Contents

For Steve

As I write this, back in the real world, back in an office, back home, back up against a deadline, I glance down at the mousepad to my right, and I am filled once again with powerful longing. The pad is printed with a picture of a laughing woman stripping off a wetsuit on a golden beach. Her hair is streaked blond, her shoulders broad on an otherwise slender frame, muscular shoulders that look like they know how to work. She is completely relaxed, and radiates happiness. The slice of beach in the photo is desertedpristine, private, no one and nothing on it, except for a pile of snorkeling gear in the sand at the womans feet. Behind her, the sea is turquoise glass, on which sits a lone boat with a white hull and a tall mast that has impaled the skys single puffy white cloud like cotton candy on a stick.

The woman does not appear to be looking at anyone, to even realize that her photo is being taken. She is just plain damn happy.

That woman is me.

Island Time

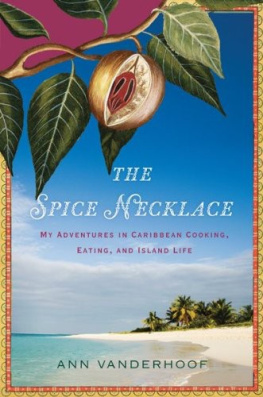

The market ladies sell spice necklacesgarlands of cloves, cinnamon bark, bay leaves, cocoa beans, mace, and nutmegthat are irresistible. I now have them hanging all around the boat, making it smell spicy and delicious. Mangoes are in season, and literally falling off the treesan embarrassment of mangoes, to someone from the north. We feel duty bound to try as many varieties as we can.

JOURNAL ENTRY, JULY 1998

In the distance, the hills on Hog Island are soft black silhouettes against a paler starlit sky the color of sharks skin. Fish skip across the ocean surface in front of our small inflatable dinghy, each one a quick metallic sparkle in the beam of my flashlight. The air is heavy, warm, scentedpartly a salty sea smell, from the shiny-wet rock wall close to us on one side, which has just been uncovered by the falling tide; but partly, too, the smell of lush land floating out from the dark hillsides, the fragrance of white frangipani and blooming spice trees.

Steve points our dinghy at the taller of the islands rounded hills, and from my perch in the bow, I begin a slow, measured count, just loud enough for him to hear over the burble of the outboard: Onnnnne Mississippi... twooooo Mississippi... threeeee Mississippi... When I reach tennnnnnn Mississippi, Steve pulls the tiller to turn us toward the second, smaller hill, farther to the north. Within seconds now, if Ive counted at the correct speed, my flashlight should pick up a pair of cantaloupe-sized white floats bobbing on the ocean ahead of us. About 20 feet apart, they mark a deep-water route that threads between patches of coral reef lying just below the surface. We had timed the turn during daylight, when the sea was serene and the sun high overhead, when we could clearly see the sapphire ribbon of safe water between the dappled yellow-green reefs.

Slow it down, slow it down, I dont see the floats yet, I call back to Steve, panning my light nervously in wide arcs. We have to spot the floats before proceeding. If we dont follow a line straight between them, we will almost certainly grind to a halt on the reef, damaging both it and our prop, and impaling the dinghy on the coral spikesa far-from-appealing idea in a small rubber boat, in the darkness, on the ocean. He cuts the throttle.

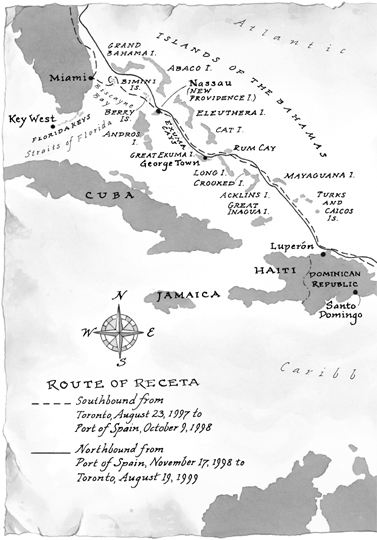

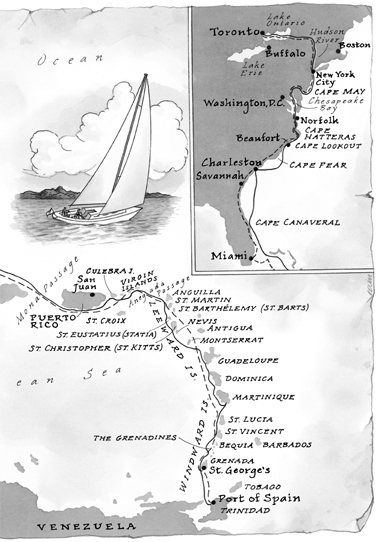

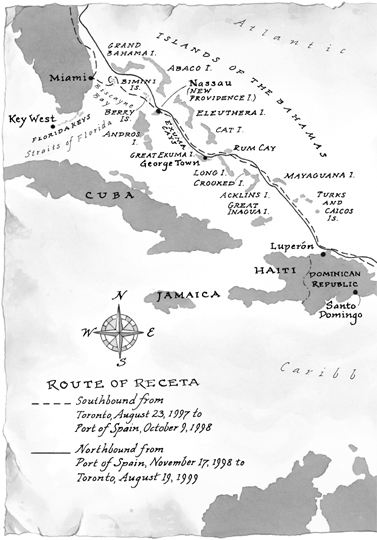

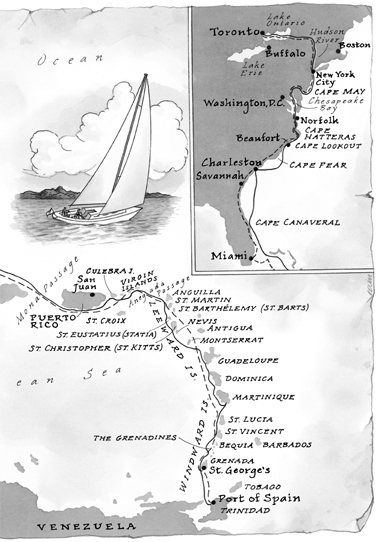

We are heading home from dinner out with friends on the night of my forty-sixth birthday, and this thread-the-needle-in-the-dark dinghy trip is what heading home now involves. Because home these days is a 42-foot sailboat named Receta, which currently floats off the southeastern coast of Grenada, in a protected bay behind these shallow reefs. She has carried us to the Caribbean from Toronto, where we lived and worked until a year ago, and where well return a year from now2,100 miles south as the crow flies, but much, much farther as the sailboat travels.

There. Got em. The white balls gleam as I flick my light from one to the other so Steve can see the gap. Were right on course. The anchorage opens up ahead, between a short finger of mainland Grenada on one side and a barely disconnected thumb of land, Hog Island, on the other. The masts of maybe twenty boats inscribe gentle arcs in the night sky, but I can pick Receta out from her neighbors by the T that glints near the top of her mast when I shine my light on it. I had placed that T there myself seven months earlier in Key Biscayne, Florida. Steve had winched me up the mast, and with both arms and both legs wrapped around it so tightly that the muscles ached for days afterward, I had peeled the backing off pieces of reflective tape and slapped them hurriedly on the metal, desperate to be lowered back down to sea level as quickly as possible. At the time, the reflective T was just an excuse to make the trip 50 feet above the waters surface; the real reason was to prove to myself I could do it if I had to. At the time, it was still hard to imagine we would actually ever use the T to help us find our way home at night.

As the dinghy putts closer, Steve kills the engine so we glide the last few feet to Receta. The slip-slap-slip-slap of our wake on the hull dies away, and quiet seems to resettle on the darkness. In fact, the night is incredibly noisybut the piping of thousands of tree frogs is by now an accustomed background sound, as ordinary and unremarkable a part of the summer night as the hum of an air conditioner once was. I grab the boats swim ladder, tie the dinghy to a cleat, and climb into the cockpit. Were home.

A bus comes hurtling around the curve past Nimrods rum shop every ten minutes or so, and while you wait you can watch Hugh Nimrod lettering a sign under the spreading ginnip tree next to the shop, his hands steady but his eyes a gentle haze of rum. If Hugh is inside serving a customer, there are always the goats to watch, the spindly young ones suckling on their mamas, who continue to graze intently up and down the roadside, pointedly ignoring the kids they drag along.

The morning is cool and green, the sun not yet risen high enough behind the mountains to feel its heat. Its market day for us, and we have zipped across the turquoise bay in the opposite direction from last night and tied our dinghy to the long skinny dock at Lower Woburna village of a hundred or so people, a handful of tiny stores, a few chickens and goats, and a riotous profusion of banana, mango, coconut, breadfruit, and papaya trees. The local fishermen and lobster divers dont bother with the dock; they just pull their heavy wooden boats up on the sliver of beach and run a line to a palm tree, leaving the dock free for kids to cannonball off the end or fish with their handlines, and for people like us to tether our dinghies when we come ashore.

A couple of minutes walk up the road from the dock brings us to Nimrods, where the bus stopsbut, then again, the bus will stop almost anywhere along the winding road if you wave, or point, or scratch your nose, or slow your pace even a fraction, suggesting you just

Next page