For Veena,

and in memory of Albert, who first led the way.

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

This electronic edition published in 2016 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Absolute Press, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Absolute Press

Scarborough House

29 James Street West

Bath BA1 2BT

Phone 44 (0) 1225 316013

Fax 44 (0) 1225 445836

E-mail

Website www.absolutepress.co.uk

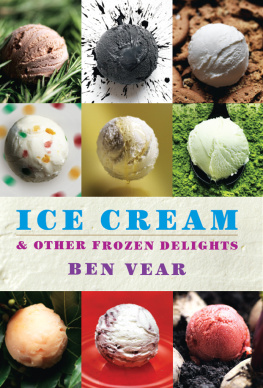

Text copyright

Ben Vear, 2013

Photography copyright

Mike Cooper,

except Jessica Beveridge

Publisher

Jon Croft

Commissioning Editor

Meg Avent

Art Director

Matt Inwood

Project Editor

Alice Gibbs

Editor

Eleanor van Zandt

Photographer

Mike Cooper

Food Stylist

Genevieve Taylor

Indexer

Ruth Ellis

The rights of Ben Vear to be identified as the author of this work have been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-9066-5085-8

ePub 978-1-4729-3318-8

A note about the text

This book was set using Century. The first Century typeface was cut in 1894. In 1975 an updated family of Century typefaces was designed by Tony Stan for ITC.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

Like most people, I fell in love with ice cream as a child...

I well remember joyfully running out into the road on Sunday afternoons to meet the ice cream man. However, in my case the ice cream man was a member of my family sometimes my uncle, or my dad or, usually, my granddad.

My clan, the Winstones, have been making ice cream in the Cotswolds since 1925. Our factory, near Stroud, supplies luxury ice cream to food retailers throughout the land, and many people flock to our own little shop to buy it directly from us. Its always gratifying to see how excited people can get as they tuck into a scoop or two of our Rum & Raisin, for example, or Butterscotch Chip.

Gratifying, but not really surprising. At its best, ice cream offers a delicious, multi-sensory experience, appealing to more than just our taste buds. Its smooth, melting texture also tantalises our sense of touch; its delicate fragrance, derived from any of innumerable different flavours, charms our sense of smell; and its beautiful colours and glistening surface entice our eyes.

When, in the past, ice cream was still a rare luxury, difficult to produce and enjoyed only by the rich, it was held in high regard. An aura of mystery hung around this seemingly magical confection. At the very least it was considered one of lifes great sensual pleasures. The eighteenth-century French wit Voltaire once observed, Ice cream is exquisite; what a pity it isnt illegal implying that this would make it even more seductive.

Well, all that has changed. Today supermarket cold cabinets are filled mainly with imitation ice cream produced using a cocktail of different chemical emulsifiers, preservatives, artificial flavourings and enhancers. Much of this air-filled pap has never come close to a cow. Clearly, when it comes to ice cream (and many other foods as well) we have lost our way.

Fortunately, quality ice cream is now making a comeback. Various new artisan ice cream producers have started up in recent years, and my own company is flourishing and growing. But, depending on where you live, if you want to buy really good ice cream in a wide range of flavours, you may need to seek it out and, admittedly, spend a bit more money.

Thats where this book comes in. The following pages contain one hundred of my recipes for ice creams, sorbets and other frozen treats which you can easily make, at relatively little expense, in your own kitchen. All you need is some good ingredients, basic kitchen equipment (an ice cream maker, though useful, is not essential) and a little patience. Once youve understood and practised the basic techniques , you can use these to create your own variations and original, unique flavours.

I hope this book will help you to discover or rediscover the pure pleasure of eating truly delicious ice cream.

For thousands of years people have enjoyed eating something cold and sweet...

The ancient Romans are known to have stored ice from the mountains in vast ice houses and sweetened it with honey and fruit, making something similar to what we know today as a granita. The Persians had their own form of water ice, made with snow. However, the first appearance of something resembling ice cream seems to have been in China, during the Tang dynasty (618907), when emperors and their courtiers ate concoctions made of milk from cows, goats and even buffaloes, frozen and sweetened with sugar, herbs and spices. Somewhere along the way, again probably in China, it was discovered that adding salt to ice caused it to melt more quickly, at the same time causing the creamy mixture contained inside it, when repeatedly stirred, to freeze into a smooth, semi-solid consistency.

According to legend, it was the Venetian explorer Marco Polo who, in the thirteenth century, brought the secret of making ice cream from the Far East back to Europe. Whether or not this is true, it does seem to have been the Italians who launched iced cream in the West, as well as water ices, flavoured with fruit and, often, spirits. Labour-intensive and costly, ice cream was for many years enjoyed only by the top people. It reached the French court sometime in the seventeenth century and soon spread to other royal tables. One observer, reporting on a banquet for King Charles II at Windsor Castle in 1671, remarked that guests at the Kings own table (only) were presented with One Plate of Ice Cream.

By the early eighteenth century, the secret of making ice cream was beginning to circulate more widely. A French pamphlet entitled LArt de faire des Glaces (The Art of Making Ice Cream) appeared around 1700. Published in England in 1718, Mrs Mary Eales Receipts included some recipes for ice cream. Such publications were eagerly snapped up by affluent gourmets who wished to impress their friends.

Next page