IMAGES

of America

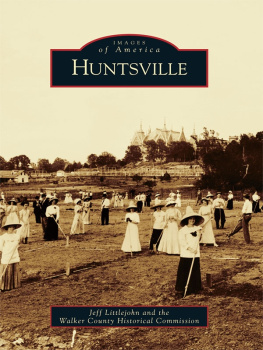

HUNTSVILLE

PENITENTIARY

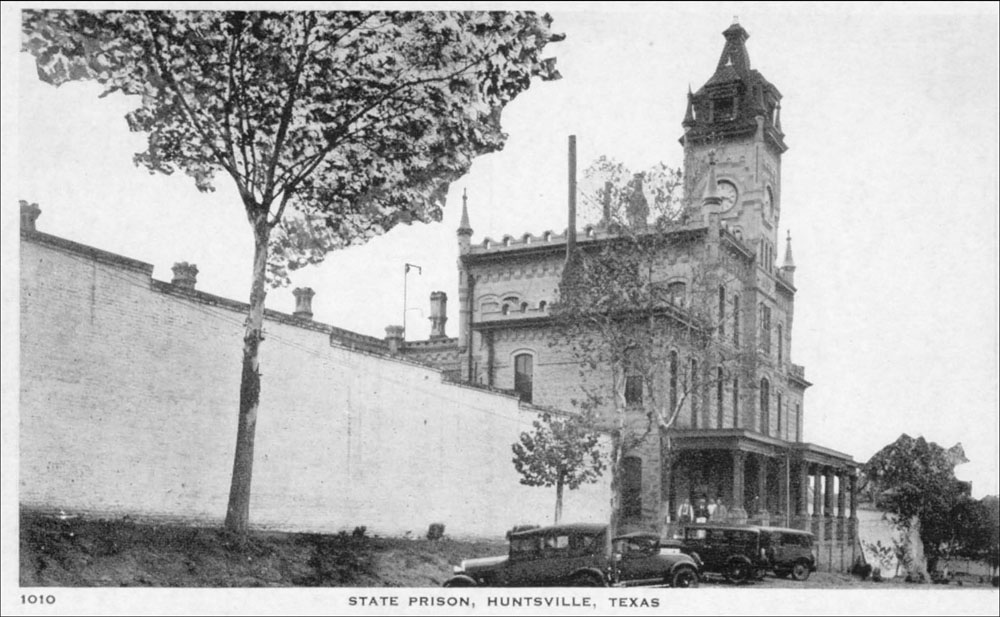

This postcard view of the administration building of the Huntsville Penitentiary was taken from the southwest corner in the late 1920s. Note the clock tower and the brick wall. Prison employees can be seen standing on the front porch. This structure was replaced with a new administration building that opened in 1942. (Courtesy of the Texas Prison Museum.)

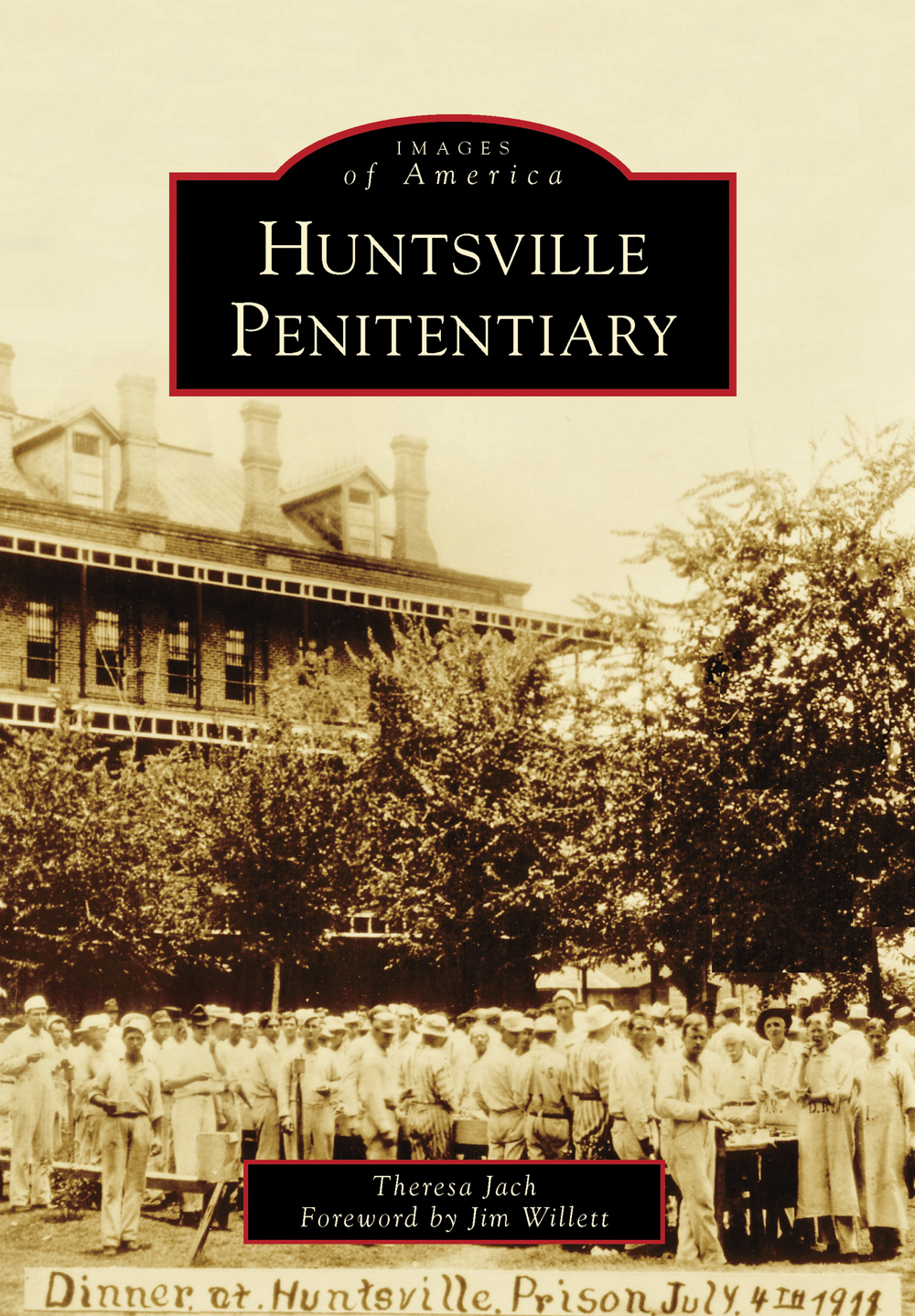

ON THE COVER: Inmates are pictured at a 1911 Fourth of July gathering in the courtyard of the Huntsville Penitentiary, with the prison hospital in the background. Following a legislative investigation into abuses throughout the prison system, a prison reform law had gone into effect in January 1911. A new system of registering convicts had been implemented, requiring that all incoming inmates be photographed. The white uniforms shown on the convicts were also a new addition, replacing striped uniforms (the stripes would continue to be used for incorrigible inmates). Huntsville was increasingly reserved for white convicts, with African Americans being sent to prison farms. The recently reelected governor of Texas, Oscar Colquitt, who had campaigned with promises to improve prisons and ban the use of the whip as punishment, visited the Huntsville Penitentiary for the Fourth of July picnic. (Courtesy of the Texas Prison Museum.)

IMAGES

of America

HUNTSVILLE

PENITENTIARY

Theresa Jach

Foreword by Jim Willett

Copyright 2013 by Theresa Jach

ISBN 978-0-7385-9961-8

Ebook ISBN 9781439643570

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012956012

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

This volume is dedicated to the wonderful people at the Texas Prison Museum who have made it their mission to preserve the important history of the Texas prison system.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

The importance of the state prison system to Huntsville, Texas, cannot be overemphasized. It is hard to imagine what our town would be like without the prisons, the jobs they afford, and their assistance to our community and the overall welfare of our town. Having the headquarters for a state agencythe Department of Criminal Justicelocated here in addition to the five prisons inside our city limits is a huge boost to our economy. The general public can learn a lot about their prison system by visiting the Texas Prison Museum, rightly located in Huntsville, Texas.

James Willett

Director of the Texas Prison Museum

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Unless otherwise noted, the images in this volume are from the collection of the Texas Prison Museum. Former employees and their families have donated photographs to the museums archive, providing an important resource for historians and history buffs alike. Other images were provided by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (via the Texas Prison Museum), the Texas State Libraries and Archives, and the Thomason Room archive at Sam Houston State University.

Special thanks go to Jim Willett, the director of the Texas Prison Museum, and Sandy Rogers, the museums registrar and archivist. They provided invaluable access to photographs in their collection and willingly shared their vast knowledge about the prison. Sandy graciously met me on her day off and even gave me a tour of Huntsville. I would also like to thank my husband, Tim, for listening to all of my prison stories, and my colleagues at Houston Community College-Northwest for their interest in this project.

INTRODUCTION

The State of Texas opened its first prison in 1849 in Huntsville, located in Walker County, about 70 miles north of Houston. A three-member board appointed by Gov. George Wood chose this location. When built, this new penitentiary was to serve as an alternative to more barbaric practices of capital and corporal punishment for crimes. Penitentiary advocates hoped these facilities would rehabilitate offenders, making them productive members of society, while at the same time protecting citizens from danger. This first step foreshadowed the development of one of the largest prison systems in the world. Construction on the first building began on August 15, 1848, under the supervision of architect Abner Hugh Cook. While the main cell block was being built, a temporary wooden jail was constructed on the property to house the first convicts. Once the main building was complete, Cook was to utilize convict labor to complete the prison and the surrounding wall required by the legislature. The legislature also mandated the inclusion of a sturdy surrounding wall to enclose the prison building and grounds. The prison would soon earn the nickname the Walls for the brick structure enclosing the cell blocks and courtyard. The first prisoner, convicted cattle thief William Sansom of Fayette County, arrived in October 1849. By January 1850, there were three inmates at the Huntsville Prison. The second to arrive, convicted murderer Stephen Terry of Jefferson County, has the dubious distinction of being the first inmate shot and killed by guards while trying to escape; he had been in Huntsville for less than a year. The first female inmate, Elizabeth Huffman, served a one-year sentence, beginning in 1854, for killing her newborn infant.

The number of inmates remained small before the Civil War, when only white men were routinely subject to punishment by the state. For example, in January 1855 there were 75 inmates at the prison. Although there were relatively few inmates, Texas politicians were determined to create a self-sustaining prison that would not burden taxpayers. In 1853, Gov. Peter Bell requested a $35,000 appropriation to build a textile mill at the facility. Producing cotton and wool cloth, the prison earned a profit selling rough material for slave clothing. During the Civil War, the prison textile mill also generated a significant profit with the production of cloth for Confederate uniforms. Following the war, the inmate population in Texas grew dramatically, altering the system and leading to new efforts to find more income from convicts. While Huntsville continued to operate various moneymaking enterprises, the bulk of the prison systems income came in the form of convict leasing. This system, which was in place until 1914, saw thousands of prisoners leased to privately owned cotton and sugar plantations. The majority of leased convicts were African American. Some white convicts were leased to railroad companies. As the state moved away from the brutal lease system, they began purchasing farms on which to put convicts to work. These farms served as the basis for a prison system that spread across that state and now encompasses nearly 50 prison units (not including various facilities operated by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, such as transfer facilities, psychiatric facilities, or prerelease facilities). Huntsville remains as the hub of the system today. Ephram Stephenson designed the current incarnation of the prison. Work on remodeling much of the prison began in 1934, and Stephenson oversaw the building of an arena for the prison rodeo and the redbrick wall that surrounds the facility today (the old sandstone brick wall was covered over with a redbrick facade). He also designed the new redbrick administration building.

Next page