Hello Girls & Boys!

Hello Girls & Boys!

A NEW ZEALAND TOY STROY

DAVID VEART

Introduction

Out of the Toy Box 1

Toys from the Waka

Out of the Toy Box 2

New Arrivals, 18401900

Out of the Toy Box 3

Toys in Depression & War, 19001945

Out of the Toy Box 4

A Golden Age? 19461960

Out of the Toy Box 5

Toys to the World, 1960s1970s

Out of the Toy Box 6

The Elves & the Rogernomes, 1980s

Out of the Toy Box 7

End Games, 1990s2000s

Conclusion

Toys in the Joined-up World

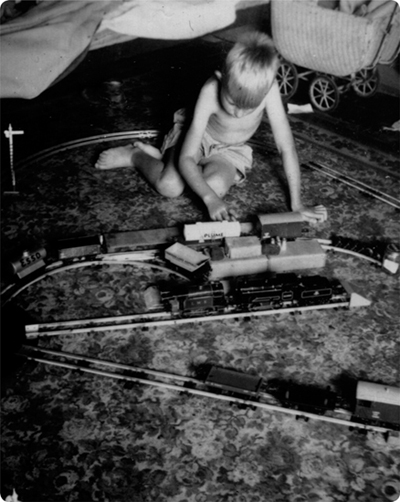

The author as a young train enthusiast. As a child growing up in the 1950s I had the advantage of having an Australian grandfather who arrived every Christmas with a bag of toys, many of which were unobtainable in New Zealand. These included trains and over five or six Christmases my railway grew. I note now that the items he brought included both British Hornby and Australian Robilt material.

Introduction

It could be the State picture theatre, Onehunga, in 1960. The familiar music and the antipodean-BBC accent of the narration take me straight back to the Saturday matinees of my childhood. It is in fact the viewing room at Archives New Zealand in Wellington, 52 years later, and I am watching a National Film Unit feature, Pictorial Parade, produced in pre-television New Zealand so people could share images of the countrys post-war progress. With a quarter of the nations population under nine years of age the toy industry is booming, intones the voice, followed by high-speed dum-dum-dum-dum-dum music indicating that we are in a modern factory and that this is the machine age. Close-up shots show workers, both Mori and Pkeh, assembling toys.

A womans hand, armed with what look alarmingly like forceps, reaches into a metal tube and pulls out a dolls head, which she stacks in a pile next to her machine, an ossuary of pink plastic skulls. The voice again: Eternal toys to take a child a million miles away but still keep him under the watchful eye of Mum. Men assemble toy Jeeps and women pack train sets; disembodied hands air-brush doll faces to plastic perfection.

This government propaganda from another age was filmed in the South Auckland toy factory of Tri-ang, a company whose presence in New Zealand was the product of high-level negotiations with English toy giant Lines Bros Ltd by Walter Nash, minister of finance in the first Labour government, which not only looked after us from the cradle to the grave but also helped to supply toys to amuse us along the way.

The toys shown in this film are part of our culture and they tell our story, often in ways that more serious things cannot. At play, people let their guard down and allow cultural insights that may otherwise be obscured. As an archaeologist I have spent much of my adult life studying the history of human behaviour by examining the things we leave behind: potsherds, food refuse and stains in the soil showing where houses and buildings once stood. So why not toys? They, too, are artefacts. Most children do not leave written records; toys tell their story. For New Zealanders, this is a story of a country settled by Polynesian explorers followed by waves of Europeans, people of the Pacific and migrants from Asia. The tamariki climbing off the first waka brought things we recognise as toys although, in the Mori world, adults and occasionally demi-gods played with toys as well. They were joined in the nineteenth century by other children, bringing their own playthings, and a few that both groups shared: toys like knucklebones, tops and kites.

For many children, Sunday was a day without toys, a day to be spent in contemplation, not having fun. As with most rules there was an out-clause: if the toy was in some way religious then play could continue and toys like this Noahs ark became popular.

Initially, these children were seen as wild, running out of control in a wild new land. The newspapers were filled with accounts of the shanghai menace and thousands of birds, windows and glass insulators on power poles fell victim to apparently feral and armed children. And they were not just boys. Until adolescence, when domestic tasks and adult clothing changed their world, many girls played in the same way as boys. When there were only fifteen children in the district and you needed a rugby team, some of the players just tucked up their skirts and ran onto the field. And then there are all the smashed dolls found in nineteenth-century rubbish pits: the result of wildness or simply careless play?

In the nineteenth century, toys were sometimes simply miniatures of the real thing, made by the same manufacturers. Toys like this miniature pot and kettle were probably produced by the local tinsmith.

Gradually, children were tamed, although the commentators description of children playing under Mums watchful eye may have been a little optimistic. I was ten years old when that film was made and can still remember a few wild episodes with the watchful eye at least a mile away.

Toys help to define the place of children in New Zealand. In Mori society the association of toys with childhood was not sharply differentiated, but the distinction was more certain in later periods and the Customs Department in 1956 assessed toys as things designed principally for the entertainment of children. To adults, toys seemed ephemeral. When hard times arrived toy imports were restricted; toys were banned in wartime and toy manufacture was cut back in later periods of economic stress. In the 1960s one toy retailer commented that the monthly bill for imported Scotch whisky was the equivalent of a whole year of toy imports but then children do not vote. Toy safety was a factor too: government was slow to regulate toys that used fire, had sharp edges or were covered in toxic paint. And it was not just a matter of possible physical damage; the psychological effects of war toys and associated violent television programming in the 1980s concerned many parents. Opposition grew and petitions were collected, with minimal governmental response.

Mori children celebrating an English festival with explosive toys bought from a Chinese shopkeeper who celebrated his own cultural festival, Chinese New Year, at a time when firework sales were usually banned.

In this Northwood Brothers photograph, taken somewhere in Northland, a group of children, Mori and Pkeh, admire a fine model yacht.

Next page