A Dictionary for the Modern Pianist

Dictionaries for the Modern Musician

Series Editor: Jo Nardolillo

Contributions to Dictionaries for the Modern Musician series offer both the novice and the advanced artist lists of key terms designed to fully cover the field of study and performance for major instruments and classes of instruments, as well as the workings of musicians in areas from composing to conducting. Focusing primarily on the knowledge required by the contemporary musical student and teacher, performer, and professional, each dictionary is a must-have for any musicians personal library!

All Things Strings: An Illustrated Dictionary by Jo Nardolillo, 2014

A Dictionary for the Modern Singer by Matthew Hoch, 2014

A Dictionary for the Modern Clarinetist by Jane Ellsworth, 2014

A Dictionary for the Modern Trumpet Player by Elisa Koehler, 2015

A Dictionary for the Modern Conductor by Emily Freeman Brown, 2015

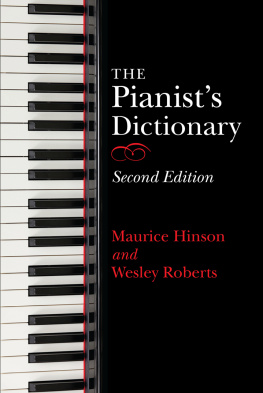

A Dictionary for the Modern Pianist by Stephen Siek, 2016

A Dictionary for the Modern Pianist

Stephen Siek

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2017 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Siek, Stephen, author.

Title: A dictionary for the modern pianist / Stephen Siek.

Description: Lanham, Maryland : Rowman & Littlefield, 2017. | Series: Dictionaries for the modern musician | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016023499 (print) | LCCN 2016024438 (ebook) | ISBN 9780810888791 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780810888807 (electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: PianoDictionaries. | PianistsBiographyDictionaries.

Classification: LCC ML102.P5 S6 2016 (print) | LCC ML102.P5 (ebook) | DDC 786.203dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016023499

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

For Donald Hageman

Pitch Range Chart

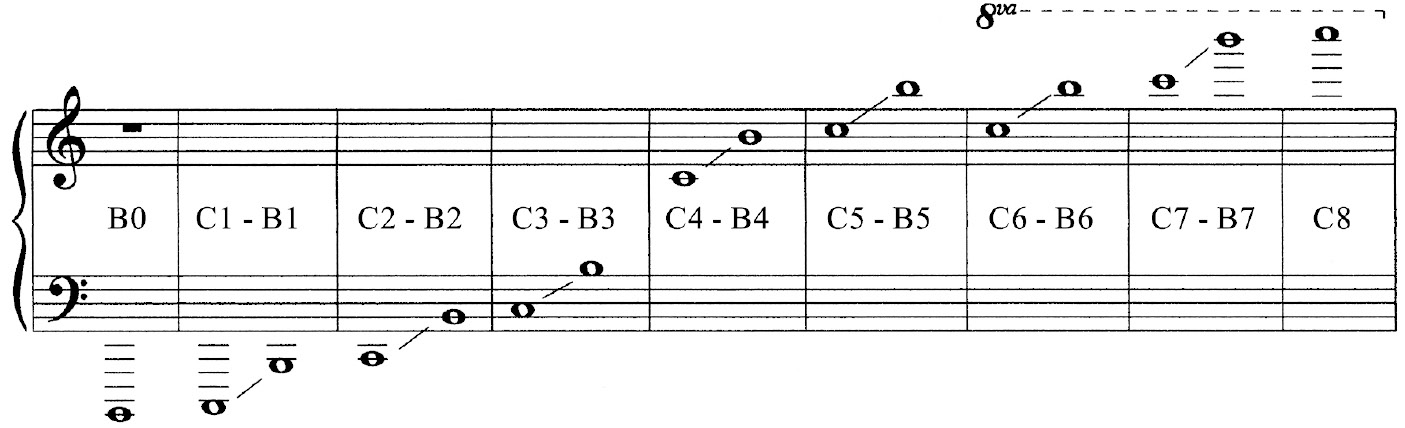

ASA (Acoustical Society of America) Method of Pitch Identification

All books in the Rowman & Littlefield Dictionaries for the Modern Musician series use the ASA (Acoustical Society of America) method for pitch identification, and this is the system used in this volume. As is customary with many keyboard charts, the numeral zero is used for those pitches below C1. However, what is sometimes termed the modified Helmholtz system (below) is generally preferred by piano makers, technicians, and many museums for indicating keyboard compass, and that chart has been included below for easy reference and comparison.

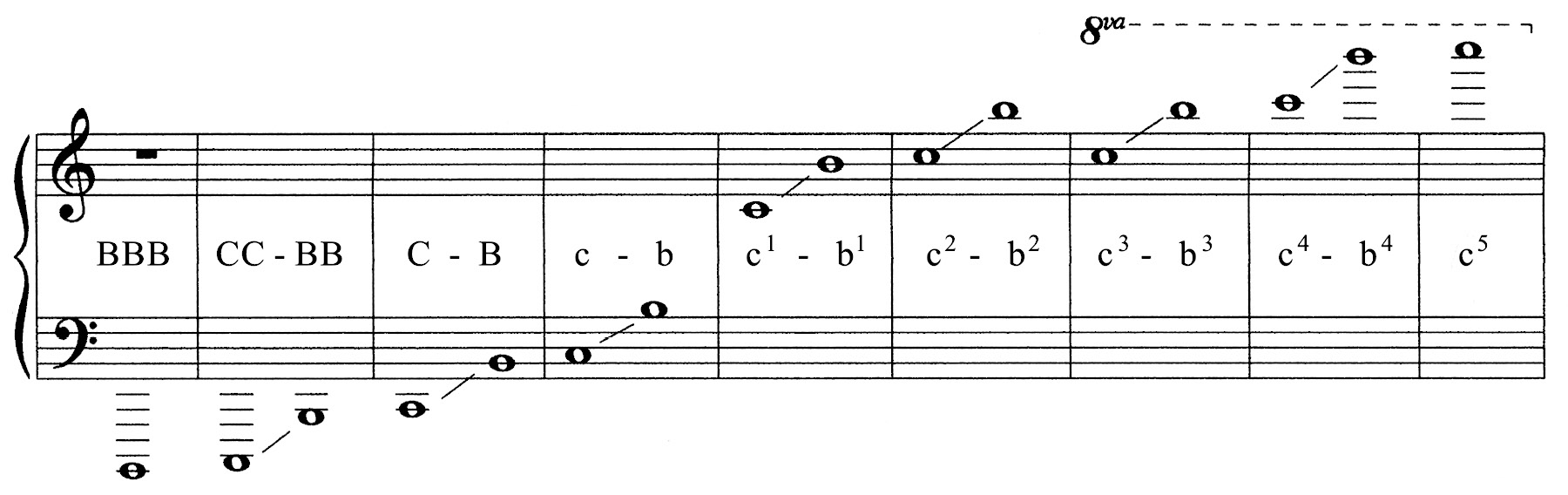

Modified Helmholtz Pitch Designation System

Modified Helmholtz Pitch Designation System used by the American Musical Instrument Society (AMIS), by museums in their instrument catalogs, by auction houses selling musical instruments, and often by musicians asking about the compass of a piano they are considering playing in concert.

Preface

Since nearly all dictionaries require selectivity, the modern pianists world presents a number of daunting challenges to anyone bold enough to chronicle its essentials between two covers. At least some of those challenges are well understood by experienced performers and teachers, for over the past quarter century the profession seems to have expanded in two opposing directions. First, the new technologies surrounding digital keyboards are accelerating to the point that even a dedicated technophile may have difficulty staying current with the most cutting-edge developments. At the same time, virtually any pianist who has studied or taught in a college or conservatory over the last several decades has observed the increased emphasis being placed not simply on performance practices of earlier periods, but on the actual instruments used before 1840instruments now being both restored and replicated by highly skilled craftsmen. At present, both of these movements have carved unassailable footholds in the modern pianists world, though both were considered little more than novelties a generation ago.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the partisans of period instruments and the devotees of electronic keyboards have not always found common ground, but the artists and teachers who focus on traditional instruments and repertoire have also observed some disturbing trends over the last few decades: for amid shrinking budgets and declining enrollments, their students often seem less concernedand less informedabout the rich legacy that has shaped their art. While some have suggested that we simply live in an age overly obsessed with the here and now, others have attributed the lack of awareness to proliferating competitions that tend to promote more homogenous playing, a style more often concerned with accuracy than artistry, and an approach that bears little resemblance to the individuality once associated with the so-called Golden Age of pianism. But whatever the causes, it seems paradoxical that talented students should spend years studying Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, or Debussy in an effort to aid their awareness of the composers intentions, while their exposure to the Bach of Edwin Fischer, the Beethoven of Artur Schnabel, the Chopin of Alfred Cortot, or the Debussy of Walter Giesekingperformances that were once considered iconic to generations of pianistshas likely been intermittent at best. To compound the irony, todays students have unprecedented access to the most treasured performances of the past, whether via the Internet or through the large number of commercial reissues available on CD, an ease of access that their teachers could scarcely have imagined in their own student days.

Since, for a variety of reasons, the pianists world has always been driven more by personality than terminology, the majority of entries in this volume focus on the major pianists and teachers of the past two centuries. Perhaps in some measure, this approach may help enrich the modern pianists world, since music schools rarely seem to address the legacy of artistic piano performance in a systematic fashion. Thus, with the understanding that the printed word can never take the place of a recording or a live performance, this book has been designed to offer detailed background, as well as easy reference, to those both familiar and unfamiliar with the seemingly endless array of notable performers who have shaped our pianistic heritage. Admittedly, such an alphabetical survey amounts to little more than a selective overview, and the necessity of keeping this work from expanding to multiple volumes has also required many omissions. The most painful exclusions have resulted in the absencewith a few delimited exceptionsof countless younger, often magnificently gifted artists who have not yet reached the half-century mark. Although this decision was dictated primarily by spatial considerations, it could be argued that it was not entirely arbitrary, since by the time pianists reach mid-life, it often becomes easier to evaluate the mark they are likely to leave on their profession. And it may offer some consolation to note that the majority of younger pianists today, especially those under management, rarely want for publicity. In fact, they are likely to have websites detailing their backgrounds and even offering sound samples, a status never enjoyed by the majority of great artists who are no longer with us.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.