Table of Contents

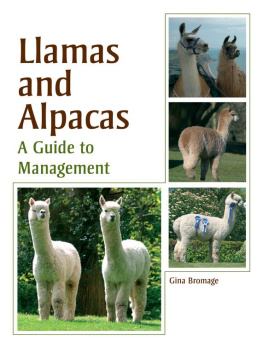

This book is for Barbara Kimmel and Jarelle S. Steinthank you, ladies, for your encouragement and endless patienceand for Deb Logan and Tina Cochran, whose love of lamas shines in Advice from the Farm.

INTRODUCTION

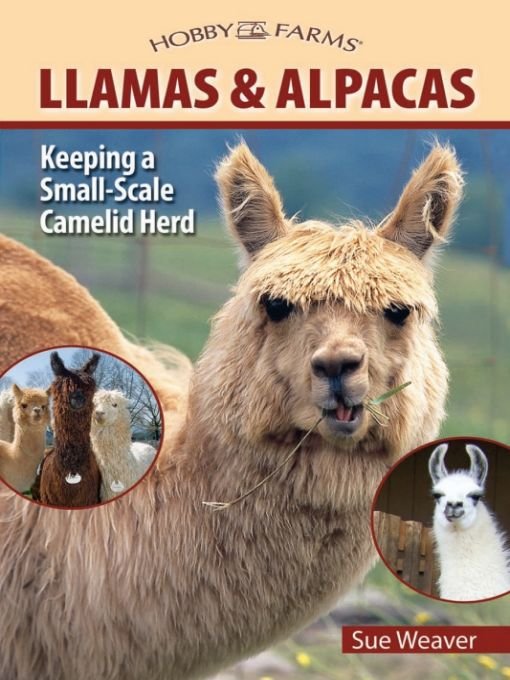

Why Lamas?

There has never been a better time than now to add llamas or fiber alpacas to your hobby farm menagerie. While top breeders still command impressive prices for the crme de la crme of the llama and alpaca world, its becoming easier to buy correct, registered llamas and alpaca geldings at pet, performance, and fiberowner prices.

Lamas (as llamas and alpacas are collectively called by those in the know) are fun to have around the farm. Their sweet, enchanting ways are sure to steal your heart. They cost little to feed and theyre easy to handle, even by folk who have never kept livestock before. However, this is not to say they dont have specialized needs: feed, appropriate shelter, proper fences, and quality veterinary care head the list.

And thats what this book is about: the ins and outs of buying, understanding, caring for, and enjoying hobby farm llamas and alpacas. Read on, and consider the facts before deciding if lamas fit your lifestyle. If so, do your homework, prepare your farm, and then go lama shoppingand welcome winsome, wonderful llamas and alpacas to your farm and into your heart!

CHAPTER ONE

Meet the Lama

The Llama is a woolly sort of fleecy hairy goat,

With an indolent expression and an undulating throat

Like an unsuccessful literary man.

Hilaire Belloc, More Beasts for Worse Children (London, 1897)

Llamas, alpacas, and their wild cousins, guanacos and vicuas, are collectively known as South American camelids or simply lamas. Most people associate llamas and alpacas with South Americas indigenous tribes, such as the ancient Incas, but few realize that the ancestors of these long-necked denizens of the Andes evolved in North America.

LAMA HISTORY AT A GLANCE

The oldest known protocamelid, a rabbit-sized, forest-dwelling creature known as Protylopus, appeared 40 to 50 million years ago during North Americas Eocene era. The first true camelids evolved 12 to 24 million years ago. These included the genus Paracamelus, the ancestors of todays Old World camels. Paracamelus migrated north across the frozen Bering Strait about 3 million years ago and evolved into one-humped dromedaries and two-humped Bactrian camels. Some 2 million years ago, two more genera began migrating south through Central America into the South American Andes Mountains: Paleolama (which later became extinct) and Lama. Lama eventually evolved into two modern species: Lama guanicoe (the guanaco) and Vicugna vicugna (the vicua).

Then, when referring to Pleistocene glacial epoch 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, a cataclysmic event occurred in North America that wiped out the remaining camelids there. Scores of other Ice Age mammals, such as the woolly mammoth and the saber-toothed tiger, also disappeared.

Archaeological evidence suggests that about 6,000 to 7,000 years ago, South American natives began domesticating wild camelids in the Altiplano (high plains) region of the central Andes Mountains, in areas now comprising southeast Peru, eastern Bolivia, and northern Chile and Argentina. The species that evolved there had to be tough and adaptable. A typical summer day in the Altiplano, which has an average altitude of 11,000 feet, may reach 70 degrees Fahrenheit, while nighttime temperatures may fall to 20 degrees or below. Between November and March, 90 to 95 percent of the years 10 to 28 inches of rain falls; the rest of the year is very dry indeed.

Did You Know?

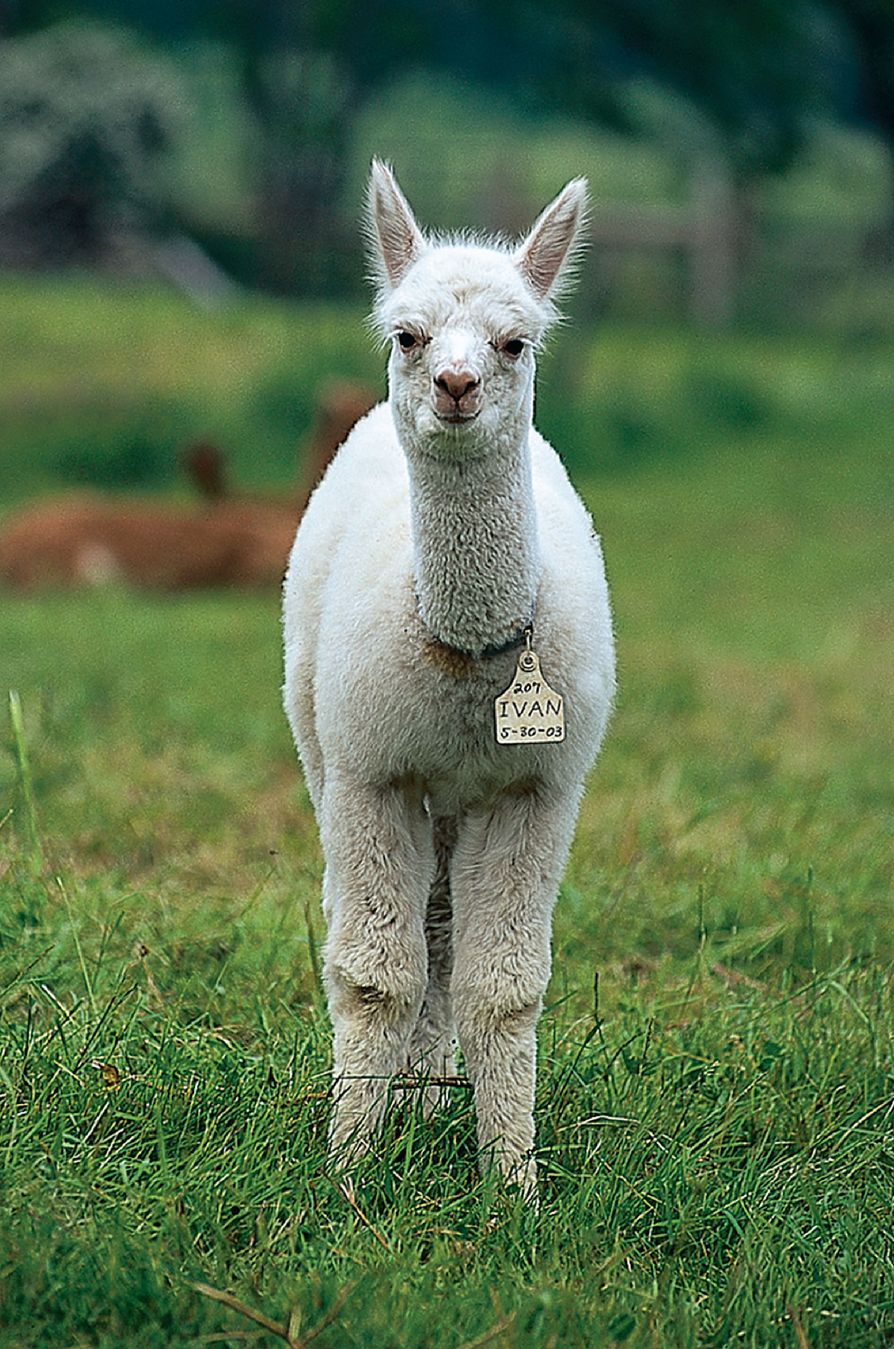

There were no wild llamas or alpacas. According to DNA studies conducted by American archaeozoologist Jane Wheeler and her colleagues, llamas are the domesticated descendants of wild guanacos, and alpacas are descended from wild vicuas.

As bison were to North Americas plains tribes, so lamas were to South Americas early indigenous peoplevital to survival. Llamas and alpacas supplied draft power, meat, fiber, grease, fertilizer, fuel, and leather. They were also precious for religious reasons, as evidenced by the many lama-shaped stone fetishes and conopas found at archaeological sites. Conopas, protective household figurines, had cavities in their backs that worshippers filled with offerings of intu (rendered fat from the chest of a llama) and coca leaves. So important did these symbols continue to be in native life that Spanish priests, seeking to convert the people by force in the seventeenth century, seized the conopas. Between 1617 and 1618, in the archbishopric of Lima alone, Spanish priests confiscated 3,418 conopas.

These llama-shaped bronze buttons follow the design of ancient effigies excavated at South American burial sites.

A Fortunate Foundation

Throughout prehistoric South America, llamas and alpacas were interred in human burials and buried en masse in important places. For instance, in the forecourt of the Chim capital city of Chan Chan in Perus Moche Valley (occupied from AD 1000 to 1400), priests interred hundreds of sacrificial llamas. Today, dried llama fetuses called sullus are buried under building foundations to bring good fortune, particularly in Bolivia, where an estimated 90 percent of families have at least one sullus buried beneath their homes. Construction workers refuse to work a job if there has not been a challa(blessing ceremony) held before work begins and a sullus buried underground at the work site. Sullus can be purchased for a small fee from stands at La Pazs famous Witches Market.Eachcomesblessedbyawitch and is wrapped in lana de llama, a multicolored llama wool fabric.

Naturally, lamas played an integral role in the lives of the great Incas, who flourished from the thirteenth to the mid-sixteenth century. By the end of the fifteenth century, the Incas controlled a 440,000-square-mile empire (covering much of present-day Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, and Chile as well as parts of Colombia and Argentina) composed of more than 10 million people. Because sheep didnt come until much later, with the Spanish conquerors, everyone from the Sapa Inca (the divine ruler) to the littlest peasant child wore clothing woven of camelid fiber. The peasant had garments made of everyday llama fiber. The nobility dressed in garments of campi, an ultrasoft fabric woven of vicua fiber; no one else was allowed to wear it on pain of death. High-ranking officials wore garments crafted of