Published by

Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

202 Warren Street

Hudson, New York 12534

www.papress.com 2020 Kimberly Elam

All rights reserved.

23 22 21 20 4 3 2 1 First edition ISBN 978-1-61689-921-9 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-61689-973-8 (epub, mobi) No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews. Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions. Editor: Linda Lee

Designer: Kimberly Elam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Three-Dimensional Design

Principles, Processes, and Projects The digital world tends to physically separate the artist and designer from their work with a glass screen. The only tactile sensations are the controlled tap on the keyboard, scroll and click of the mouse, or the stylus sliding across a smooth glass surface, resulting in the brain almost exclusively processing visual stimuli.

The touch-driven three-dimensional world is far different. Tactile sensations ignite the brain, with about half of the brains processing power devoted to touch. Within this process the hands are the workhorses of the sense of touch and are the most highly developed tactile receptors in the body, and when coupled with visual stimuli, energize the brain to become a creative neural powerhouse. Imagine for a moment a sterile kindergarten classroom consisting only of blank walls and bland tables and chairs. This has to be imagined because all kindergarten classrooms are filled with colorful walls and arrays of paints, clay, crayons, blocks, and objects for children to touch. Everyone knows and teachers fully understand that engaging the sense of touch enhances and stimulates learning.

When learning involves touch, it transforms the experience by deeply engaging the brain in a way that promotes the development of knowledge. This is a substantial cognitive link that goes far beyond rote recall or memorization. The link between tactile sensation and learning does not diminish with age, and both adults and children benefit greatly from tactile learning. This is especially true of college art and design students, whose professions demand creativity. Tactile sensations not only stimulate the brains processing power, they also enhance the creative thought, idea, or concept. Our brains are wired to work this way, and it is a primal impulse to doodle or craft or twist a paper clip.

My art and design college, Ringling College of Art and Design, is known not only for its excellence in art and design education but also as one of the most wired campuses in the world. (This is a good thing.) And at the same time, some of the most popular courses on campus involve touch-driven handcraft, including glassblowing, letterpress printing, sculpture, woodworking, book arts, printmaking, and serigraphy. Students intuitively crave tactile experiences not only as a welcome release from digital practice but also to get their creative juices flowing and enhance their problem-solving skills. Introduction to Three-Dimensional Design collects a series of educational experiments that were conducted in my courses at the Ringling College of Art and Design. Almost all of the examples shown were designed, developed, and produced by freshmen design students in introductory three-dimensional design courses. These educational experiments are designed to tap into the benefits of tactile stimulation, and the students became my collaborators in testing ideas and developing the methodology.

The approaches to the elements and principles of design are carefully crafted to focus on key concepts, from the initial sketches and experimental prototypes through to the final model solution. The dynamic forces of three-dimensional contrast are explored in the Mask project, with contrast employed as a means of intensifying communication of the contrast through juxtaposition. In Wire Icons, the continuous graphic line is transformed from two to three dimensions as the line becomes a wire that is sculpted to capture volume and space. Graphic communication and three-dimensional communication come together through abstraction in Paper Food, which enhances geometric box shapes with color and abstracted patterns to create iconic fruits, vegetables, and sandwiches. The Acrylic Bird project stimulates the imagination and challenges the student to reduce the ellipsoid body of a bird into a cohesive and recognizable series of clear planes.  Radial Balance Bella Cicci

Radial Balance Bella Cicci  Rhythm Nicole Lavala

Rhythm Nicole Lavala  Harmony Darien Kupec

Harmony Darien Kupec  Emphasis Marcus Adkins

Emphasis Marcus Adkins

Chapter 1.

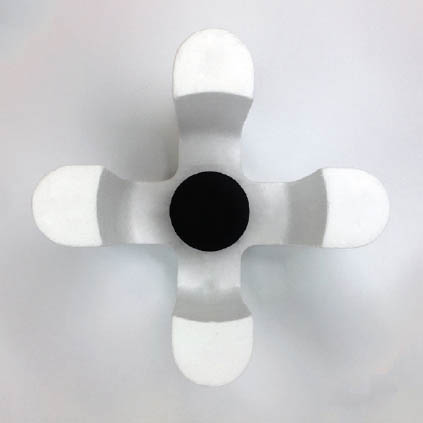

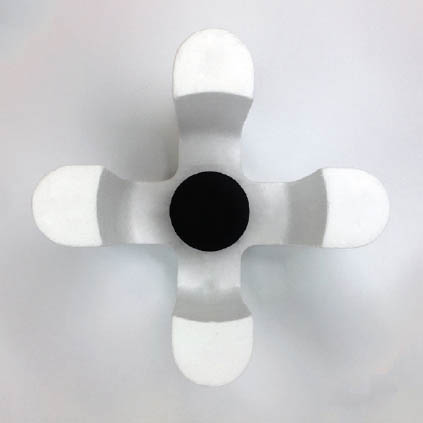

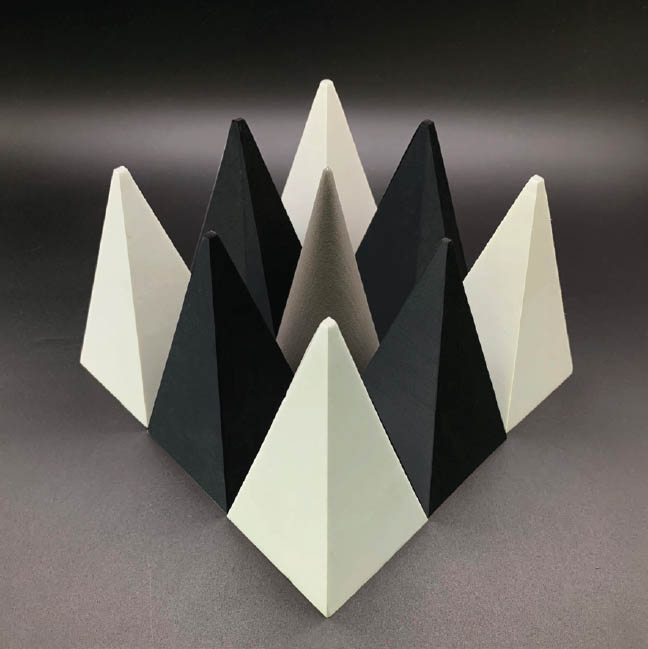

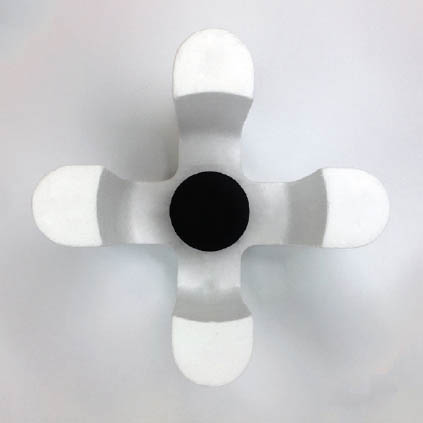

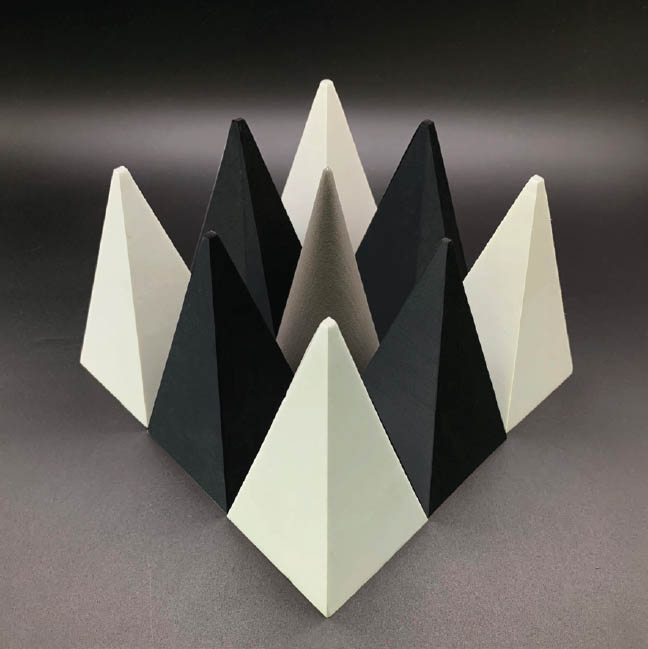

Radial Balance

Radial Balance Bella Cicci

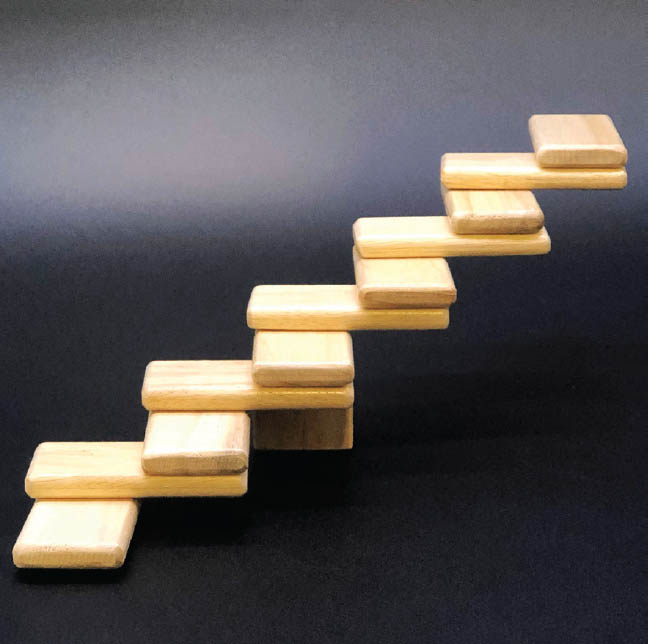

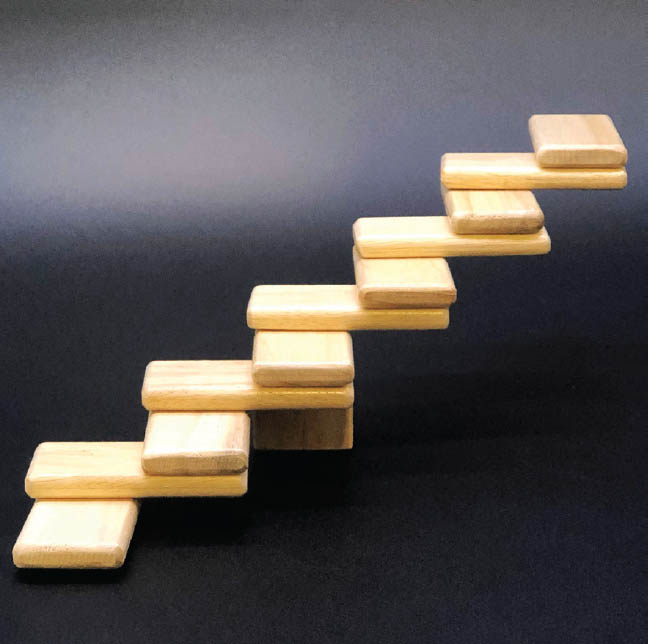

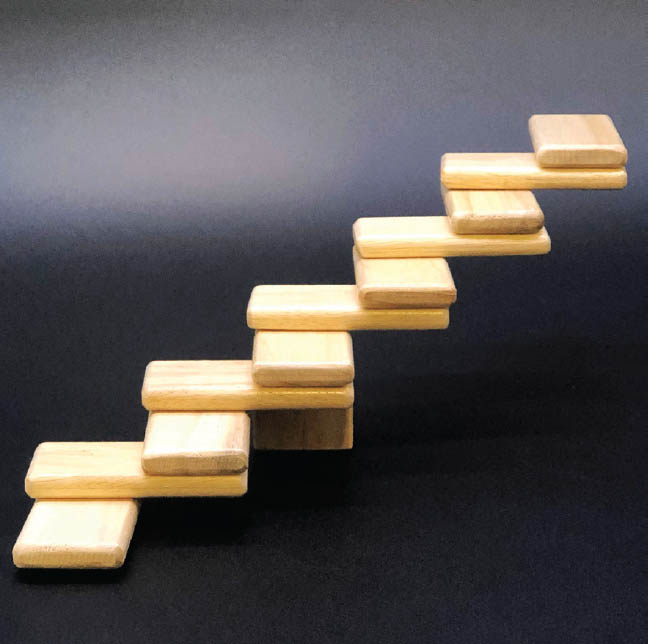

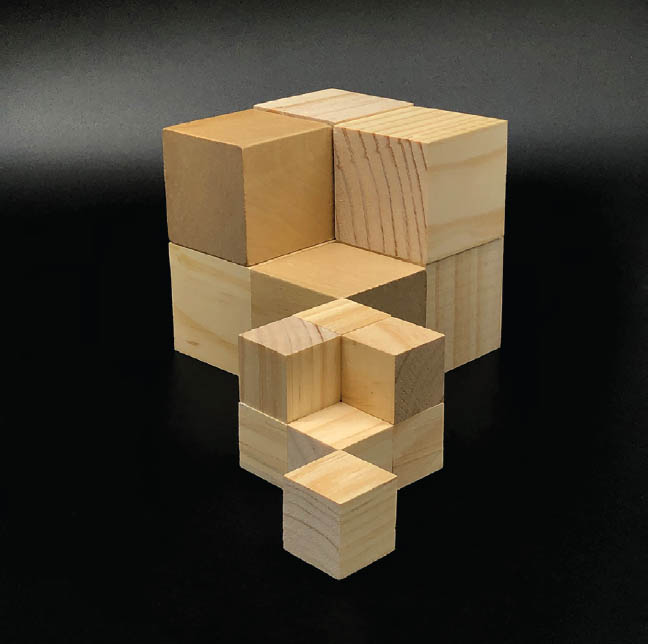

Rhythm

Rhythm Nicole Lavala

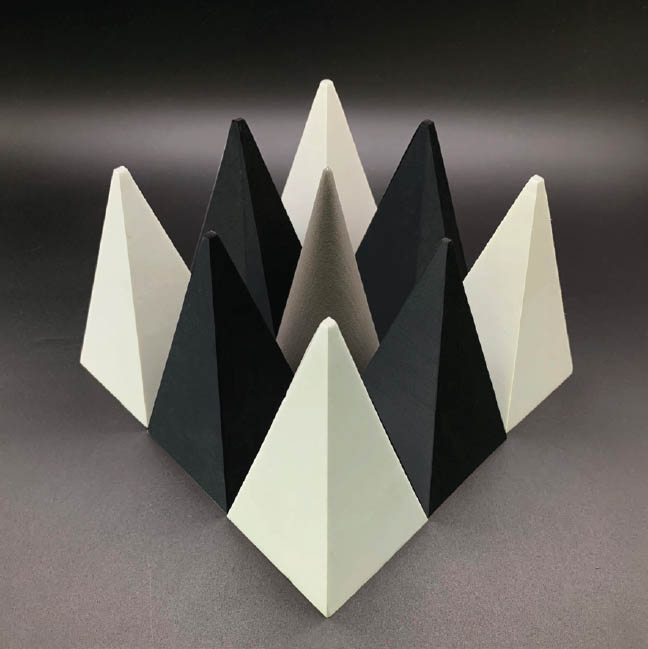

Harmony

Harmony Darien Kupec

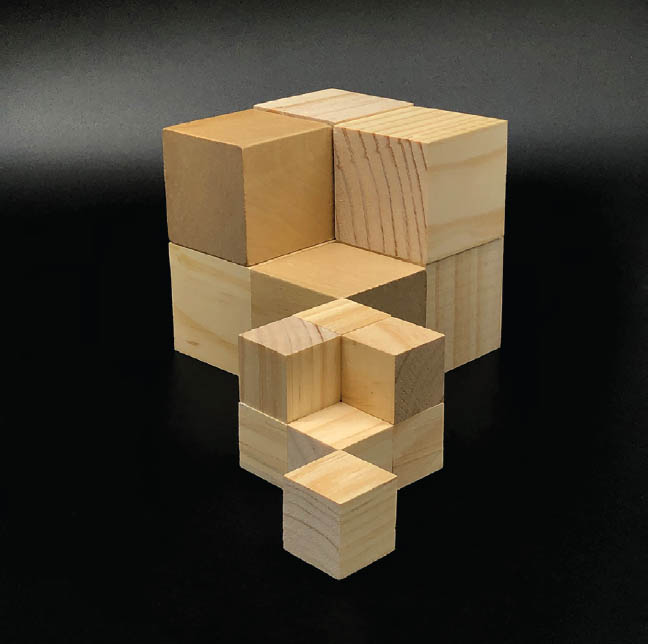

Emphasis

Emphasis Marcus Adkins

Chapter 1.

Principles of Three-Dimensional Design

The principles of three-dimensional design bring the elements of a design together. These principles are key concepts that describe methods of organizing, arranging, or juxtaposing three-dimensional elements with each other and to the composition as a whole. They are crucial visual forces that control the way the viewer interprets three-dimensional form.

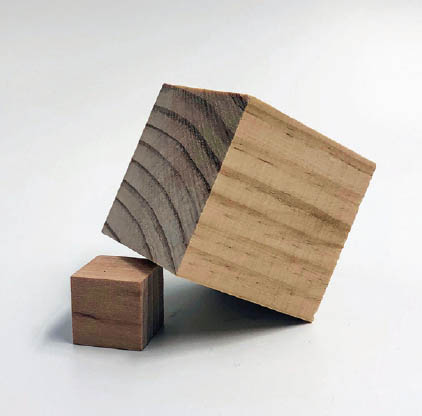

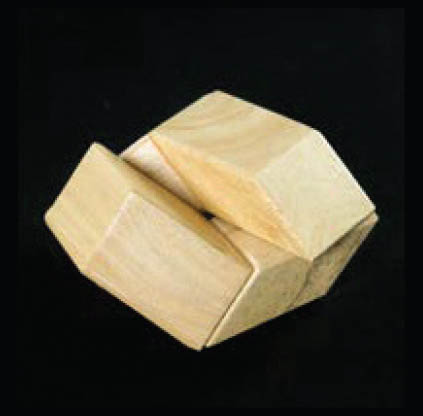

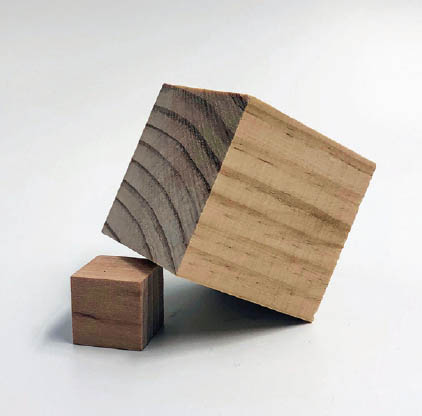

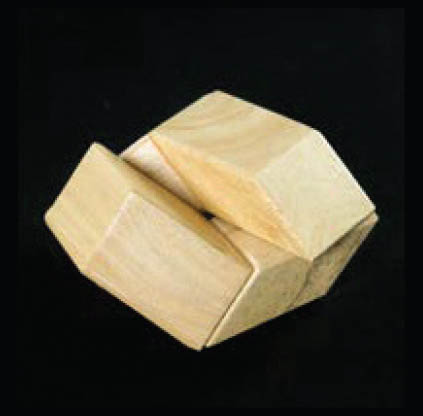

Proportion

Proportion Joel Reyes There are many points of view as to what constitutes a definitive list of the principles of design. The principles that have been chosen for this project are those that are common and often the most visually powerful in three-dimensional design. These include proportion, scale, symmetric balance, asymmetric balance, radial balance, rhythm, emphasis, and harmony.

These principles are readily understood in theory; however, in practice they become more complex as visual forces combine and overlap. The most important goal of the project is clear communication of the principle.

Published by

Published by Radial Balance Bella Cicci

Radial Balance Bella Cicci  Rhythm Nicole Lavala

Rhythm Nicole Lavala  Harmony Darien Kupec

Harmony Darien Kupec  Emphasis Marcus Adkins

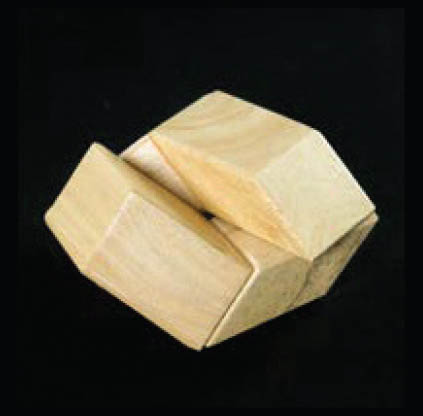

Emphasis Marcus Adkins Proportion Joel Reyes There are many points of view as to what constitutes a definitive list of the principles of design. The principles that have been chosen for this project are those that are common and often the most visually powerful in three-dimensional design. These include proportion, scale, symmetric balance, asymmetric balance, radial balance, rhythm, emphasis, and harmony.

Proportion Joel Reyes There are many points of view as to what constitutes a definitive list of the principles of design. The principles that have been chosen for this project are those that are common and often the most visually powerful in three-dimensional design. These include proportion, scale, symmetric balance, asymmetric balance, radial balance, rhythm, emphasis, and harmony.