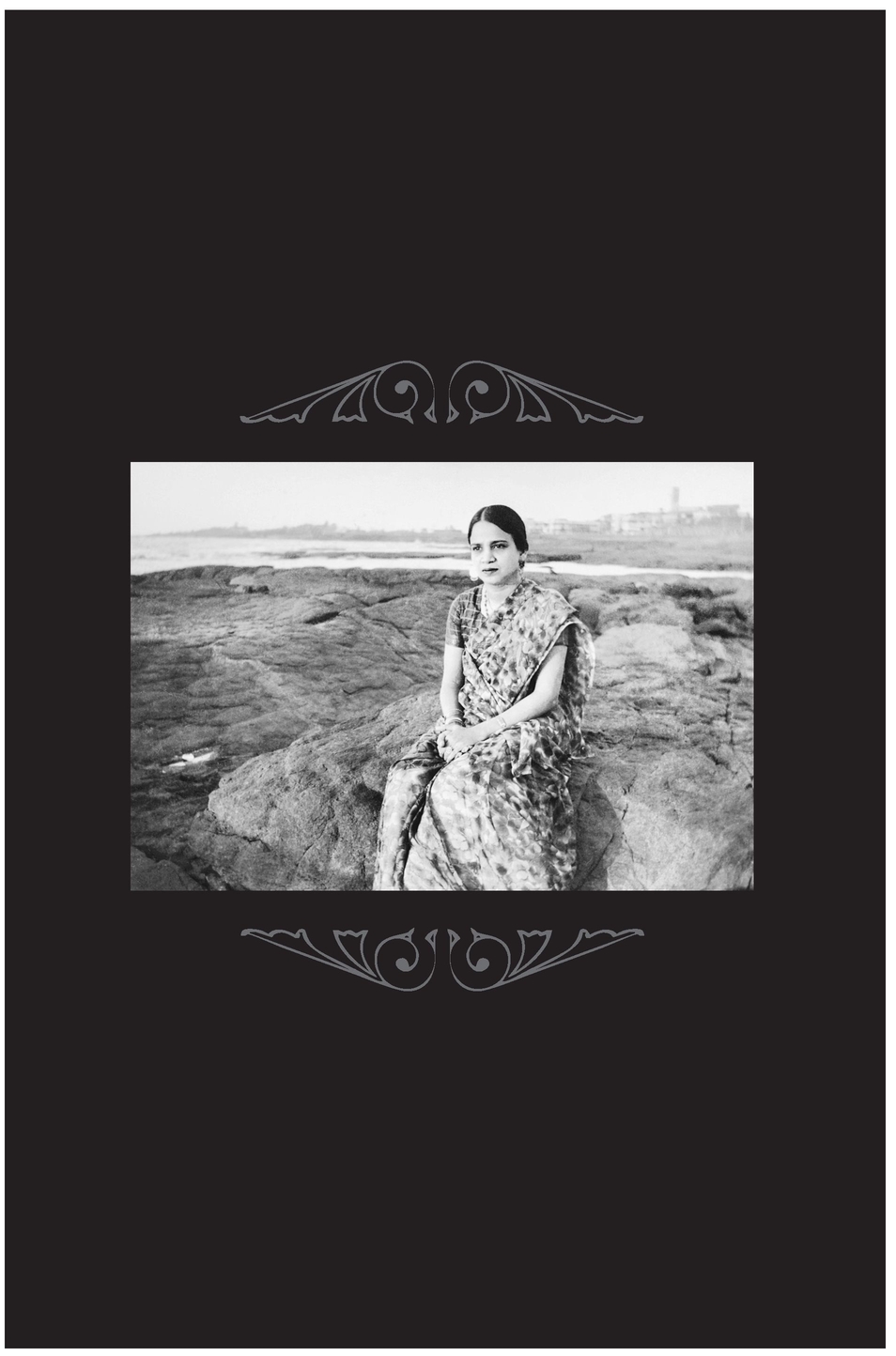

For Nana

When I think of Bombay now, at this distance of time, I seem to have a kaleidoscope at my eye; and I hear the clash of the glass bits as the splendid figures change, and fall apart, and flash into new forms, figure after figure, and with the birth of each new form I feel my skin crinkle and my nerve-web tingle with a new thrill of wonder and delight. These remembered pictures float past me in a series of contrasts; following the same order always, and always whirling by and disappearing with the swiftness of a dream, leaving me with the sense that the actuality was the experience of an hour, at most, whereas it really covered days, I think.

Following the Equator, MARK TWAIN

And might it not be, continued Austerlitz, that we also have appointments to keep in the past, in what has gone before and is for the most part extinguished, and must go there in search of places and people who have some connection with us on the far side of time, so to speak?

Austerlitz, W. G. SEBALD

PROLOGUE

ARRIVAL

It is the sounds we hear as children that shape us.

It is the snap-crush of spices under the heel of my grandmothers hand. It is the slip-splash of her fingertips, sliding fish into turmeric water. It is the thwack of her palms, clapping chapattis into life on her flat stone, a perfect circle, every time. It is the swish of her sari, the click of her knitting needles, the tap-tap of the soles of her feet hitting the soles of her sandals. There lies my grandmothers Morse code.

Her voice is quiet and fierce as she braids my long hair, telling me fragments of stories, pieces of her life in India. In my childs ears she whispers her dreamsstrange, frightening dreams that have come to her in sleep since she was a child, predicting every death in our family. She weaves these dreams and these stories into my braids. They are mine now, tied with red ribbons.

Listen carefully. These are the sounds of my house.

Downstairs my father is teaching my six-year-old brother, Cassim, to ride a bicycle in the driveway. Cassim is too small; he is falling off the bike and laughing; my father is calling out to him to look straight ahead, dont look down, there you have it. Stay straight! Stay on the driveway! My mother is in the kitchen, talking on the telephone to her brothers in Pakistan. It is afternoon in Boston, the middle of the night in Karachi; she is shouting in Urdu to be heard across the distance. Ill be arriving on the sixteenth of next month! What do you need from here? Send the driver to the airport!

YEARS LATER, I visit Bombay as an adult, and the city seems strangely familiar, like the end of an interrupted conversation. Its smell: burnt tea, freshly lit fire, fish splayed open and hung out to dry on long sticks, those pungent antennae. Its noise: the cacophony of car horns, the flight of birds overhead, the blaring pop song wailing ever present in the background. Its light: the haze of morning giving way to the splintering bright of noon, and then 5:30 p.m. high tea, when the city looks like a giant, writhing picture show, chaos bathed in a patina of dusty gold.

The stories my grandmother told me are outlines, marks in black ink on a page, the salient details. Bombay was my birthplace. My mother had twelve children; six of them died. Everything Nana told me about her life was a remnant, a piece of a phrase. Whenever Nana told me stories, I badgered her for details, as many as I could think to ask. I worried that someday, when I needed to tell these stories to explain who I am, I would wonder about the color of the dress she wore in a certain black-and-white photo and she would no longer be alive to tell me. The sum total of what I could imagine about India was contained in my grandmothers brown vinyl album, hundreds of tiny prints with scalloped edges. What comes in between these details is my own invention; the shape and shade are the work of a grandchild to embroider. Ive spent years trying to paint the colors in.

A Fulbright Scholarship allowed me to quit my job, put my belongings in storage, and buy a one-way ticket to India. Now that Im here, the possibilities are dizzying. I look at the new stamp in my passport, trace the embossed letters with my fingertips, curious about what the next year will bring. In the upper left-hand corner of my visa is an R, for Research. So much of what I want to know about my grandmother and my ancestors is a mystery, a well-guarded secret. I am here as an amateur detective on that most American of journeys: a search for the roots of my own particular tree. This is a reverse migration. I have returned to the land that nurtured my grandmother and my mother, to walk where they walked, to make my own map within their maps. In my shoulder bag Im carrying a curious collection of objects: a crumbling mimeograph of family names, five yellowing books with beloved cracked spines, a handful of sepia photographs of unfamiliar faces.

I feel very far from Chestnut Hill, from the white clapboard house where I was raised, the tiny eyes of Mughal miniature paintings, the watchful, gilded gaze of my fathers great-great-grandmothers portrait. The presence of that house stays with me, the happy disorder of holidays unfolding in the embrace of its deep, wide doorways and dark wood. It was a solid kind of place, anchored by my three parents: my father, my mother, and my maternal grandmother, Nana. As a child I thought of our home as a miniature kingdom, ruled by a fierce and benevolent triumvirate. Its the prospect of adulthood that has brought me here, seeking Bombay, the backdrop of the stories I grew up with. I want to know if it exists, the mythic home my mother and my grandmother spun in their stories. I want this city to fill the gaps in my understanding and make me whole.

As my taxi speeds through Bombay traffic, a memory of Nanas voice, its quality of hushed electricity, rings in my ears:

Your grandfather built me a house in Bombay, facing the ocean. You could hear the sound of the waves as you slept, as if you were sleeping in a ship....

WHAT I KNOW ARE FRAGMENTS. I am here to weave them together, to create a new story, a story uniquely my own.

PART ONE

STORY TELLING

THE PAINTED CITY

CHESTNUT HILL, 1985 BOMBAY, SEPTEMBER 2001

In the upstairs front hallway of my childhood home near Boston there hung a large, vivid portrait of my mother. It was painted by Bombay cinema painters, those billboard romantics, homesick for undivided India. I remember when the painting first arrived, a sticky evening in 1985, my brother, Cassim, my father, my grandmother, and I impatiently waiting at Logan Airport among a throng of expatriates from the Subcontinenta sea of brown faces and my tall white father, forming a ring outside of International Arrivals, there to meet the night flight from Karachi. The double doors swung open with a mechanical snap and thud; the passengers began to pour through. Signs with handwritten names went up like a flock of birds, flap-flap, higher! Higher! And cries of Over here! Over here! And There she is!