Praise for

ROWING THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE

Climate change is happening so rapidly in the Arctic that it is absolutely essential that people go there and intelligently record what they see, as Kevin Vallely so compellingly does in Rowing the Northwest Passage.

PETER WADHAMS, author of A Farewell to Ice

A thrilling adventure tale in which each hard mile not only reveals the strength of the human spirit but also hammers home the hard truths of climate change.

CAMERON DUECK, author of The New Northwest Passage

A compelling page-turner of an adventure story.

ROZ SAVAGE, Guinness World Record-setting ocean rower

Vallely transports the reader to places few will ever go: the very edges of the earth and of human endurance.

EVAN SOLOMON, host of CTVs Question Period

A must-read for any Arctic or Northwest Passage enthusiast or for anyone concerned about our planets future in the face of global warming.

CAPTAIN KENNETH K. BURTON, Executive Director, Vancouver Maritime Museum

Combines a fantastic tale of adventure with an important message on the state of our environment. Vallelys writing keeps the reader engaged with beautiful descriptions of the people, landscapes and wildlife he encounters.

COLIN ANGUS, author & National Geographic Adventurer of the Year

What this modern saga of the Northwest Passage brings to light is the new image of the passage as canary in the coal mine. A warning sign of vast planetary changescaused by us and threatening our future.

ELIZABETH MAY, leader of the Green Party of Canada and MP for SaanichGulf Islands

A powerful call to action wrapped in a rich tale of adventure, history and the harsh reality of a changing climate.

ERIC SOLOMON, Director, Arctic Connections at the Vancouver Aquarium

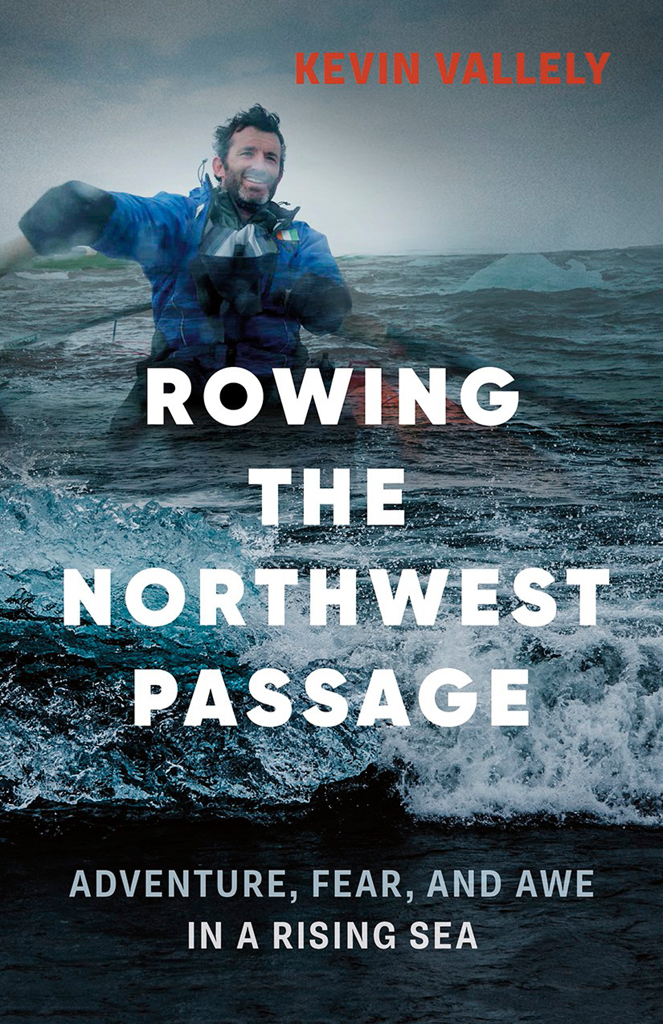

KEVIN VALLELY

ROWING THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE

ADVENTURE, FEAR, AND AWE IN A RISING SEA

Vancouver/Berkeley

To my Dad whose spirit is with me always and to my Mom whose unwavering support has never faltered.

Copyright 2017 by Kevin Vallely

17 18 19 20 21 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Greystone Books Ltd.

www.greystonebooks.com

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-77164-134-0 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-77164-135-7 (epub)

Editing by Lynne Melcombe

Copy editing by Stephanie Fysh

Cover and text design by Naomi MacDougall

Cover photograph by Kevin Vallely

Photographs by Denis Barnett,

Kevin Vallely, and Frank Wolf

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada for our publishing activities.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I SOWED THE FIRST SEEDS of an idea to traverse the Northwest Passage two decades ago during a conversation with friend and world-class adventurer Jerome Truran. It was a casual chat about what adventuring world firsts remained to be done. We agreed that traversing the Northwest Passage under human power in a single season was at the top of the list. But at the time, it was impossible. The Northwest Passage didnt open up for long enough during the summer months to contemplate such a feat. Our idea remained just that.

I was an active outdoor athlete taking part in an array of adventure sports, from rock climbing to kayaking, backcountry skiing to trail running, but I had never undertaken an expedition. I was enamored of the idea of striking out and doing something unique, testing my limits in the spirit of true adventure. I had no idea those early yearnings would chart a life course that would steer me toward a career in exploration.

The Arctic has interested me since I was a child. My father operated a radio at the Hopedale Mid-Canada Line station on the northern Labrador coast in the early 1960s, and his stories of his time there fascinated me. He was a new immigrant to Canada from Limerick, Ireland, and this was his first job in his new country. Isolated and remote, Hopedale was one of a series of radar stations that ran across the middle of Canada to provide early warning of a Soviet bombing attack on North America. For a young man more accustomed to the temperate climate of southern Ireland, this wild new land couldnt have come as more of a shock. He told me of endless winter darkness and cold so intense, human skin would freeze in seconds. But he also talked of the ephemeral play of the aurora borealis as it danced across the inky night sky and of an exquisite silence broken only by the beating of his own heart. It was a world both terrifying and raw that could still seduce through wonder and surprise.

My father was one of only three working at Hopedale. One winter night just after a temporary construction crew had flown out from the facility, a fire broke out and the radar station burned to the ground. My father and the two other operators barely escaped with their lives and had to survive in a storage shed until rescuers could fly in. This, to me, was the epitome of excitement and adventure. Ive seen the Arctic as a romantic landscape for as long as I can remember.

My first major expedition was in February 2000, when I skied the length of Alaskas 1,000-mile Iditarod Trail from Anchorage to Nome with two teammates. The journey opened my eyes to real adventure and I never looked back. In the coming years, I climbed active volcanoes in Java, Indonesia, in the midst of jihad, repeated a 1,250-mile Klondike-era ice-bike journey through the dead of an Alaskan winter, and became the first person since World War II to retrace the infamous Sandakan Death March through the jungles of Borneo.

A key adventure for me took place in 2007, when I traveled to the Canadian High Arctic to explore the beaches of King William Island, searching for clues from the doomed Franklin expedition. With the help of Inuit historian Louie Kamookak, I saw skeletal remains, likely from the Franklin crew, that were still scattered about the land and yet remained uninvestigated and untested. Evan Solomon, an anchorman for CBC Sunday-night news at the time and my teammate on the expedition, made a compelling documentary of our journey and discussed the political indifference being shown to a pivotal historical event in Canadian history. That was when I realized that an expedition could be more than a personal test of stamina; it could also be a vehicle for sharing an important message.

An adventure in 2009 drove that point home. That year, Ray Zahab, Richard Weber, and I broke the world record for the fastest unsupported trek from the edge of the Antarctic continent to the geographic South Pole. Throughout our journey, we maintained real-time communication with over 10,000 schoolchildren around the world. By the end of the journey, wed garnered a staggering 1.5 billion media impressions. For me, this demonstrated the formidable reach a well-publicized expedition can garner when theres a worthwhile message to share.