Growing much of what we eat has been one of the greatest joys of living at Hortulus Farm, and my passion for searching out unusual and interesting varieties of our common food plants remains unabated; so it is with great pleasure that I offer up to you eighty-five of the most winning edible plants on the planet.

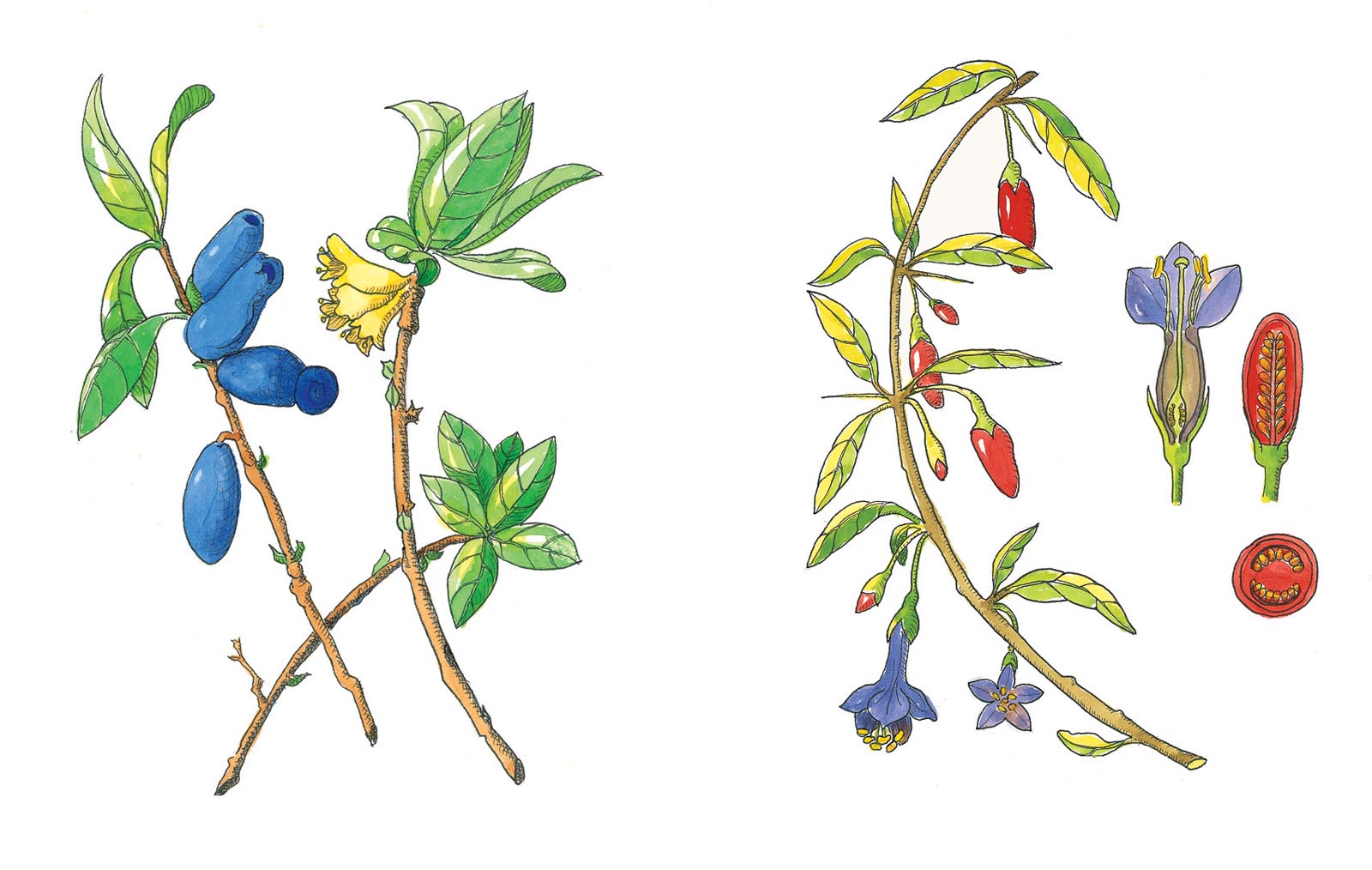

The world truly is our horticultural oyster, with exciting new cultivars and even entirely unfamiliar species, like the goji and the honeyberry, coming to us from every corner of the globe. As well, in this tome, I urge you towards the cultivation of some of our lesser known edible plants, like anise, chervil, the persimmon, and the lingonberry, any of which will not only provide you with new culinary avenues to explore but plenty of visual delight in your garden. And then there are the fascinating histories, antique employments, myths and lore, however occasionally misguided, surrounding even our most familiar fruits, herbs, and vegetables.

Have I personally grown every plant, shrub, and tree in this book? No, and for fairly obvious cultural and climatic reasons, most particularly some of the finicky fruit trees that require a daunting regime of spraying, pruning, and fruit-thinning. That said, I have been vigilant in both research and visitation of neighboring farmers and orchardists, and the varietal information and cultural advice I impart to you here you may rely on.

My sincere hope is that you will find these plant portraits as enjoyable to browse as they are informative and that you will be inspired to culture some of these wonderful edible plants in your own garden. And if youre ever in our neighborhood, please do come see what were growing on the farm!

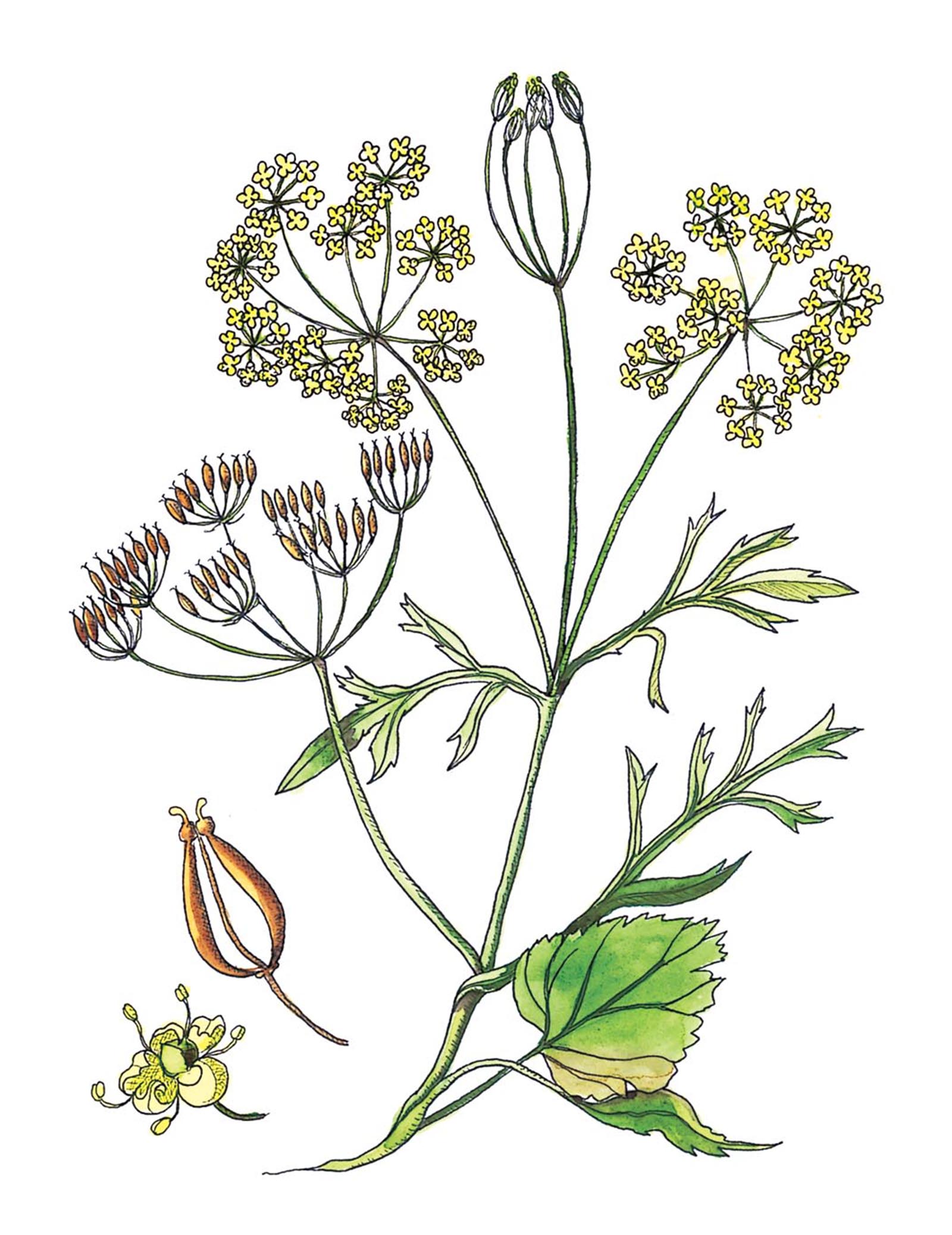

Anise

Pimpinella anisum

For the dropsie, fill an old cock with Polipody and Aniseeds

and seethe him well, and drink the broth.

William Langham, The Garden of Health, 1633

A nise, also known as anise seed, pimpinel, and sweet cumin, is a member of the parsley family and, like many umbellifers , is thought to be anciently native to Egypt, Greece, and parts of the southern Mediterranean. According to excavated texts, anise has been cultivated in Egypt since at least 2000 B.C., the flavorful seeds having been employed as a diuretic, a digestive aid, and to relieve toothache. Anise is mentioned in the seventeenth-century-B.C. works of Hammurabi, the sixth king of Babylon and author of the Code of Hammurabi, one of the first legal treatises in recorded history, and it is also known that Charlemagne adored this fragrant herb and planted it extensively in his gardens at Aquisgrana between A.D. 800 and 814. Anise was known to British herbalists by the fourteenth century A.D. and, according to Mrs. Grieve, was being cultivated in Great Britain by the mid-sixteenth century, when it was also introduced into South America by the Spanish conquistadors. The Pimpinella in anises botanical name derives from the Latin dipinella, or twice pinnate, in reference to its leaf form, and because of its pungent, licorice sweetness, anise saw broad medicinal application across all cultures it touched, but particularly for respiratory and digestive ailments.

Hippocrates, father of modern medicine, recommended anise for respiratory issues in the fourth century B.C., and the Greek botanist Dioscorides wrote in the first century A.D. that anise warms, dries, and dissolves everything from an aching stomach and a sluggish digestion to excessive winde and a stinking breath. John Gerard recommended it in his Herball of 1636 for the yeoxing or hicket [hiccup] as well as strengthening the coitus, and in 1763 Christopher Sauer maintained that it removes chill from the chest and staves off coughing fits. The breath-sweetening employment was also lauded by the British apothecary William Turner, who reported in 1551 that anyse maketh the breth sweter and swageth payne.

Interestingly, unlike many early herbal claims, most of those attached to anise are surprisingly smack on the money. We know now that anise seeds contain healthy doses of vitamin B, calcium, iron, magnesium, and potassium, as well as athenols, which aid in digestion, calm intestinal spasms, and reduce gas. A tisane made of anise has also proven effective in calming both coughs and chronic asthma, and, of course, anise is the main flavoring ingredient in those potent nectars anisette, pastis, and absinthe, the latter of which will pretty much calm anything into submission.

Anise is also a very pretty plant, with bright green coriander-like foliage and lovely, diminutive white-and-yellow flowers held in feathery umbels, the whole of it growing to about 18 inches.

Anise

Anise seeds are actually the fruit of the anise plant; when dried, they are transformed into those familiar gray/brown, longitudinally ribbed seeds habitually positioned as a digestif by the cash register in your favorite Indian restaurant. Anise is an annual herb and needs a longish, hot, dry season to seed successfully, so, in cooler climes, it is advisable to start seeds in pots indoors in March and set them out when the soil is well warmed up. Otherwise, sow seed in situ in dry, light soil and a sunny spot early in April, thinning the plants to about a foot apart. When threshed out, anise seeds are easily dried in trays and jarred for future use. In ancient Rome, wedding celebrations customarily ended with an anise-scented Mustacae cake to aid digestion (and, one assumes, strengthen the coitus), so why not create your own festivity by mixing a handful of anise seeds into your favorite pound cake recipe?

Apple

Malus domestica

The apple tree was so anciently regarded that in British lore,

Avalon, where King Arthur was taken to die, translates to

Isle of Apples, and the Greek Elysium, where the worthy were

destined to spend their afterlives, to Apple Land.

A s we all know from that familiar Garden of Eden scenario, the apple is many millennia old, apple seeds having been found in Stone Age settlements in Switzerland dating to 8000 B.C. The tart wild crab apple (Pyrus malus), native to the Caucasus and Turkey, is thought to be the ancient ancestor of the lot, and the first trees to produce our familiar sweet apple are believed to have grown near the modern city of Almaty, Kazakhstan. The cultivated apple, Malus domestica, has most probably been under global culture since the dawn of nearly any civilization you can name, Alexander the Great having been known to have imported dwarf apple types into Greece from Asia Minor in 300 B.C.