Contents

Acknowledgments

Both this book and our mechanical knowledge owe a great deal to the talented friends and mechanics we have known in our years of dealing with equipment. Wed especially like to thank Lawrence Reynolds III, Arlyn and Kevin Rediger, and Tim Stanton, along with the guys at Badger Sales, Swoboda Implement, Tractor Central, and Baribeau Implement. Last, Ann is still grateful to our old neighbor, Gary Bathke, who spent a summers evening long ago installing a cut-off switch in the Farmall so that she didnt have to jump-start it every morning.

Any mistakes are, of course, our own.

Introduction

Equipment amplifies our efforts so we can do more work with less time and muscle. A generation ago, farmers and homesteaders learned from their older relatives how to maintain and repair equipment, but few of us now have that resource. We hope this book helps to fill that gap.

Farm equipment falls into three general categories: human powered, small scale, and large scale. Maintenance and repair of human-powered tools requires little instruction; all thats needed is occasional cleaning, tightening, sharpening, and applying linseed or tung oil to the wooden parts. Large-scale equipment, from 100-horsepower-plus tractors to 36-row corn planters, is generally beyond the needs or financial means of the small-scale farmer.

Therefore, this book covers the engines and implements that fall between human and huge, the kind found on most small-scale farms, and which we own and have learned to maintain and repair through more than 20 years on our own farm.

A bad mechanics favorite tool is a hammer; and his second favorite tool is a bigger hammer. A bad mechanic understands the true meaning of cobbled together, and his solutions are based on colorful language instead of knowledge. A bad mechanic believes safety first simply takes too much time.

A good mechanic takes pride in his work. He is systematic and stays organized; maps out a solution before starting the trip; anticipates pitfalls; understands how something is supposed to work so that he can recognize any problems; and asks for help when its needed.

Friend, farmer, and repairman Butch Reynolds

Chapter One

Parts

The various equipment available to the small farmer is built from a fairly standard palette of part types. Understand the function of each type of part and see how the parts are assembled; you can then reason through how power is moved from engine to application. Learning how to keep equipment working follows logically from this starting point, so well begin by discussing the types of parts common on farm equipment fasteners; wheels and shafts; bearings and bushings; and hoses and lines and their functions.

Each type of part comes in a variety of permutations; for example, not all springs look like a coiled wire. If possible, read this chapter with a piece of equipment in front of you so you can get a real-life look at types of parts; illustrations and text are great starting points, but getting your hands on metal is necessary to really grasp how things fit together.

Fasteners

Parts that hold things together are employed whenever you need to attach an implement, disassemble something to do general maintenance, or make a repair. The most common types of fasteners are bolts, rivets, clips, spring clips, keys, cotter pins, hose clamps, springs, shafts, U-joints, and hitch pins.

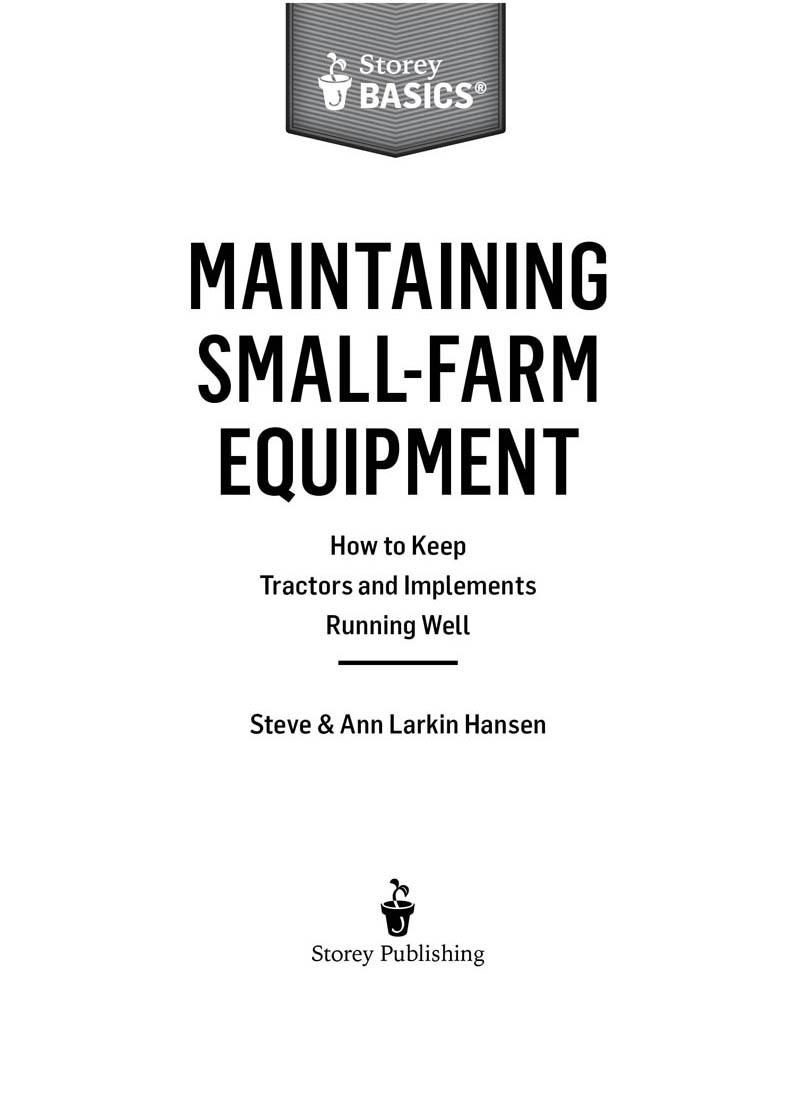

Bolts, Nuts, and Washers

Bolts are threaded metal shafts that are blunt on one end and have a head on the other. To hold them in place requires screwing a nut onto the shaft, or screwing the bolt into a threaded recess. Nuts are either standard or locknuts, which are designed to provide extra holding friction where theres constant vibration. Washers are used when a hole is bigger than the bolt head or nut, or to hold the bolt head or nut farther from the hole to shorten how much shaft sticks out the other side. Split or star-type washers have the same function as a locknut.

Four Important Things to Know about Bolts

- Bolts are sized by the length and thickness of the shaft and defined by thread count (coarse or fine) and head type: for example, a quarter-inch by two-and-a-half-inch (" x 2") fine-thread hex-head bolt.

- Bolt heads (and threads, nuts, and shaft sizes) are made to either metric or US measure, so youll need either US or metric socket wrenches (see on tools) or, more likely, both.

- Bolts come in varying degrees of hardness. Numbers 2, 5, and 8 bolts (from softest to hardest) are the grades most commonly used in machinery. Hardness is indicated by the number of lines on the head: no lines for grade 2, three lines for grade 5, and six lines for grade 8. Metric bolts are marked with the numbers 8.8, 10.9, and 12.9 for equivalent grades. When you need to replace a bolt, the new bolt ideally should be of the same hardness.

- The compressive friction of the bolt head and the nut against the pieces they are fastening together is what gives the connection strength; in other words, loose bolts wear and break more easily than tight bolts.

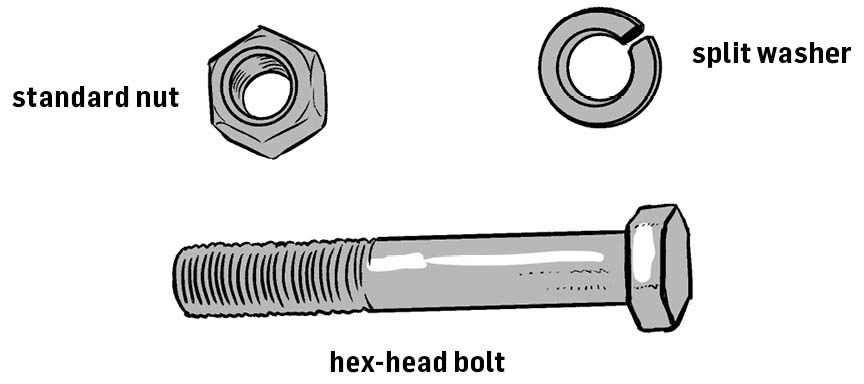

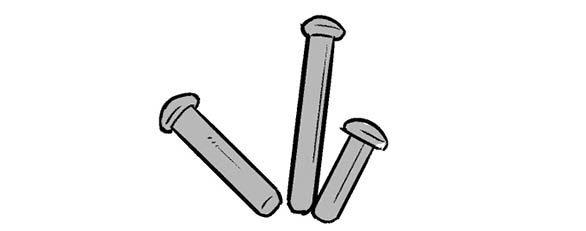

Rivets

Machine rivets have smooth shafts, half-round heads, and a very low profile; theyre used to hold parts moving through tight spaces. Removing and installing rivets is done with a riveting tool. You will run across rivets mostly on older equipment. Since rivets can be fussy to replace when worn or broken, if there is room to substitute bolts it makes future repairs simpler.

rivets

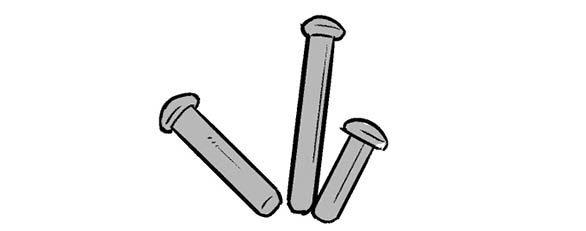

Clips, Cotter Pins, and Keys

Clips of various sizes and shapes are used to hold and align parts where there wont be too much force and are designed for quick insertion and removal. The most common is the hitch pin clip, which is pushed through a hole in the bottom of a hitch pin (which connects an implement to the tractor) and keeps the pin from bouncing out.

hitch pin and clip

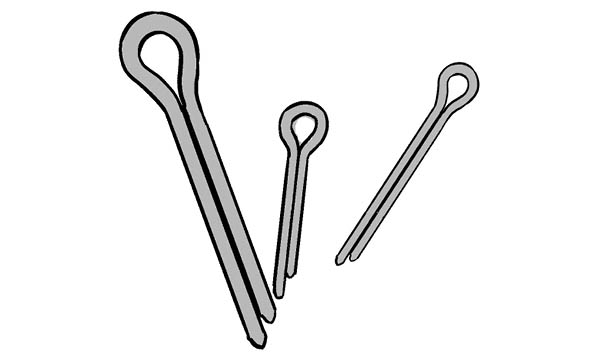

Cotter pins are a specialized type of clip, made of soft metal so they will break under unusual force and spare the more expensive parts they hold together. They're also used to lock nuts in place. They are intended to stay in place until they fail.

cotter pins

Keys are used to lock together a shaft and pulley or shaft and sprocket. Short canals or grooves are machined on the exterior of the shaft and the interior opening in the pulley or sprocket, and the key (either rectangular or half round called a half-moon or Woodruff key) slips into the grooves and locks the two parts together. A