Table of Contents

This book is dedicated to my husband, Steve, and our sons, Nick, Phil, and Joe:

Thanks for making it possible, and thanks for making it fun.

INTRODUCTION

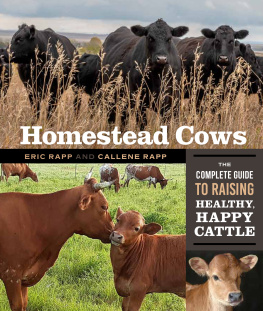

Why Beef Cattle?

Beef cattle are as much at home on the hobby farm as they are on the range. Adaptable to almost any climate and easy to manage and to market, they are well suited to any farmer with the pasture room and a hankering for a cowboy hat. Although beef cattle require a higher initial investment than any other traditional farm animal, except dairy cows, they require the least amount of daily maintenance.

Attention to the basics of raising beef cattle will reap rewards in the form of a freezer full of homegrown beef as well as extra cash from meat and calf sales. Where cattle are common, so are the auction barns, processing plants, and truckers that make it fairly simple to buy, sell, and process cattle. Americans love beef, so there is a ready market for beef cattle.

Theres another benefit to owning beef cattle: they can improve your land. This may come as a surprise, given the reputation cattle have acquired in certain quarters for overgrazing and destroying sensitive lands. But beef cattle are a tool, not a cause. The result depends on how the tool is wieldedjust as a hammer can be used to fix a building or to wreck it. Research and on-the-ground experience have demonstrated that, when properly managed, beef cattle can be a highly effective tool for restoring health to damaged grasslands and watersheds. On a hobby farm, well-managed beef can continually increase the richness of your soils, the biodiversity and lushness of your pastures, and the water quality of your ponds and streams.

Beef cattle will also enhance the view from your kitchen window. Every time I look out the window to see our cattle grazing the green slopes of our farm, hear bobolinks singing in our pasture, or prepare homegrown steaks for dinner, Im glad we have beef!

CHAPTER ONE

Beef Cattle: A Primer

Understanding the basics of cattle evolution, biology, and behavior can provide valuable insight into selecting the right cattle for your farm and caring for your new livestock. Heres a brief history of cattle and an overview of cattle types, breeds, and traits.

OUT OF ASIA, INTO THE WILD WEST

Bos primigenius, the massive ancestor of all modern cattle, stood up to six feet tall at the shoulder and wielded a spectacular set of horns, with a tip-to-tip span of up to ten feet. Herds of these wild prehistoric bovinesor aurochs as theyre commonly calledroamed throughout North Africa and most of Europe and Asia, following the melting glaciers of the last Ice Age northward. Between 500,000 and 750,000 years ago, long before humans appeared on the scene, the intimidating aurochs split into two distinctive subtypes, the taurine and indicine (or typicus and indicus) varieties of cattle. The humped, droopy-eared indicus multiplied in the eastern portions of the aurochs range, while the humpless taurine, whose ears stand out at the sides rather than flop, spread through the Middle East, northern Africa, and Europe. Their domesticated descendants are the droopy-eared indicus breeds that dominate Asia and are popular in the southern United States as well as the familiar taurine breeds that are common throughout Europe and North America.

Probably because they were so large, well armed, and willing to defend themselves, aurochs were rarely hunted by early humans and were domesticated after goats, sheep, and pigs were. But humans seem to have learned early on to love the taste of beef despite the difficulty of obtaining it. Eventually, they figured out that it was easier to raise, than to hunt, cattle and became ranchers. Cattle bones found in archaeological digs in southwestern Turkey show that between eight thousand and seven thousand years ago, the taurine-type cattle eaten by ancient villagers began decreasing in size, evidence of domestication. These early ranchers clearly selected small, docile animals less likely to charge their owners or disappear in the middle of the night.

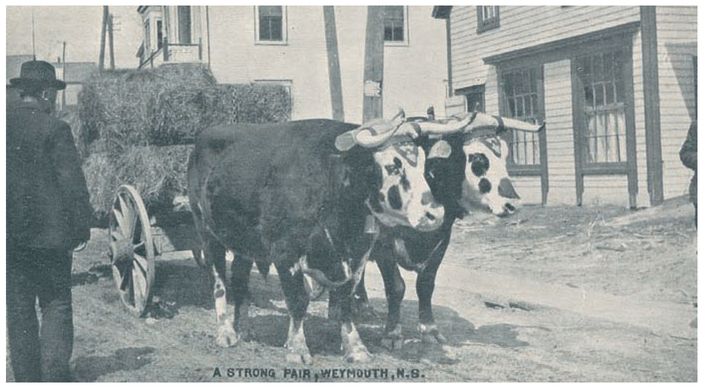

A pair of bulls carts hay through downtown Weymouth, Nova Scotia, in this old photo. Cattle have historically been used as draft animals as well as sources of meat and leather.

While Middle Eastern farmers appear to have been the first to domesticate cattle, farmers elsewhere probably did so not long after. Many researchers believe indicus-type cattle were domesticated separately in Asia. A more controversial theory argues that taurine-type aurochs were also domesticated separately, by North Africans, and later mixed with immigrant indicus to give rise to the distinctive sanga cattle breeds of Africa.

Early Middle Eastern farmers used cattle solely for meat and leather and kept far fewer cattle than they did sheep and goats. When humans began migrating into the heavily forested and much colder regions of northern Europe, they quickly found themselves much more dependent on cattle. On the move north, goats could not pack as many of their owners possessions on their backs as cattle could, and once people arrived in the new land, neither sheep nor goats were of much use in clearing forests or pulling plows in the heavy soil. As farming spread north, cattlewhich are not fussy eaters and not overly bothered by predators and actually seem to like the coldquickly became the most important livestock species. Oxen (castrated adult male cattle) became northern Europes primary source of transport and farm power. They remained so until about two hundred years ago, when horses and then the internal combustion engine took their places in most regions.

By three thousand years ago, cattle keepers from Egypt to England had figured out that a cow that pulled a plow or a cart could also furnish milk for the family. Thus the dual-purpose cow and the dairy industry were born. Cows and oxen no longer able to work provided their owners with a large amount of highly nutritious and palatable beef and hides for leather goods.

When English and Dutch settlers brought their cattle to North America in the early 1600s, they adapted their ways of keeping cattle to their spacious new environment. All along the East Coast, cattle not needed for milk or labor were turned into the woods for the summer and rounded up in the fall. Each animal had its ear notched in a way particular to its owner, who had to register his brand with the town officials. In the fall, excess cattle were assembled in herds and a drover hired to walk them to the freshmeat markets in big towns such as Boston and Philadelphia.