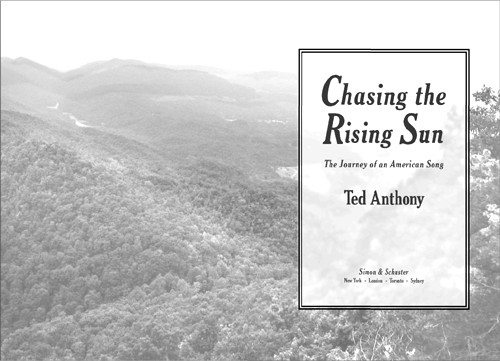

SIMON & SCHUSTER

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2007 by Edward Mason Anthony IV

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-800-456-6798 or business@simonandschuster.com.

Designed by Paul Dippolito

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-7898-0

ISBN-10: 0-7432-7898-4

eISBN: 978-1-416-53930-8

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

Courtesy of Ted Anthony: 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 16, 19, 20, 21

Courtesy of the AP: 2, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29

Photo courtesy of Homer Callahan: 7

Photo courtesy of The Moaners: 14

Courtesy of Eva Ashley Moore: 4, 11

Photo courtesy of Melissa Rayworth-Anthony: 15

Courtesy of Georgia Turners children: 1, 17, 18

Dedication

For my father, Edward Mason Anthony Jr., who first sang me the old songs.

For my son, Edward Mason Anthony V, who is just starting to learn them.

And for Georgia Turner Connolly, who deserved better.

Contents

There is a house in New Orleans

they call the Rising Sun.

Its been the ruin of many a poor girl

and me, O God, for one.

If I had listened what Mamma said,

Id a been at home today.

Being so young and foolish, poor boy,

let a rambler lead me astray.

Go tell my baby sister

never do like I have done,

to shun that house in New Orleans

they call the Rising Sun.

My mother, shes a tailor;

she sold those new blue jeans.

My sweetheart, hes a drunkard, Lord, Lord,

drinks down in New Orleans.

The only thing a drunkard needs

is a suitcase and a trunk.

The only time hes satisfied

is when hes on a drunk.

Fills his glasses to the brim,

passes them around

only pleasure he gets out of life

is hoboin from town to town.

One foot is on the platform

and the other one on the train.

Im going back to New Orleans

to wear that ball and chain.

Going back to New Orleans,

my race is almost run.

Going back to spend the rest of my days

beneath that Rising Sun.

THE RISING SUN BLUES, AS ASSEMBLED BY ALAN LOMAX FROM FIELD RECORDINGS MADE IN EASTERN KENTUCKY IN SEPTEMBER AND OCTOBER 1937.

Introduction

you never can tell what goes on down below. This pool might be bigger than you or I know! This MIGHT be a pool, like Ive read of in books, connected to one of those underground brooks! An underground river that starts here and flows right under the pasture! And then well, who knows?

DR. SEUSS, MCELLIGOTS POOL

Tell me, man, which way to the rising sun.

OLD BLUES, SUNG BY HENRY SIMS

I do not belong to my own generation.

When I was born in the turbulent, musical spring of 1968, my father was forty-five years old and my mother forty-three. My sisters, born in 1947 and 1951, were grown. Though I grew up Gen-X in suburban Pittsburgh, my friends parents were my sisters ages. Generationally, I was a Baby Boomer. I look back more easily to American yesterdays because, I think, so much of it seems real to me.

And it has shown in my music.

The songs that played within my house were different from those that came from outside. When my mothers ubiquitous transistor radio, tuned to KDKA-AM, would pipe in Billy Joel, Fleetwood Mac and the Bee Gees, I absorbed them all. But the sounds coming from the family room, from my fathers floor-model Magnavox phonograph, were so different as to be barely recognizable. Glenn Miller. Benny Goodman. Tex Benecke. And from my fathers own fingers, on the Grinnell Bros. upright piano, the music reached back even furtherdeeper into a distant history I didnt recognize as such just yet. Scott Joplin rags. St. Louis Woman. Oh, Susanna and Old Folks at Home and There Was an Old Woman Who Swallowed a Fly. Occasionally my mother would chime in with Ive Been Workin on the Railroad.

Best of all was bedtime, when he would sit on the edge of my bed and sing. He could never say where he learned most of the songs, which I realize now is a standard characteristic of folklore. Some, hes sure, he got from his father or his grandmothers. Some he probably just heard. But he remembered them for me.

My grandfathers clock

was too large for the shelf,

so it stood ninety years on the floor.

One dark night, when we were all in bed,

Old Mother Leary put a lantern in the shed.

And when the cow kicked it over,

she turned around and said,

Therell be a hot time

in the old town tonight.

Oh, Mister Johnny Verbeck,

how could you be so mean?

I told you youd be sorry

for inventin that machine.

Now all the neighbors cats and dogs

will nevermore be seen.

Theyll all be ground to sausages

in Johnny Verbecks machine.

Go tell Aunt Rhody

that the old gray goose is dead.

For me, those songs simply were. They entered my ears and joined the earliest of my memories, becoming as second nature as language.

As I grew, I wondered where they had come from. I think I realized, even then, that they hadnt materialized out of thin air; something between the lines told me they came from a place alien to me, recognizable to my father and even more familiar to the people who came before him.

In second-grade music class at Falk Elementary School in Pittsburgh, the teacher, Don Mushalko, taught us to sing about someplace called the Erie Canal:

We were forty miles from Albany

forget it I never shall.

What a terrible storm we had one night

on the Er-i-e Canal.

Only years later did I learn that my ancestors moved from upstate New York to Cleveland on the steamship Daniel Webster, which traversed the canal to Lake Erie. I thought of the song instantly: It was something real, a document of an experience that was about my country, my family, me.

As I prepared for college, my father insisted I couldnt leave the house unless I learned one of the two skills he felt were lifes most important: typing and playing the piano. As much as I loved listening to him play, I had no interest in doing it myself. I took a typing class in my junior year of high school and became a writer.

To type and to make music. Both are the same act, really. In each, it is not the action that matters but the echo it produces. I never learned the piano; finally, today, I am teaching myself. And I have come to realize that the music was always within me. My father got it from long ago, and he gave it to me. I just needed to awaken it.

After writing this book, which documents my determined search for the history of the song House of the Rising Sun and the paths it has taken through the world, I understand now: The secrets of the American tapestry can be unlocked with its music, if youre using the right batch of keys. And Key Number One is realizing how much of us can be contained in just one song.

Several years ago, when I wrote an article about the latest inductions at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, I referred to rock as mongrel music. Within hours, a reader dashed off an indignant email. I dont appreciate your terminology, he snapped.