Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2009 by Theresa Mitchell Barbo

All rights reserved

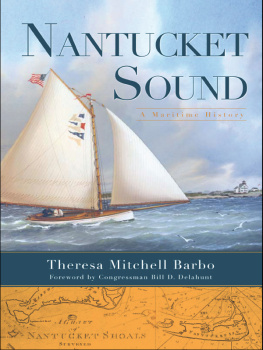

Front and back cover paintings by William R. Davis, courtesy of Susan and DeWitt

Davenport, Bass River. The map of Nantucket Sound that appears on the front cover is

courtesy of the Normal B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Libray.

First published 2009; Second printing 2010

e-book edition 2012

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.61423.306.0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barbo, Theresa M.

Nantucket Sound : a maritime history / Theresa Mitchell Barbo.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-59629-687-9 (alk. paper)

1. Nantucket Sound Region (Mass.)--History, Local. 2. Nantucket Sound Region (Mass.)--Description and travel. 3. Coasts--Massachusetts--Nantucket Sound. 4. Cape Cod (Mass.)--History, Local. 5. Marthas Vineyard (Mass.)--History, Local. 6. Nantucket Island (Mass.)--History, Local. I. Title.

F72.N34.B37 2009

974.49--dc22

2009026278

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To my son, Thomas

My basic principle is that you dont make decisions because they are easy; you dont

make them because they are cheap; you dont make them because theyre popular; you

make them because theyre right.

Theodore Hesburgh, University of Notre Dame

Do not go where the path may lead, go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

And to the memory of my maternal grandmother,

Josephine Linarello Ferraro,

who perished aboard the Italian liner Andrea Doria

south of Nantucket Sound

July 25, 1956.

And with much love for Josephines two daughters,

my mother, Clara Ferraro Mitchell,

and my dear aunt, Theresa Ferraro Caruso.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Nantucket Sound is many things to many people. For the visiting tourists, its the body of water they travel over on the way to Nantucket or the Vineyard. For fishermen, its where they work. It has been a source of local food and income for generations of draggermen, charter boats and weir fishermen. The arrival of species like the striped bass and squid will instantly draw hundreds to the Sound.

For those who live on the Cape and Islands, Nantucket Sound is a refuge with wilderness-like views over a landscape unmarred by man. It boasts splendid views, and during the summer its where local residents escape from tourists.

As land on the Cape and Islands became developed, the shore and waters of Nantucket Sound have been the focus of intense conservation debates for more than forty years. The most notable of these took place in the 1960s, when the Cape Cod National Seashore was established. Back then, there were some who felt that much of the Cape and surrounding waters ought to be added to the park system before it was too late. But any plans to include anything but the Lower Cape were considered politically suicidal. Any ideas of extending the protective umbrella of the federal government were abandoned, at least for the moment.

The next burst of conservation interest came during the 1970s, when energy companies were looking for places to drill for oil. Even though the Sound was of little interest, the widespread fear of a handful of drilling rigs blighting the landscape and threatening the fragile waters prompted state and local officials to create the Cape and Islands Ocean Sanctuary, designating all of Nantucket Sound a protected area. The sanctuary statute noted that Nantucket Sounds rich environment and scenic values were considered worthy of long-term protection and conservation.

Soon after the state created the ocean sanctuary, Congressman Gerry Studds and Senator Edward M. Kennedy filed legislationendorsed by the entire delegationto create an Islands Trust. That plan was envisioned as needed to protect the land and waters of the Vineyard and Nantucket and to require the federal government to promote the long-term conservation of the area. While the goals of the legislative proposal had significant support, the specific details of the plan faced mixed reviews. However, the debate alone inspired a number of local conservation efforts, including the creation of regional land use regulatory agencies and land banks to acquire conservation land on both Nantucket and Marthas Vineyard.

In the 1980s, as the federal government started designating a network of national marine sanctuaries, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts made Nantucket Sound its priority. The Nantucket Sound National Marine Sanctuary application filed by the governor and his administration stated:

Nantucket Sound contains distinctive ecological, recreational, historic and aesthetic resources that form the basis of the predominant economic pursuits of the area: fishing and tourism. Nantucket Sound is an important habitat containing spawning, nursery and feeding grounds and migration routes for a number of the nations important living animal resources, an area with high biological productivity and diversity of species, and a premier marine-oriented recreational and historic area of regional and national significance.

Back then there was no dispute over how the waters of the Sound were to be managed and protected. The debate was usually over who would do it. The state insisted that Nantucket Sound deserved the highest levels of protection, like the Cape Cod National Seashore. The states management plan included a ban on all forms of power generation, sand and gravel mining and the discharge of any marine wastes. However, the state proposed a unique system of management that would bring together state, local and federal systems into one overall and coordinated effort. Even though it would be a national sanctuary, the state would take the lead in the effort.

The Massachusetts plan was quite similar to the marine sanctuary established in the Florida Keys, where state and federal natural resources management staff and officials work under one overall management plan and one overall umbrella organization. The Florida plan also established a fund to provide federal dollars to pay for sewer projects and other measures to protect the coastal waters of the Florida Keys. The Massachusetts and Florida plans were ecosystem based, visionary and well ahead of their time.

The Nantucket Sound Sanctuary proposal was endorsed by an independent panel of scientists, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. The campaign to make Nantucket Sound a National Marine Sanctuary was precipitated, in part, by the anticipated outcome of a Supreme Court case, U.S. v. Maine, which involved coastal boundary disputes involving several states.

State officials, however, were worried about losing control of the middle portion of Nantucket Soundcalled the donut holewhich was fully protected under the states own ocean sanctuary statutes. The fear at the time was that a donut hole in the middle of Nantucket Sound would be exposed to weak federal controls. By the time the Supreme Court ruled in 1986 in favor of federal control over the middle of the Sound, the political climate on designating a new sanctuary to protect the area changed significantly. By then, Stellwagen Bank had also emerged as a candidate site worthy of national protection.

Next page