One wet Friday morning in the spring of 2000, I found myself in the Dorset market town of Dorchester to give a radio interview about a book I had written on the politico-diplomatic events of 193940, called Hidden Agenda.

As I sat in the tiny broadcast studio staring at the microphone, my head clamped within a hefty pair of headphones, I little realised that within the next twenty minutes a question asked by a DJ tucked away in a BBC broadcast studio in Southampton would occupy my life for the next two years, cause me to collect many thousands of documents from as far afield as Germany, Japan, the United States and Russia, or travel many thousands of miles to interview experts and witnesses from as far afield as a nursing home in Glasgow, to a mansion in Bavaria, an apartment in Stockholm, and a townhouse on the outskirts of Washington DC.

I took a sip of water from a plastic cup, blissfully unaware that a mysterious element of the Second World War would soon prove so magnetic to my curiosity that before the end of the week I would begin a hunt for documents and people who might help me solve a mysterious affair that had taken place over sixty years ago

Suddenly the headphones cracked into life and a disembodied voice greeted me jovially: Hello. Are you there, Mr Allen?

After a brief acknowledgement from me, the voice pronounced Great! Im cutting you in now and with that music that was being broadcast to the south of England burst loudly from the headphones for a few brief seconds, before almost immediately beginning to tail away again.

Wasnt that nice, just the sort of thing for a wet summers day, the DJ announced to his audience. Now, as I mentioned earlier, Ive been joined this morning by Martin Allen, who has just written a book on the Duke of Windsor which throws new light on events at the start of the Second World War. Hello Martin

And so the interview got under way, with much banter from the distant DJ, and some searching questions as well for he had evidently read the book and wanted the most out of the interview.

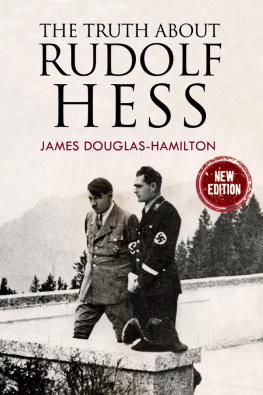

About halfway through the interview, whilst we were discussing the Duke of Windsors time in Lisbon, where surreptitious communication had begun between the German government and Britains former King at loose on a continent aflame with war, the DJ pointedly asked: Given that the Duke of Windsor knew Hess, is it correct to say he was connected to Hesss flight to Britain in May 1941?

I paused, my immediate inclination was to answer yes, but in the nanosecond between the DJ asking his question and my considering the answer, I suddenly realised, No, it cant be connected to Windsor. Hesss flight to Britain was nearly a year later, and the Duke of Windsor had been in the Bahamas for much of that time. What then was the answer? I sidestepped the question, declaring that the Hess problem would not easily be solved until all the documents on the matter were released, and the interview duly progressed in another direction.

I do not really remember the drive home that day, for my mind was back sixty years in those dreadful dangerous days of 194041, when Britain had stood alone and fought desperately for her very survival. Ignoring the heavy traffic and pouring rain, I found myself mentally sifting through the considerable Foreign Office and Intelligence evidence I had accumulated to write my last book, sure that a clue to what took place was there somewhere, yet positive it would not be the full answer.

Rudolf Hesss flight to Britain had taken place on the night of Saturday 10 May 1941, 10 months after the Duke of Windsor had departed Portugal aboard the SS Excalibur bound for the Bahamas where he was to become the colonys new Governor. That the Windsors did not want to go, considered the Bahamas little more than a gilded cage with golden sands, a St Helena of 1940 as Wallis called it, was without a doubt. However, I also knew that despite still feeling himself deserving of some greater task in life, the Duke of Windsor had lost his importance to the Germans by then and become superfluous to their needs. In addition, with the Duke of Windsors departure from war-torn Europe, Ribbentrops potential as a man capable of delivering that illusive peace deal Hitler wanted had taken yet another severe knock as well, for the German Fhrer had finally realised that his Foreign Minister was not up to the job of ending the war with Britain. Therefore, I concluded, Ribbentrop, together with the Duke of Windsor, was unlikely to have been connected to Hesss flight to Britain in May 1941.

What, then, was the answer?

To uncover the facts behind a wartime event that is in many respects still secret is extremely difficult, for a substantial number of key documents on this element of the Second World War have never been declassified. Against such a climate of secrecy, this paucity of available evidence, it can be almost impossible to uncover the truth, and it has to be said that one eventually learns new ways to uncover the facts.

When I had written Hidden Agenda, a French-American named Charles Bedaux had proven to be the key to revealing the Duke of Windsors secret activities during the Phoney War. I therefore concluded that what I needed was a new version of Bedaux; someone who had been privy to the events of 1941, but who might have escaped undue attention. Having given some thought to the Hess mystery, it occurred to me that there had been another such person, someone who had been privy to Hesss innermost thoughts during the 194041 period his close friend and personal foreign affairs advisor, Albrecht Haushofer.

What made me realise that Albrecht Haushofer might become my key to unlocking the Hess mystery was the knowledge that at the end of the war the Haushofer family itself had become a source of mystery. Great efforts had been made by Allied intelligence to investigate both Albrecht Haushofer and his father Karl Haushofer, but more intriguing still was the knowledge that certain of their papers had vanished from Allied custody. A sure sign someone had something to hide.

And so I began the chase again a search of the worlds archives, the tracking down of persons who had worked for the British and German Foreign Ministries, associates of Haushofer, Hess, Hitler, and Ribbentrop too; those privy to certain other secret events of 1941, and finally, the not insubstantial task of reading many thousands of pages of evidence.

Slowly by not only examining the obvious evidence, but also looking for the unobvious and spending a great deal of time pursuing dead-ends the Rudolf Hess mystery began to give up its secrets, and what was revealed was not at all what I had expected

Martin A. Allen

April 2002