Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

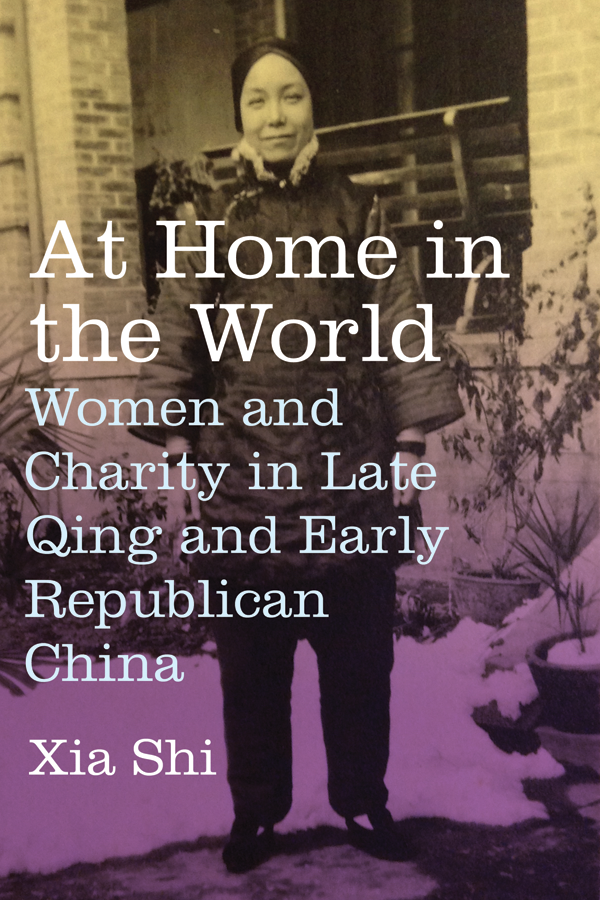

AT HOME IN THE WORLD

AT HOME IN THE WORLD

Women and Charity in Late Qing and Early Republican China

XIA SHI

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54623-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Shi, Xia, 1979 author.

Title: At home in the world : women and charity in late Qing and early Republican China / Xia Shi.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017034643 (print) | LCCN 2017045902 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231185608 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Women in charitable workChinaHistory | Women philanthropistsChinaHistory. | WomenChinaSocial conditions. | Sex roleChinaHistory. | CharitiesChinaHistory.

Classification: LCC HV541 (ebook) | LCC HV541 .S55 2018 (print) | DDC 361.7082/0951dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017034643

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover image: Tso Wu Lao Tai Taiour hostess. Madame Zuo (Tso) stands with bound feet in front of the Changsha YWCA building located at her home in Changsha. From Box 67, Maud Russell Papers, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library.

CONTENTS

I have accumulated many scholarly and personal debts for the completion of this book over the years, so please forgive me if I fail to enumerate them all here. First, I feel fortunate to have worked during my doctoral studies with Kenneth Pomeranz and Jeffrey Wasserstrom, who together taught me a combination of scholarly and life skills. I cannot express enough my gratitude to them, for their knowledge and advice enabled me to grow so much during these years. Anne Walthall not only taught me knowledge beyond China but also carefully read every word of the manuscript when it was still a draft and offered much-needed advice thereafter. Qitao Guos cheerful spirit and hospitality combined with his erudite Chinese knowledge made his classes relaxing and enjoyable for both me and my wonderful classmates.

I am grateful to the following organizations for providing funding to support my research at different stages. A postdoctoral fellowship from the Henry Luce Foundation/American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) Program in China Studies in 201516 enabled me to complete a major round of revisions of the book. New York Public Library (Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations) provided a short-term research fellowship in summer 2015 to conduct research there. China Cultural Time Foundation offered crucial funding to support my research in China in 201112. In addition, I was assisted by a Grierson and Bain Scholars Fellowship at the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College; a small grant from the China and Inner Asia Council of the Association of Asian Studies; and a travel grant from Stanford Universitys East Asia Library. I also appreciate the financial support I received from UC-Irvines Center of Asian Studies, Humanities Center, and International Center for Writing and Translation.

I am grateful for the help I received from the following archives and libraries and their staff members: the UC-Irvine library and its interlibrary loan services (special thanks to Ying Zhang, the East Asian librarian), the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College, the Manuscripts and Archives Division of the New York Public Library, Stanford Universitys East Asian Library, the National Library of China (particularly its gazetteer branch), Peking University Library, Qingdao Municipal Archive, Shanghai Municipal Archive, and Shanghai Library. I thank Li Guangwei, who not only shared with me copies of valuable sources about the Daoyuan but also accompanied me twice to interview Cong Zhaohuan, who generously recounted the history of the Cong familys engagement with the Daoyuan from the 1920s to 1940s. I also appreciate the help of David Igler and Marcus Konda. My appointment as a research associate at UCIs School of Humanities enabled me to access its library resources to further my research even after graduation.

Sincere thanks go to my colleagues at New College of Florida: David Rohrbacher read a draft of this book and offered many helpful suggestions; David Harvey and Carrie Bene gave me useful tips on the publication process; and Jing Zhang and Fang-yu Li shared my interest in China, Asian food, and stimulating conversations.

At Columbia University Press, I thank Anne Routon for taking an early interest in my book and Miriam Grossman for being there whenever I had questions. Additionally, I thank Bryna Goodman, Gail Hershatter, Johanna Ransmeier, and two anonymous reviewers for reading earlier drafts and making valuable suggestions.

My Chinese history cohort at UC-IrvineNicole Barnes, Maura Cunningham, Pierre Fuller, Nuan Gao, Christopher Heselton, Miri Kim, Jennifer Liu, Kate Merkel-Hess, Wensheng Wang, and Chen-Cheng Wangoffered friendship, helpful exchanges of expertise and advice, and engaging conversations in and after classes.

Finally, I am grateful to my parents and friends in China who were so generous to me over the years, even though I could not visit them often enough. DS helped edit many draft chapters over email and offered welcome suggestions. I feel fortunate to have had the company of my family along the journey over the years. To Jojo, Farley, Gumbo, and Sam: your presence brings me daily joy and reminds me of the fun world outside of academia.

Part of appeared in preliminary form in Stepping Into the Public World: Cases of Guixiu Philanthropic Activities in Late Qing China, Frontiers of History in China 9, no. 2 (June 2014): 24779. I thank Brill Press for granting me permission to include it in this book.

Y ale-educated James Yen is often celebrated as the chief organizer of the Mass Education Movement, which brought literacy and other benefits to millions of Chinese citizens in the 1930s. However, it is rarely known that he was selected and supported by a woman. For nearly a decade, a Chinese woman with bound feet, Zhu Qihui (best known as Madame Xiong Xiling), raised most of the money for the movement; she chose Yen to be its vice chairman. Yens prominence has blinded historians to the role of Zhu, who embodies a seeming impossibility, examples of which we will see throughout this study: a domestically oriented woman without modern education who was also an effective progressive activist in early twentieth-century China.

This book focuses on married, nonprofessional Chinese women without modern educations and investigates how they repositioned themselves through little-known charitable, philanthropic, and religious activities in a changing urban public world. It covers roughly the 1870s to the 1930s, spanning the late Qing dynasty (Chinas last dynasty, established by the Manchus) and the early Republican era (19121949), before the full-scale invasion by Japan. This crucial historical period witnessed a series of military defeats of the Qing dynasty by Western powers and its forced opening to the world. Subsequently, an increasing number of Chinese intellectuals, reformers, and revolutionaries came under the influence of the West and rejected the foundations of Confucianism. Both state and local elites carried out various modernizing reforms, which stimulated urban and commercial development and intellectual change. In the gender realm, womens domestic seclusion gradually lost its legitimacy as a marker of virtue and respectability, and more and more women began to actively engage with the public arena newly opened to them. In this context, this book, through concrete case studies, offers a glimpse into how some women successfully adapted themselves to be active and effective public actors in a rapidly changing society without repudiating roles that gave them continued access to important material and ideological resources. It does not intend to provide comprehensive coverage of womens charitable and philanthropic activities, but by investigating a hitherto unexamined aspect of womens livescharity and philanthropyit will not only make the public activities of these women visible but also highlight the significance of charitable and philanthropic activities as forms of political, social, civic, and religious engagement, socializing, and networking.