CONTENTS

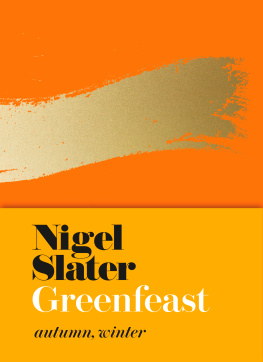

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2019

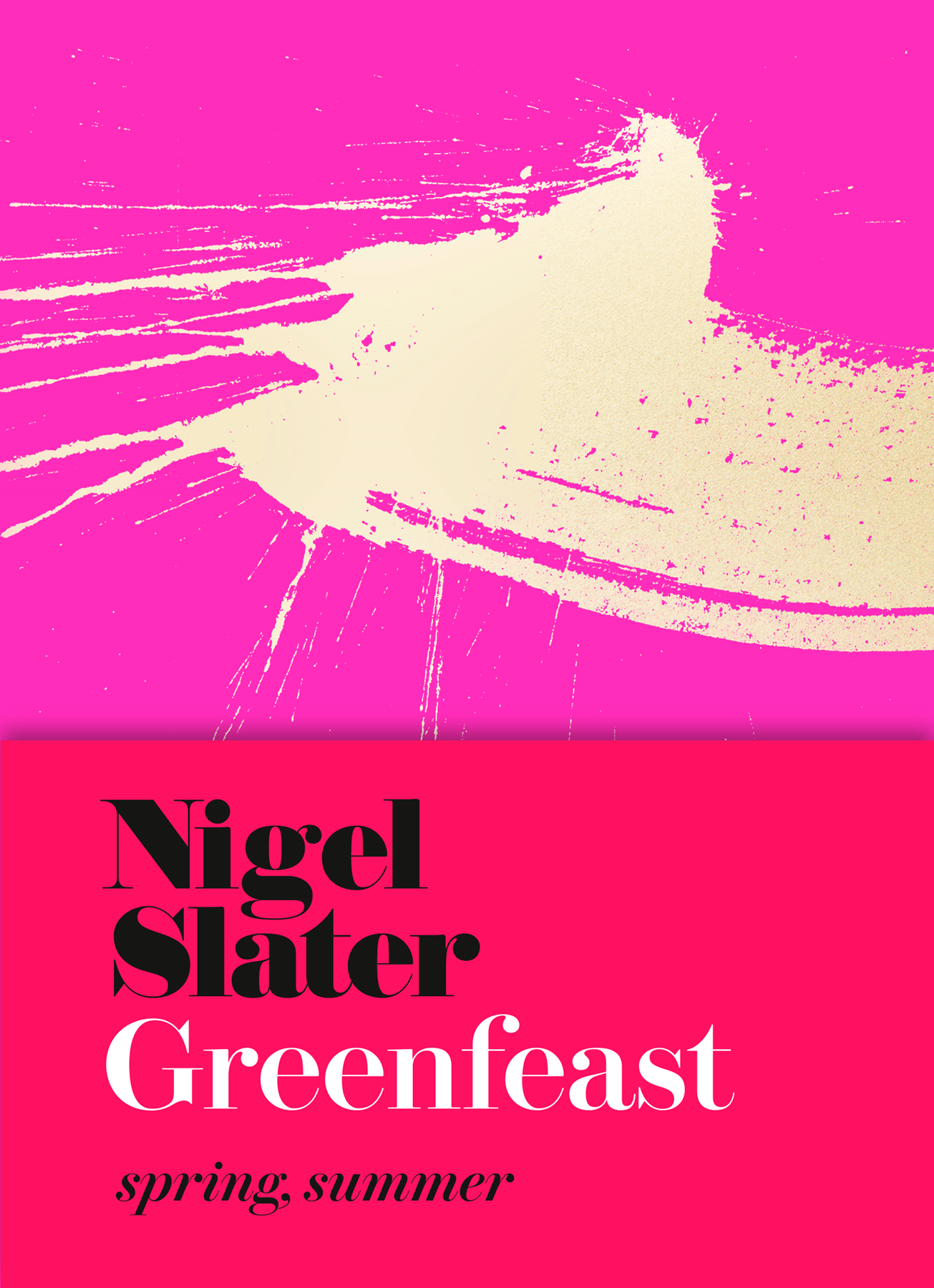

Text copyright Nigel Slater 2019

All recipe photographs Jonathan Lovekin 2019

Except p. 295 Nigel Slater 2019

Brushstrokes copyright Tom Kemp 2019

Nigel Slater asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Design by David Pearson

Author photograph by Jenny Zarins

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008333355

Ebook Edition March 2019 ISBN: 9780008336622

Version: 2019-03-21

For James

Tom Kemp

Tom Kemp trained as a calligrapher, absorbing the large number of Western scripts written with a quill pen. It was an introduction to the square-edged brush, however, which led to his current work. He studied the heavily-doubted theory that the best classical Roman inscriptions were first written with the brush directly and swiftly on marble; the subsequent carving was just a way of fixing this handwriting in place. Tom rediscovered many of the techniques needed to prove the theory, summarising his findings in a book, Formal Brush Writing , published in 1999. Since then he has taught this Roman calligraphic technique in classes around the world. At the same time, he started to explore the idea of writing itself and began to abstract away from letters and words, resulting in what he calls writing without language. Seven years ago, he began to learn the craft of pottery which he now uses to make complex, curved porcelain surfaces on which he writes.

tomkemp.com

Instagram @tom_kemp_

Contents

There is a little black book on the kitchen table. Neatly annotated in places, virtually illegible in others, it is the latest in a long line of tissue-thin pages containing the hand-written details of everything I eat. This is not one of the kitchen chronicles where I write down recipe workings and shopping lists, ideas and wish lists, but a daily diary of everything that ends up on my plate. If I have yoghurt, blackcurrant compote and pumpkin seeds at breakfast it will be in that little book. Likewise, a lunch of green lentils and grilled red peppers or a dinner of roast cauliflower and a bowl of miso soup. Each bowl of soup, plate of pasta and every mushroom on toast is faithfully logged. I dont know exactly why or when I started noting down my dinner, but these little books are now filled in out of habit as much as anything else. The notes are often made at night, just before I lock up and go to bed. I suspect my little black books will be buried with me.

I occasionally look back at what I have written, often as I change one journal for the next. One of the points that interests me, and perhaps this is the main reason I have kept the daily ritual going for so long, is that I can follow how my eating has changed, albeit gradually, over the years. There are of course unshakable edibles, (I seem to have started and ended each days eating with a bowl of yoghurt for as long as I can remember), but I also find marked changes in what I cook and eat. The most notable is the quantity, I definitely eat less than I used to, and there is a conspicuous move towards lighter dishes, particularly in spring and summer.

But heres another thing. Despite being resolutely omnivorous, it is clear how much of my everyday eating has become plant-based. Although not strictly vegetarian (the bottom line for me will always be that my dinner is delicious, not something that must adhere to a set of strict dietary rules), much of my weekday eating contains neither meat nor fish. I am not sure this was a particularly considered choice. It is simply the way my eating has grown to be over the last few years. I do know, however, that I am not alone in this.

Greenfeast , like Eat before it, is a collection of what I eat when I finish work every day: the casual yet spirited meals with which I sustain myself and whoever else is around. The recipes are, like those in previous collections, more for inspiration than rules to be adhered to, slavishly, word for word. But unlike Eat , this collection offers no meat or fish. The idea of collecting these recipes together is for those like-minded eaters who find themselves wanting inspiration for a supper that owes more to plants than animals.

HOW I EAT

I rarely hand someone a plate full of food. More hospitable and more fun, I think, is a table that has a selection of bowls and dishes of food to which people can help themselves. And by that, I mean dinner for two or three as much as those for a group of family or friends. That way, the table comes to life, food is offered or passed round, a dish is shared, the meal is instantly more joyful.

In summer there will be a couple of light, easily-prepared principal dishes. Alongside those will be some sort of accompaniment. There may be wedges of toasted sourdough, glossy with olive oil and flakes of sea salt. Noodles that I have cooked, often by simply pouring boiling water over them, then tossed in a little toasted sesame oil and coriander leaves, or an all-singing and -dancing Korean chilli paste.

A dish of red pepper soup might sit alongside a plate of fried aubergines and feta. Crisp pea croquettes may well be placed on the table with tomato and French bean salad. Southeast-Asian noodles might be eaten with roast spring vegetables and peanut sauce and a mild dish of creamed and grilled cauliflower could turn up with a spiced tomato couscous. Two dishes, often three, are very much the usual at home. I find the thought of being able to dip into several dishes uplifting in comparison to a single plate piled high.

Much of what I cook in the spring and summer is exceptionally light, by which I mean it is unlikely to be carb-heavy or based on dairy produce. There are a few things that come out on a regular basis. Bowls of yoghurt that have been folded through with chopped mint and coriander, a splash of rice vinegar and chives. There are often some lightly pickled vegetables: usually carrots, beetroot or red onions. A tangle of sauerkraut turned with an equal volume of chopped herbs, or a tomato and basil salad. Like migratory birds, these are regular visitors to my summer table. There will be others too. Perhaps some rice with crisped onions and coriander or noodles tossed with crushed tomatoes, sea salt and red wine vinegar. There may be a dish of couscous with mint, golden sultanas and green peas, or new potatoes with olive oil, tarragon and lemon zest.

It is no secret that I have a deep affection for the cold months, but my love of summer cooking, its ease and laidback feeling is not far behind. There are highlights that turn up on the table from May to September and often beyond. A few pieces of melon rolled in the juice of a passion fruit for breakfast. A deep cup of miso soup with shreds of spring greens and lemon for lunch. The uppermost points of early summer asparagus tossed with ground sesame seeds and a trickle of toasted oil to accompany a salad of sprouted seeds and green peas. A single misshapen ball of burrata with an emerald ribbon of basil oil, or a cucumber, crushed and scattered with cool ricotta and mint leaves aside a bowl of avocado and green wheat. The list is almost endless.