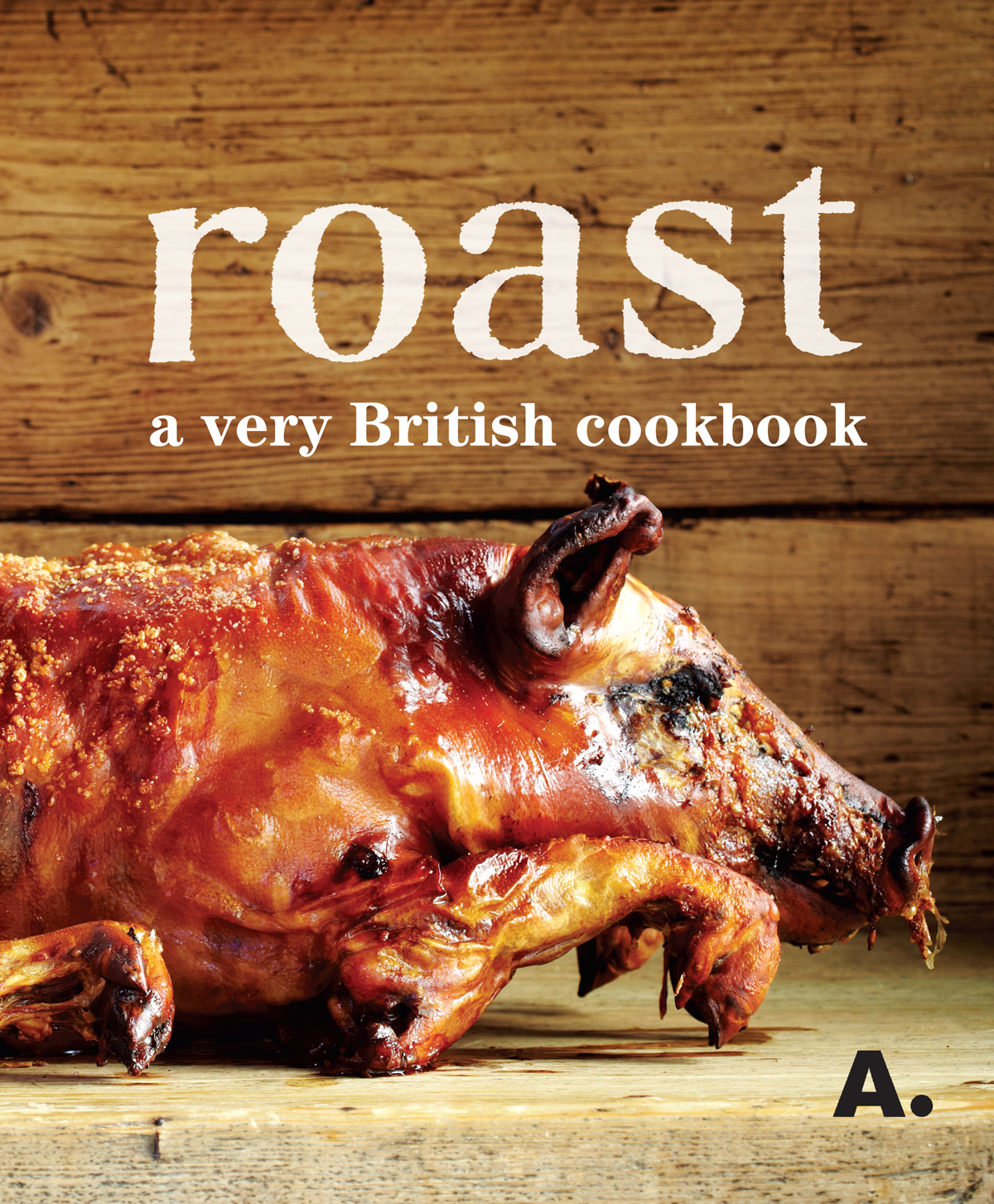

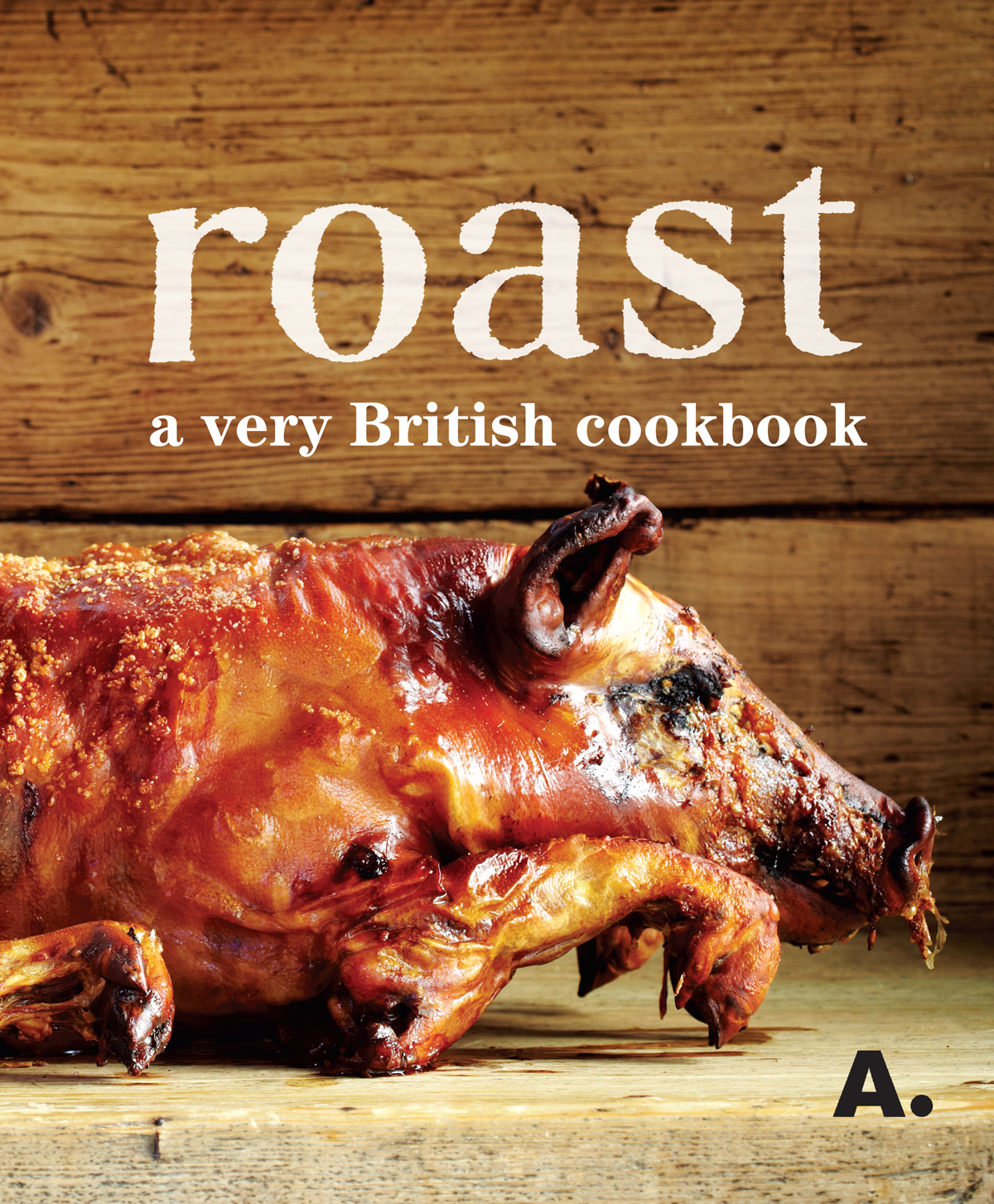

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Absolute Press, an imprint of

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

This electronic edition published 2016 by Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Absolute Press

Scarborough House

29 James Street West

Bath BA1 2BT

Phone 44 (0) 1225 316013

Fax 44 (0) 1225 445836

E-mail

Website www.absolutepress.co.uk

Text copyright

Roast Restaurant, 2013

Photography copyright

Lara Holmes, 2013, except inside cover,

Michael Potter and , courtesy

Roast Restaurant

Publisher

Jon Croft

Commissioning Editor

Meg Avent

Art Director

Matt Inwood

Project Editor

Alice Gibbs

Editor

Imogen Fortes

Photographer

Lara Holmes

Props Styling

Matt Inwood and Lara Holmes

Food Styling

Marcus Verberne

Indexer

Zoe Ross

The rights of Roast Restaurant to be identified as the author of this work have been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-4081-9346-4

ePub: 978-1-4729-3550-2

A note about the text

This book was set using Century. The first Century typeface was cut in 1894. In 1975 an updated family of Century typefaces was designed by Tony Stan for ITC.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

Introduction by Iqbal Wahhab OBE Founder, Roast

British food. Difficult, isnt it? When I was embarking upon Project Roast, I told one of my teenage nephews that I was going to create a British restaurant and he asked whether this would involve serving chicken tikka masala, my most detested dish. After all, whats more British than that?

It was 2003, where conventional wisdom would more naturally place me in The Cinnamon Club when I first started thinking what today sounds slightly absurd. That Britain needed a first-class British restaurant.

Let me give you a simple challenge: if you were in Paris, might you ask your hotel concierge to recommend a decent French restaurant in the city; or in New York, a good American place you might visit? Now imagine you are a visitor to London and you ask your concierge to get you a table in one of Londons best restaurants. On his Rolodex hell probably have: The Square (French), Zuma (Japanese), Hakkasan (Chinese) and Benares (Indian). He would get you into one of these and get himself a hefty tip when you returned. Yet a decade ago, he wouldnt have risked his reward by suggesting a British restaurant primarily on the grounds there were hardly any to speak of, let alone any worth recommending.

The rediscovery of our love of British food has many complex layers but let me explain my own journey into it. My family arrived in Britain in 1964 from what was then East Pakistan, now Bangladesh. I was an eight-month-old baby; my brother was five and my sister was seven. The rest of my family had only ever eaten Bengali food. As a child I didnt take to spice in the way my family had done (they had had no choice), so strange as it sounds, as a child growing up in south London I really looked forward to school dinners to as an alternative to what was served at home. Mum used to have to make separate meals for me but as she had a busy day job, this would involve compromises. While the rest of family ate rice and fish curry, I would have rice and fish fingers. There was a part of our freezer that was just for me Birds Eye beef burgers and chips being a staple. However, as Mums career took off (she was the first non-Christian head of a Church of England school), it was too much to expect her to make a separate meal for me, so at the age of 11 I made my first shepherds pie.

As a teenager often in trouble (I ran a small but profitable gang in south London), much of my time was spent away from home in caffs, pie and mash shops, then Wimpy outlets, and finally pubs. I suppose part of my rebellion towards my family involved rebellion to their food. This was the age of assimilation the precursor to integration and multi-culturalism. In those days social policy wonks decreed that what was for the best was for everyone to adopt British ways. My parents were encouraged only to speak English to me, whereas we now know that multilingual children fare much better. To this day my spoken Bengali is laughable and my read- and writeable Bengali non-existent. That remains a gap in my cultural identity not being entirely English and not being much cop as a Bangladeshi either. The overall umbrella of Britishness forgives a lot.

This desert which I inhabited had many unpredictable food consequences. At the age of 15 I became a curry convert and with all the zealotry that a convert is equipped with, every Saturday I would make a blisteringly hot mutton or oxtail curry for the family as a sort of penance for my weekday misdemeanours. A good curry forgives a lot too.

During the 1970s huge social changes were taking place, often driven by food. The advent of McDonalds, Kentucky Fried Chicken and the Chinese take-away, soon followed by the Indian and the pizza joints, meant that kids were eating away from home for the first time and in due course families that werent eating together werent staying together. In the context of the exotic allure of food from other countries, traditional British offerings represented the past bygone days, brilliantly captured by the satirical TV show Spitting Image with its image of dull Prime Minister John Major proving just how dull he was by portraying him in grey, eating grey chips and peas. That pretty much was a kiss of death for British food for quite a while.

Lets fast-forward to 1994: my food PR company and one my clients, Cobra beer, launched the first ever trade magazine for Indian restaurants, called Tandoori. As the Sun sagely put it at the time, Britain had become jalfrezi crazy and the curry industry was booming. In order to stoke this media frenzy, I initiated a number of what I later called curry myths and the mischief-maker in me still gets a thrill when some of them get quoted back to me as gospel truth. I issued a press release to launch the magazine with the assertion that chicken tikka masala was now more popular than roast beef. This was an unverifiable claim but journalists being inherently lazy wanted to believe it to get their story in so didnt bother to check its veracity and it is now widely believed to be true.

Next page