I wish to express my gratitude to the readers of University of Toronto Press for their close reading and valuable suggestions and to Richard Ratzlaff for his encouragement. I would also like to thank Lena Anime in the National Archive in Stockholm and Christina Sandahl in the National Library of Sweden for their assistance in supplying me with pertinent materials.

Introduction

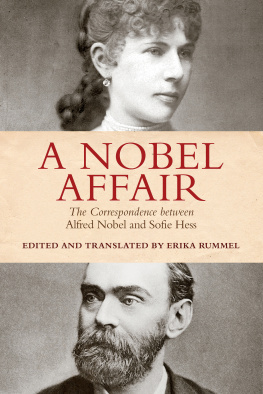

The letters exchanged between Alfred Nobel and Sofie Hess, his Viennese mistress, span almost two decades, from 1877 to 1896. The couple wrote to each other in German.

After her lovers death, Hess offered to sell the collection to the Nobel Foundation, perhaps because she was dissatisfied with the annuity granted her under the terms of Nobels will.

During his lifetime, Nobels fame rested on his inventions and on his success as a businessman. His correspondence may therefore be regarded as a primary source for historians interested in nineteenth-century economy, science, and technology. The letters Nobel wrote to Sofie Hess do indeed contain references to his scientific work and his business dealings, but they are too vague to contribute significantly to what we already know from other sources. They do, however, offer important new insights to readers interested in the biographical details of his life and to scholars of nineteenth-century social history. The fact that the Nobel Foundation paid Hess for the letters and kept them private for decades is in itself an indication of their historical significance. The Foundation was intent on reinforcing Nobels image as a high-minded visionary and philanthropist. His correspondence with Hess, by contrast, shows up his all-too-human failings. Reading his letters, we encounter a man obsessed with work, whose tireless pursuit of innovation and business ventures took a heavy toll on his physical and psychological health, a man who was paranoid, cranky, sarcastic, bigoted, and old beyond his years. The discretion exercised by the Foundation led to misinterpretations, such as the suggestion that his relationship with Hess was platonic untenable on the evidence of their letters and to a one-sided picture of Nobels personality.

The correspondence sheds light not only on Nobels character and his relationship with Hess, but more generally on the position of mistresses in nineteenth-century Europe. The lives of women supported by wealthy bourgeois remain a somewhat neglected area of research, lost between the well-documented subjects of prostitution Although Hess had no independent source of income and fully relied on Nobel to look after her expenses, their relationship cannot be described simply as an exchange of sex for money, such as occurs between a prostitute and her client. Indeed, Nobel continued to support Hess after their physical relationship ended, and Hess in turn was loyal to him for many years until he himself suggested she look for another man and find a suitable marriage partner.

Unlike the lives of the great maitresses of Paris, which are generally reflected in the comments of others or described in carefully construed autobiographies referring to events long past, the lives of Hess and her lover are given immediacy through letters written in real time. It is tempting to compare (or rather, contrast) their correspondence with another collection: the letters exchanged between Victor Hugo and Juliette Drouet, his Muse and mistress. Such a comparison is suggested by the fact that the two men, Nobel and Hugo, were on visiting terms and familiar with each others life and work.

Like Nobel, Hugo tried to hide his lover away and isolate her in a rented apartment to keep the affair out of the public eye (and in Hugos case, out of his wifes eye). How scandalous was it for a man to have a mistress in nineteenth-century Paris? It seems the position of the kept woman was ambiguous. Alfred Delvau, a contemporary of Nobel and Hugo and the author of Les Plaisirs de Paris, remarks that men were proud of their conquests. Going to the Bois was an excellent occasion to show off their horses or their mistress but only if the woman of their choice was la mode, that is, was chic and had a laughing grace of manner.

Nobel made Sofie Hesss acquaintance relatively late in life, at the age of forty-three. He was born in Stockholm in 1833, the fourth son of entrepreneur and inventor Immanuel Nobel and his wife Carolina Andrietta. He and his siblings grew up in poverty until the elder Nobel emigrated to St. Petersburg and prospered there as a manufacturer of military and construction equipment. Alfred therefore received an excellent private education. He took a special interest in chemistry thirty years, he obtained more than three hundred patents, among them one for blasting oil in 1863.

Nobels brothers, Ludvig and Robert, remained in Russia and continued with the manufacture of military equipment. In 1873 they acquired oil fields near Baku and in 1879 they founded Branobel, an oil company, in which all three brothers held shares. he moved to San Remo on the Italian Riviera, where he died in 1896.

Designed originally for industrial blasting operations, dynamite was more commonly employed in warfare, earning Nobel the sobriquet merchant of death,

Nobel often complained that he was lonely and friendless, and in later years tried to blame Sofie Hess for his isolation: You have so tarnished my name that I, who do nothing but work and help others, am discredited and must live an isolated life. Nobel had great affection for his mother, but apart from her, Sofie Hess was the only woman who could claim to have a close personal relationship with him.

Sofie Hess (18511919) was of Jewish parentage. She was the oldest child of Heinrich Hess, a dealer in timber from Celje (Slovenia) and his wife Amalie. Nobel met Sofie Hess in 1876 in Baden (near Vienna), where she worked in a flower shop.

For the next fourteen years the pair lived together after a fashion. Sofie Hess called it living together at any rate, although she was

Taking the waters had been an aristocratic pastime at first, but in the nineteenth century the practice was imitated by wealthy bourgeois.