Contents

Chapter One:

Chapter Two:

Chapter Three:

Chapter Four:

Chapter Five:

Chapter Six:

Chapter Seven:

Chapter Eight:

Chapter Nine:

Chapter Ten:

Chapter Eleven:

Chapter Twelve:

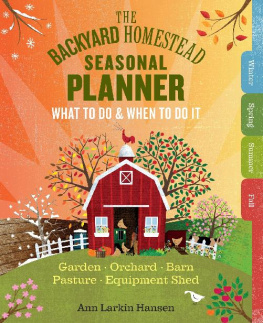

Preface

When my family and I first moved to this farm, I wanted to do it all: garden, keep an orchard and bees, grow field crops, raise livestock and poultry, have my own firewood and timber. It was a steep learning curve, though my job as a reporter for a weekly farm newspaper helped a lot, since it took me to several hundred farms and introduced me to many farmers and agricultural professionals. There were plenty of mistakes and some outright failures along the way, but I did learn, and my husband and I are still here and still happy, rejoicing in homegrown food and even making a little money most years.

The three biggest things Ive learned over the past 25 years are:

- You cant do it all at the same time if you have a small budget, a family, and outside job obligations not if you want a decent life and good family relations.

- You dont need to do it all. What does work nicely is to try different enterprises pigs, bees, timber harvests, whatever over the years to discover what you like best, whether they fit together well, and what most benefits your family, your land, and your budget. Keep what works.

- Doing a thing in its proper season when it would naturally occur, or when conditions make the job most efficient and comfortable is how you spread the work more evenly through the year. This is what makes it possible to get it all done and still have some leisure time.

This book is about timing, as important an aspect of raising plants and animals as any other. Bits and pieces of information on when to do farm-related tasks are widely available in gardening calendars, vaccination schedules for livestock, discussions of when to prune trees and plant crops, and so on. This book combines all of this information to create a seasonal calendar for the most common enterprises found on small diversified farms, in a way that spreads the work appropriately and more or less evenly and can be understood and applied anywhere in the temperate zones of this continent. This book assumes that you wish to work with natural processes instead of against them, and so the calendar of seasonal tasks in each chapter excludes the use of synthetic chemicals.

Every rural acreage is different in what and how and when to do things, because every piece of land is different and so is every landowner. For that reason, no one else (and especially no book) can possibly tell you precisely what and how and when you should do things on your place. A book tells you what to look for and which questions to ask. You have to figure out the answers.

This book is just a beginning; it gets you to the starting line. From there you have to run the course: do the thinking and planning and experimenting over the years to fill out the details of your own personal farm calendar. The people who do that think and plan and experiment are the ones who thrive.

Introduction

Defining the Seasons

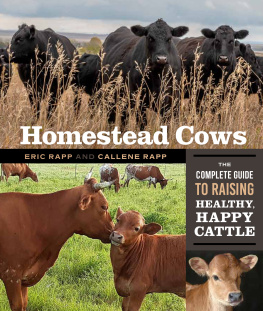

Seasons vary a lot, year to year. Theyre wet or dry, cold or warm or hot, early or late. Just now were in the middle of the most drawn-out mud season, otherwise known as late winter, that Ive ever seen, and its been a challenge to keep the cattle even reasonably dry.

The timing and length of the seasons differ strikingly across temperate North America, but the seasons themselves are similar enough that we recognize the same broad characteristics. Winter is a time of cold and no plant growth; summer means heat and long days. Spring is the transition from winter to summer, and fall the transition from summer to winter. Each season slides into the next; only rarely is there a sudden shift. In the most southern states, winter almost disappears and summers are hot enough to keep cool-loving plants from growing; in the northern tier of states, summers are short and relatively cool and the growing season isnt long enough for tomatoes and other long-season plants to mature when started outside.

As a culture, weve gotten into the habit of looking at the calendar to determine planting times and other such decisions, no matter whats going on outside. But a few generations ago, instead of looking at the calendar, farmers and gardeners looked at what the local plants and birds and other wildlife were doing a much more accurate indicator considering how different seasons are from year to year. Using plant growth and wildlife activity to identify how far along you are in the year is called phenology, and it is a highly useful study for anyone who grows crops or raises animals.

But phenology is a very local study, since seasonal indicator species vary widely across various regions. Spring in the Southwest has a different cast of native characters than spring in the Northeast. The signs can vary even across small areas. Our friends just 15 miles to the south know that sprouting skunk cabbage means winter is coming to an end, but Ive never seen it in our neighborhood. I watch for returning red-winged blackbirds instead. Phenology cannot define what makes a season across the entire temperate zone of the continent.

Useful Seasonal Indicators

There are, however, some precise and fairly universal indicators of the different seasons that apply no matter where you live.

Soil and air temperatures. These can be measured with air and soil thermometers (soil temperature is measured at a depth of 3 to 4 inches) or by keeping an eye on what local farmers are doing. There are three crops grown throughout North America corn, wheat, and alfalfa that, no matter where they are planted, germinate and grow best with specific soil and air temperatures. Wherever you are in the country:

- Spring wheat goes in the ground in early spring.

- Most farmers plant field corn in the middle of spring.

- The first cutting of alfalfa for hay occurs in late spring into early summer.

Rate of growth in warm- and cool-season grasses. This is a second good and widespread indicator of the season. Except for the first cutting of alfalfa, harvest times are not reliable indicators crops get harvested when farmers judge that theyre mature, more so than according to the season.

In this book, I have used soil and air temperatures and grass growth as indicators to generally define 12 seasons: an early, middle, and late period of each of the 4 major seasons. This level of detail allows for a much more specific discussion of what should best be done at a particular time of year, and why.

Soil temperature is measured with a soil thermometer at a depth of 3 to 4 inches.

Warm- and Cool-Season Grasses

Cool-season grasses commonly used for forage: Tall fescue, Kentucky bluegrass, orchard grass, redtop, smooth bromegrass, timothy

Warm-season grasses commonly used for forage: