S ETTING THE N ET

M EAN HIGH WATER: n. Average height of water at high tide.

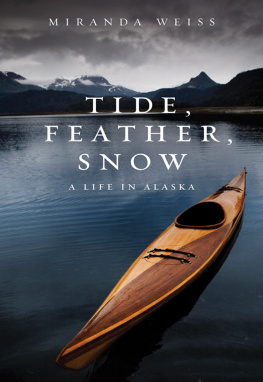

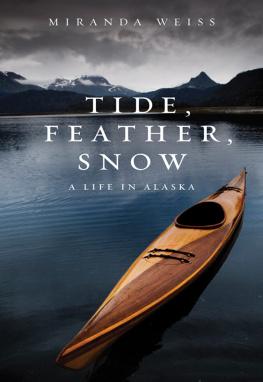

M oving to coastal Alaska meant moving to the water life, although I hadnt known it until I arrived. Nothing is separate from the seanot the sky, not the land, not a single day, nor my mood. I wasnt used to this. I wasnt ready for it.

I T WAS THE middle of July when John dragged out a tangle of net hed salvaged from the beach months before. In winter, wind and surf reshuffled the beach, exposing hidden treasuresrusty bicycles, boat parts. He had wrestled the gill net from the sand and now wanted to set the net in front of the house for silver salmon that ran along the shore toward streams farther up the bay. I couldnt conceive how such a thing should be donewhere to set the net, how to check it, what to expect. But John had a way of finding free stuff and asking a few questions here and thereat a potluck dinner, at the gear shop, in the neighbors yardand then hed know how to do it.

Johns certainty intimidated me. So I washed dishes and watched him through the kitchen window as he spread the clump of net on the lawn and got to work meticulously unwinding, untying, and straightening the whole thing out. The net took a day to untangle and decipher. When it was done, the mesh stretched sixty feet across the grass and lay ten feet deep. The float line, a line of white floats across the top of the rectangular net, would hang the net from the waters surface and the weighted lead line at the bottom would sink to keep it open when submerged. I helped John fold up the net in the way hed learned from a friend: He took the lead line and I took the float line and we walked from one end to the other, bunching it up along the way.

At low tide the next morning, I followed John down the edge of the bluff in front of our house, lugging the hind end of the net over my shoulder. I liked to believe my lithe, curveless body, though small, was strong and capable of bearing up to whatever I wanted to do. But I slipped under the weight of the net in muddy spots the wild raspberry had left bare. The sky was a wide open blue and the white sides of gulls glinted far out on the bay. In front of us, the retreated tide exposed a mud mirror that reflected the mountains across the water. Clam holes and the coiled castings of marine worms pocked and pimpled the reflection. We werent the only ones who had decided to try for silver salmon. Two nets were set in front of houses farther up the bay, and with the tide out, their lines and pink buoys lay idle on the flats.

John had planned it all out. We staked one end of the net close to shore, stretched the mesh perpendicularly across the mudflats, and then anchored the other end into the mud. Then we dragged the lead line away from the float line, opening the mesh. It was as flaccid as an empty sleeve and so far from the water it looked as though it would never be submerged. But John insisted that silver salmon run through the shallows. For good luck, we tied a buxom white mermaid buoy to the net. Then there was nothing left to do but wait out the tide.

E ARLIER THAT MONTH, we had bought fishing licenses at the grocery store and picked up a colorful newsprint booklet that explained the fishing regulations for Southcentral Alaska. The sixty-page publication included colorful drawings of rockfish and salmon, maps of river mouths and bays, instructions on how to efficiently kill your catch, and detailed directions on where and how to fish. John and I had moved to Alaska not quite a year earlier and had learned that with fishing, as with everything else, there were clear distinctions between locals and outsiders: Only residents could use nets to catch fish for themselves, while tourists were limited to hook and line.

New to the town of Homer and eager to fit in and stake out our own territory, we quickly realized that Kachemak Bay, on which we now lived, was already a crowded place. Even with its convoluted coastline and dozen islands, every bit of natures real estate had been claimed. All five species of Pacific salmon populated the bay, fattening off its rich waters and swarming local streams. Humpbacks, orcas, and fin whales regularly plowed the water, sending the sound of their exhalations over the surface of the bay. Forests of ribbonlike kelp grew thickly from the seafloor, feeding urchin and harboring sea otters, who napped while wrapped in the green fronds. Long strands of kelp washed ashore and quickly became whips and jump ropes for children playing on the beach, or were sliced and pickled in jars. When the bay withdrew at low tide in the spring, shorebirds up from California and Mexico on their way to nesting grounds farther north crammed the flats, needling their bills into the mud for pink, thumbnail-sized macoma clams. Above, marsh hawks patrolled for the stragglers and the weak. Hundreds of snow geese owned the head of the bay each spring, and the rocky shore on the south side of the bay, which was dimpled and nicked endlessly, was as populated and compartmentalized as the oldest city block. Sea lions claimed Sixty Foot Rock as their haul-out spot and occasionally lorded over the harbor, eyeing passersby with dogs. In summer, a clump of nearly naked rocks became a boisterous colony of nesting gulls, kittiwakes, puffins, murres, and cormorants. The chatter clattered loudly above the sound of the surf, and the ammonia smell of guano could burn your nose from more than a quarter mile away.

The town we had moved to called itself the halibut fishing capital of the world, and all summer long, charter boats ferried tourists to the mouth of the bay so they could drop lines to the bottom of the sea in search of these flat bottom fish. From time to time, a hook brought up a monstrously large halibut, which might bring its captor the annual derby loot, a prize large enough to buy a new luxury car unfit for local roads. These barn-door halibut are taller than a man, weigh more than three hundred pounds, and have to be shot dead before they are hauled onboard lest the flex of their tails swipe someone off the deck.

The commercial fishing fleet streamed out of the harbor starting in the spring. Seiners nosed into narrow fjords on the south side of the bay when salmon ran thick and followed fish up the inlet to net the oily-fleshed red salmon that pulsed by the millions into glacial rivers that emptied there. Crabbing boats docked until fall, when their harvesting frenzy would begin in the icy Bering Sea. Long-liners, gillnetters, and tenders brought fish-filled hulls back to the harbor to be unloaded by cranes. A long pipe that pumped waste from fish processing and packing plants back into the bay attracted a storm of gulls at its mouth. The commercial vessels, which docked closest to the entrance of the harbor, were being pushed aside by an expanding army of charter boats and water taxis, pleasure skiffs, and private yachts.

T HE CENTER OF town squatted between the end of the highway and the beginning of the shore, and I quickly realized the sea was the backdrop for everything that happened herea witness to weddings and deaths, to visiting dignitaries as well as to small, daily indignities. It hosted a beach barbecue for a visiting Kennedy and embraced a truck, stolen from a gay high school teacher, that had been charred and abandoned at the edge of the surf. Every house in town faced the bay or wished it did. And in places where there were no views of the sea, they had been painted on earnestly in colorful muralsinside the bank, on the side of the middle school, on a concrete wall next to the Christian bookstore, on the exterior of a shop that sold electronics for boats.