Table of Contents

ALSO BY JOHN SZWED

Space Is the Place: The Life and Times of Sun Ra

So What: The Life of Miles Davis

Jazz 101

Crossovers: Essays on Race, Music, and American Culture

To

Roger D. Abrahams

and

The Department of Folklore and Folklife,

University of Pennsylvania

1962-1999

INTRODUCTION

The first time I saw Alan Lomax was in November 1961 at a meeting of the Society for Ethnomusicology, an academic group then too new to have developed its own orthodoxies. They were still debating the definition of music, the meaning of dance, the function of song, all with a sense of wonder and urgency. The founders of the discipline were all thereCharles Seeger, Mantle Hood, Alan Merriambut the doors were still wide open.

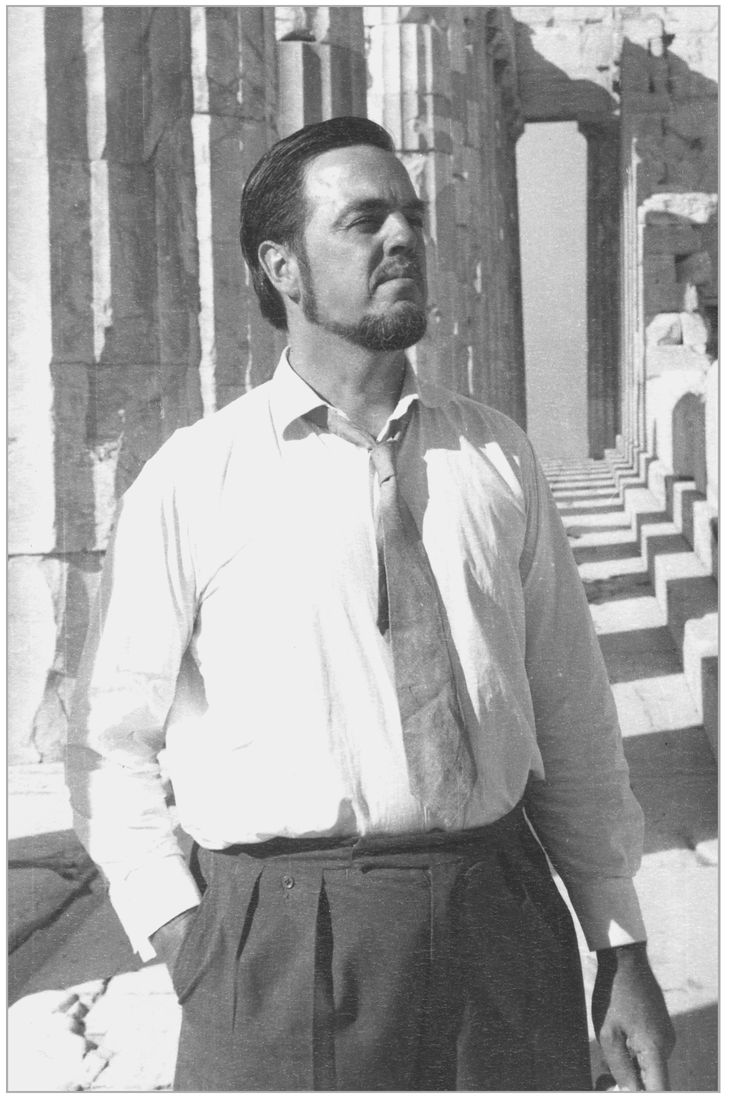

I was a graduate student new to the world of folklorists and ethnomusicologists and eager to connect with them somehow. The big event that night was a concert of African music by the Nigerian drummer Olatunji, who had added to his group some of the members of the Sun Ra Arkestra, and the mixture of the two musics had the scholars puzzled. As the audience filed out, I saw Lomax talking with two men who I later learned were Colin Turnbull and Weston La Barre, not your everyday anthropologists. I knew it was Lomax despite never having seen a picture of him, because his slightly genteel Texas accent drifted to the back of the room. He was big, though I suppose not as big as he looked, in an ill-fitting blue suit, with his collar and tie askew. Well-dressed enough to be a Bible salesman in Alabama, I thought, but missing the mark of a successful academic. Later, in the high sixties, when I knew him better, it was he who chastised me for my choice of clothinghe told me that government-grants people and highly placed folks of color would not take me seriously. (My one effort at dressing up for something or other amused him, and he said my tan suede jacket and bright tie made me look like a southwestern TV station manager.)

I must have been staring at him that day in the theater, for as he passed me, stepping over rows of seats, he declared as if it were the days headline, Pygmies are a baseline culture, and went on his way. He sounded like some nineteenth-century grand theorist speaking from a higher plane, with a scarcely concealed moral program and no sense whatever of then-trendy cultural relativity. Once I had heard him speak at length, I began to wonder what kind of folklorist was this, if thats what he was, with no particular interest in the text of a song or a tale. It turned out that he was speaking comparatively of other levels of art, of humanitypreverbal levels, where bodies interact in front of a cross-cultural tableau, and where art emerges from deeply encoded but virtually nonconscious behavior.

Later, I worked for Alan on occasion, though never for money, as it was understood that he was always short, and I had a day job. He was infinitely patient with the novice, answering questions more fully than was required, with tales of this or that epiphany on the shores or in the swamps of this or that community, of sheriffs with bowie knives who threatened to cut his throat if he ever came back to their county. His stories of working with Zora Neale Hurston were rich and full of his admiration for her fearlessness while doing fieldwork among hoodoo practioners. When I asked him for advice about graduate study, he suggested I drop out and instead do as he had done: seek the company of the very best people in the fields that interested me.

Whenever Alan asked me to join him for lunch or dinner, it was always someplace with well-etched character, though sometimes with marginal food. It might be a bar where the bartender was also waiter, cook, and cashierlike it used to be. Or a tiny Chinese restaurant where he felt free to order something not on the menu. In conversation, Alan could shift instantly from deadly serious or highly focused to mock folksy or laughing at the absurd, his eyes always a clue as to what was coming. When he called me, usually late at night, it was never just to talk, but because he wanted somethinga reaction to a new research project, maybe a suggestion of a name of someone who might work with him on it. Though the request was unspoken, I always knew he was asking me if I would do it. And I wondered how many he had called before me.

Sometimes what he had dreamed up could cost great sums of money, or simply be impossible at the moment. One idea was a plan to sell the television networks on a half-hour prime-time program that featured old people being old peopletalking about their lives, maybe sharing secrets, making connections to tradition, performing wisdom and maturity, he said, something like that. He spelled out the details of what would be a kind of homespun reality show. When I cautiously suggested that this would be impossible to sell in the high-profit atmosphere of the media, he pointed to a little vase on the table with a few tired daisies in it and said, This is not much of a vase, and the flowers arent much. But if you knew that you could count on finding this vase and those flowers on the table every night for years to come, wouldnt that be something? He could be hard to argue with.

His enthusiasm was boundless and seemed to grow with age. His drive to celebrate life in all its diversity and to see, taste, and hear everything was astonishing. If you mentioned the blues, he could tell you that Son House was the greatest folk musician in the Western world. Tell him that you were on the way to Trinidad, and hed say that a man named Nassus Moses who played a one-string fiddle and lived in a hut in the suburbs of Port of Spain was the greatest folk musician in the Western world. And in one sense or another, they always were the greatest at something or other.

One night he suggested that several of us go to the Village Gate in New York to see Professor Longhair. It was a bit surprising to hear him praising the brilliance of New Orleanss sainted rhythm and blues pianist, since we werent aware that he kept up with that sort of thing, but we happily followed him to the club. Since we were late, we squeezed our way in and found seats wherever we could. When Fess opened his first set with Jambalaya, Longhairs rolling, blues rumba- flavored revision of Hank Williamss revision of Cajun music, backed by a Crescent City band of beboppers and funksters, I expected a post-gig lecture from Alan about taking creolization too far. But then I felt something brush by my leg, and when I looked down there was Alan crawling on the floor toward the bandstand so as to stay out of peoples vision. When he reached the stage he knelt there, his hands on the edge of the stage like a supplicant Kilroy, until the set was over. As he came back to our table, he cried out over the crowd, Greatest folk musician in the Western world, then followed it up with a letter to the Village Voice spelling out the New Orleans piano lineage, how Longhair was the roots of Fats Dominos style, and thus basic to the history of rock and roll, if not the world.

To those who knew Alans work only from his songbooks he seemed to be the pied piper of the folk, a kindly guide for a nostalgic return trip to simpler times. But he might have thought of himself as spokesperson for the Other America, the common people, the forgotten and excluded, the ethnic, those who always come to life in troubled timesin the Great Depression, in the rising tide toward World War II, during the postwar anti-Communist hysteria, and inside the chaos of the era of civil rights and counterculturalismthose who could evoke deep fears of their resentment and unpredictability. At such times folk songs seemed not so much charming souvenirs as ominous and threatening portents.