Contents

Guide

Page List

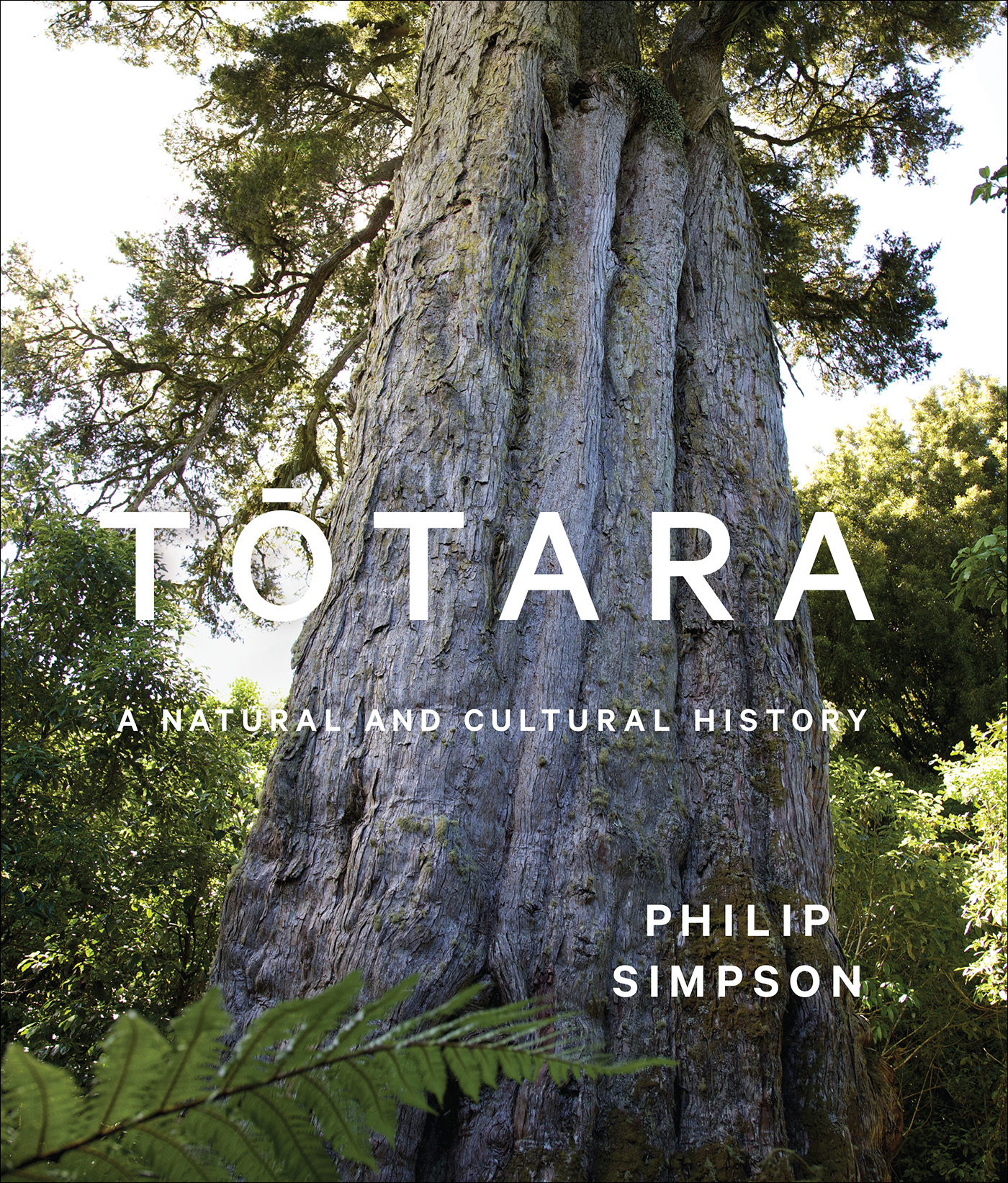

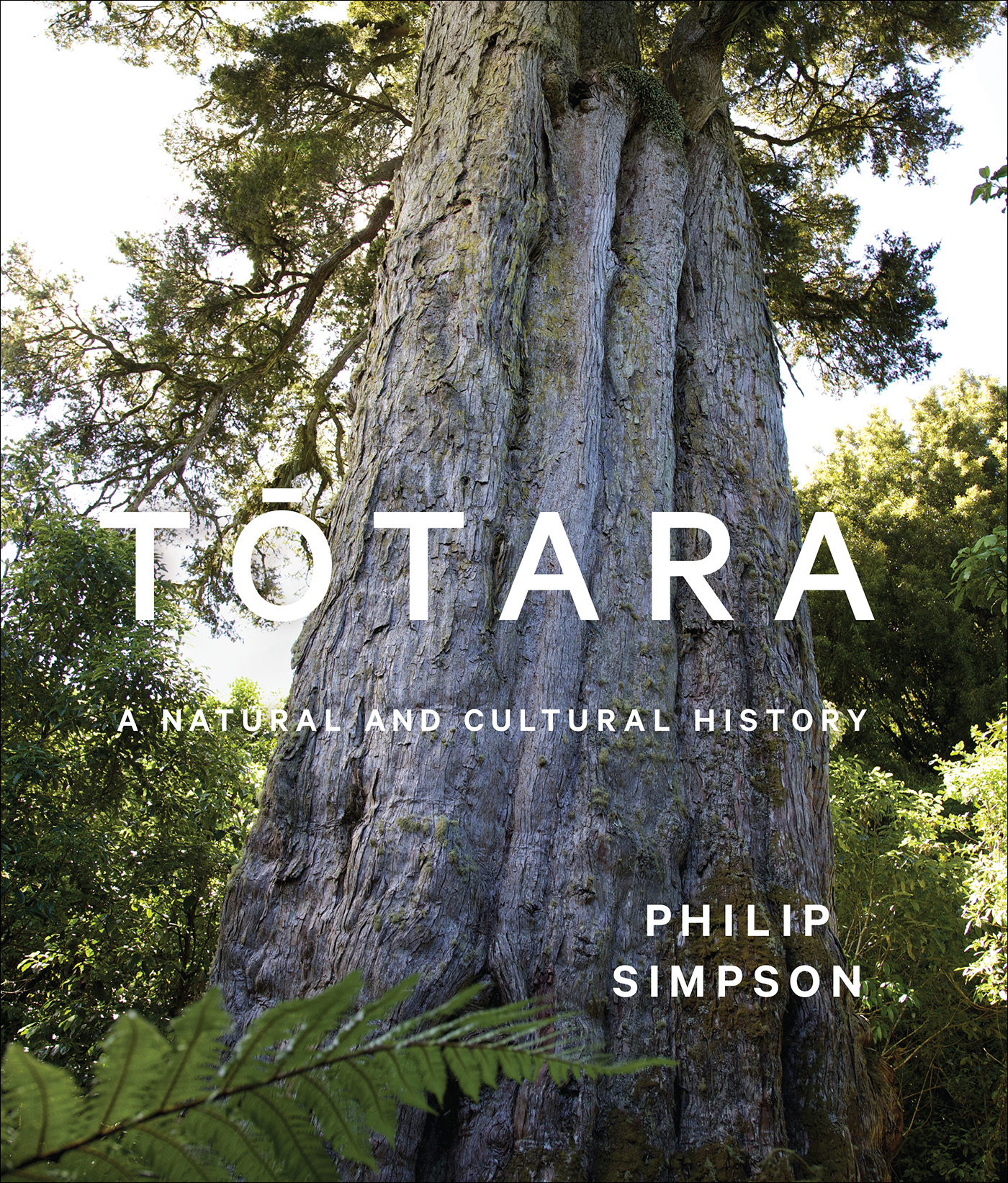

Philip Simpson is a botanist and author of Dancing Leaves: The Story of New Zealands Cabbage Tree, T Kuka (Canterbury University Press, 2000) and Phutukawa and Rt: New Zealands Iron-hearted Trees (Te Papa Press, 2005). Both books won Montana Book Awards in the Environment category and Phutukawa and Rt also won the Montana Medal for best non-fiction book. Simpson was awarded the Creative New Zealand Michael King Writers Fellowship to work on Ttara: A Natural and Cultural History.

Frontispiece: The ttara excited our astonishment, from the bulk and height to which it grew (John Nicholas, 1817).

TTARA

A NATURAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY

PHILIP SIMPSON

For two lost colleagues

Geoff Park, who brought conservation and botanical science together Ken Piddington, who ensured that Mori had a voice in conservation

Contents

Foreword

The skin of the ttara, the first tree that Tne created, evokes chiefly qualities such as strength, protection and persistence.

O NE OF MY SPECIAL CHILDHOOD FRIENDS AT Takaka District High School in Mohua (Golden Bay) was Peter Simpson, a bus boy from Uruwhenua up the valley. Some weekends Peter would stay in town with us, and occasionally Id stay at his place, nestled in that marvellous landscape at the head of Takaka Valley, richly deserving its special name. Ttara trees were everywhere in those days, and they still are maybe a little thinner on the farm flats, but regenerating in droves on the hills now that the fires have gone out. Peters wonderful parents, helped by their big family, ran a farm and tree nursery one of the few in the bay. Trees, shrubs and plants, particularly natives, were their life; and much of Ironstone Creek, carving its way into the Takaka Hill marbles opposite their farm, was virgin forest or regenerating bush, largely thanks to the Simpsons kaitiakitanga.

I treasure those memories. I tried, unsuccessfully, to emulate Peter and Philip practising their reckless Charles Blondin stunts, walking along the tops of ttara fence posts; I still have a scarred leg to prove I was no good. Heading home from swimming in the Takaka River bounding the farm, wed sprawl beneath ttara and wild fuchsia and pluck the sweet, resinous drupes. Sheep mustered into pens fenced by ancient ttara pickets, the flattened slabs lichen-encrusted, the whole held together by deftly twined No. 8. Home-made farm trailers and carts planked with hand-adzed ttara boards. Torchlight explorations of hidden glow-worm grottos along banks overshadowed by gigantic ttara; a scary, magical world. Solemn evenings, wide-eyed at adults stories about giant ttara up the Ironstone and denizens lurking in Harwoods Hole further up. Accounts of dodgy brazen neighbours driving horses across the river to steal ttara logs from the family. My garbled version of an aunts terrifying myth of the resident taniwha, a fierce sentinel posted not far away at the head of the Valley whose job uruuruwhenua was/is to protect our Mohua land and its inhabitants. And the sadness, the tears in everyones eyes, at discovering a beloved ancient ttara blown down overnight as moving as any wake. Kua hinga te ttaranui, tangi tonu, tangi tonu!

Of course I also knew Philip at school, but he was in my sisters class younger than Peter and me, and, like all younger brothers, to be ignored. On my very first visit to the Simpsons I was forced to abandon these puerile prejudices. I have very clear recollections of this earnest seven- or eight-year-old boy poring for hours over beautiful scrapbooks he had put together. Dozens of pages of pressed and dried leaves, flowers, fruits and twigs of native trees and shrubs, accompanied by his own sketches, and magazine clippings of mature specimens. All catalogued with common names, botanical names, where hed collected them, dates when collected, and minute details by which he could identify each. Specimens at all stages of preservation were carefully stacked around his room awaiting his attention. I was amazed... and ashamed at my own pathetic collection of pretty postage stamps. Here was child genius; here was real research, enterprise and systematic endeavour; here was Simpson upbringing coming to the fore. Even our gorging on wild fruits had a serious side: Philip always collected any seeds from our gluttony, took them home, dried and labelled them for the nursery.

Peter, Philip and I are alumni of the same schools and university, but after graduation I lost track of Philips fortunes until a few years ago when I discovered Dancing Leaves, the first in this magnificent series. While I marvelled at its informative, flowing narratives and the exquisite beauty of its layout, the book came as no great surprise to me. This was the work of the boy from Uruwhenua, come to fruition. Then came the beautiful Phutukawa & Rt. Philips love of natural places, his years of botanical study at home, Takaka District High, Nelson College, Canterbury University and then overseas his wealth of experience in the public service as a botanist, his time as a consultant advising farmers on the natural values of their land, and his self-confessed love of gardening, drawn from his family heritage of nursery work, flourish again now in Ttara.

As a part-Mori raised staunchly but in the largely Pkeh worlds of Golden Bay and Nelson, I know how difficult it can be to have a foot in both camps. Philip, through his experience in writing about t kouka, rt and phutukawa, all treasures in Te Ao Mori, has again comprehensively explored the legendary origins, practical values, artistry and conservation politics keenly held by iwi since time immemorial. It is a tribute to Philips personality, as much as his academic skills, that again he has been accepted by so many kaumtua and kuia who willingly shared their stories and allowed him to photograph their sacred marae, a privilege denied to most. My wife Hilary and I have written about the history of Mori in Te Tau Ihu (NelsonMarlborough). We know how difficult it is to assemble complex, and sometimes conflicting, information and to interpret it robustly. To have all the threads of the mighty ttara drawn together in one place has unparalleled educational value for our leaders and children alike.

A few months ago Philip asked me whence came the place name Totaranui in western Tasman Bay. I wasnt certain, but I recalled a pre-dawn trip in about 195152 with my dad and his hunting mate, up the ridge above the Awaroa turnoff on the Totaranui Road. I was ten or eleven. Back then a crude arrow saying Big Totara nailed to a roadside tree indicated a rough track, and I had a vague recollection of trudging in the gloom up to a very large ttara where we paused to catch our breath. Philip recently found where the sign had been nailed, the old track, and the tree itself, alas now dead from possum browse. Nevertheless, he confirmed the possible origin of the name... and also the accuracy of my memory... always a relief at my age!

Philip has written a history of Aotearoa/New Zealand from the ttara perspective. He has seen it as part of the primeval natural world, he has clearly portrayed why ttara is the leading rkau rangatira chiefly conifer to Mori, and he has shown how critical ttara was to successful European settlement. It is small wonder that Philip regards the protests to ensure ttara conservation at Pureora and Whirinaki as pivotal events in New Zealand history, events that have shaped our cultures as clean and green, rightly or wrongly. Philips work will never be outdated or repeated. It stands to educate and inform us about this tree in our ecology, our history and our cultures.