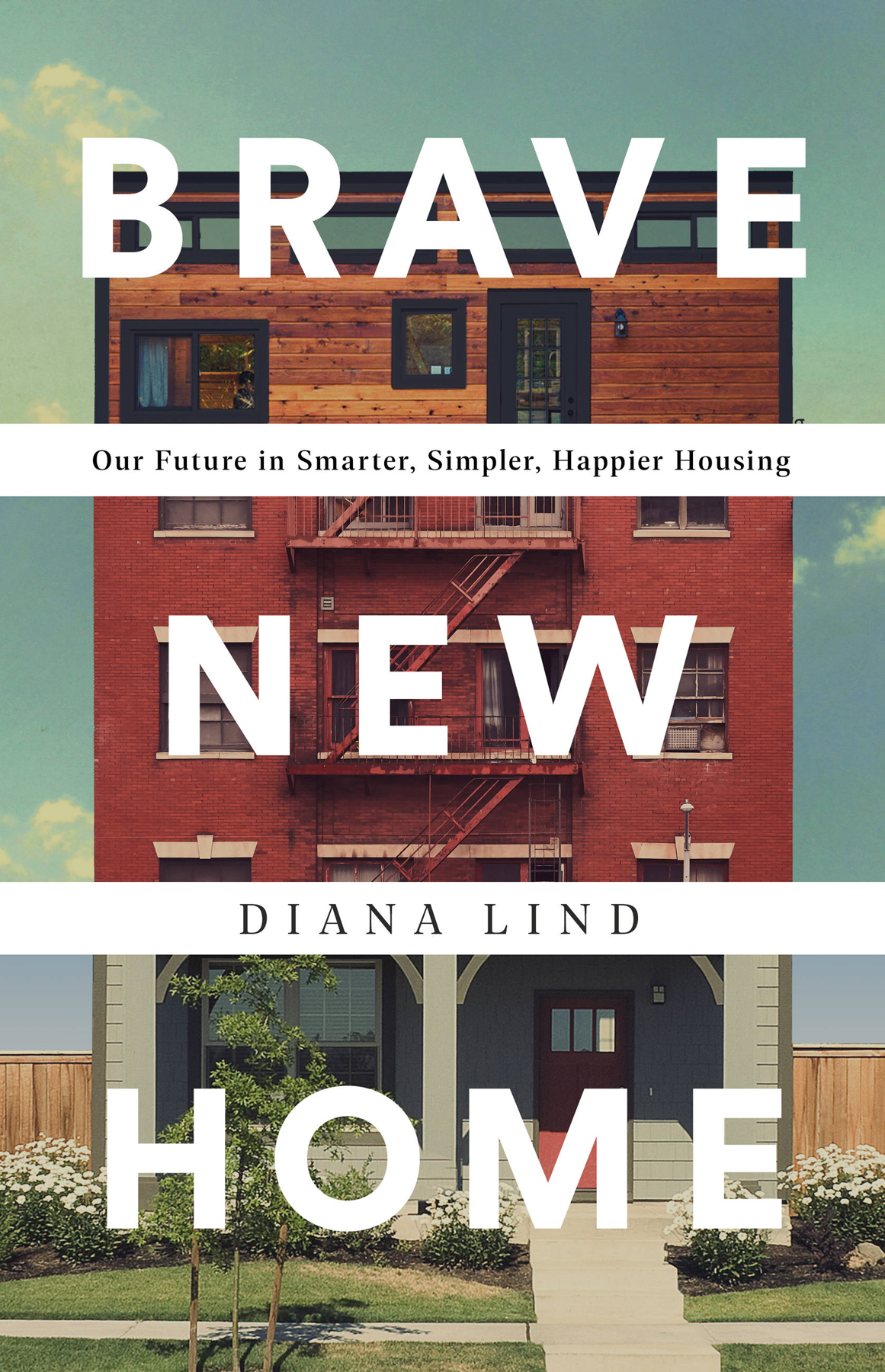

Copyright 2020 by Diana Lind

Cover design by Pete Garceau

Cover images copyright iStock/Getty Images

Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Bold Type Books

116 East 16th Street, 8th Floor, New York, NY 10003

www.boldtypebooks.org

@BoldTypeBooks

First Edition: October 2020

Published by Bold Type Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Bold Type Books is a co-publishing venture of the Type Media Center and Perseus Books.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lind, Diana, author.

Title: Brave new home : our future in smarter, simpler, happier housing / Diana Lind.

Description: First edition. | New York : Bold Type Books, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020020289 | ISBN 9781541742666 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781541742642 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: HousingUnited States. | Housing, Single familyUnited States.

Classification: LCC HD7293 .L49 2020 | DDC 333.33/80973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020020289

ISBNs: 978-1-5417-4266-6 (hardcover), 978-1-5417-4264-2 (ebook)

E3-20200908-JV-NF-ORI

To Greg

B EFORE BECOMING A MOM , I spent little time at home. I was always working, going out to dinner, hitting the gym, discovering new neighborhoods, spending evenings at cultural venues. But when my first son was born, just in time for winter in Philadelphia, that all changed. Now, with a (beautiful!) baby who needed constant feeding, diapering, and attention, I spent a lot of time in our row house. Instead of exploring the city, I explored my own mind, and my home. Before long, I felt uncharacteristically bored and isolatedeven trapped.

When I became a parent, my world became centered around my house, and as a result, my values underwent an unexpected and dramatic transition. Suddenly, my husband and I were spending about an hour every day cooking and doing laundry, and another hour feeding, bathing, and cleaning up after our first son. We scrutinized our $300-per-month gas bill and spent our savings on home repairs. Things I thought I wanted in a home, such as a little extra space, had become just more rooms to clean and heat. Those early months with a newborn can be tough for anyone, but I couldnt help but wonder how humans had survived, and in such quantity, living this waymostly alone, each family for itself.

But people hadnt always lived this way. This style of living, centered around the single-family home, is a relatively new concept in the history of humankind. Up until World War II, families traditionally lived in more communal situations, ranging from multigenerational households to close-knit neighborhoods full of friends and family. The things Id yearned for during my maternity leaveother mothers to learn from, another family to have dinner withwere baked into living that way. Now my options were mommy-and-me classes at $20 a pop and family-friendly restaurants where kids watched YouTube on iPhones while their parents ate dinner.

Out of frustration with my living situation, and a lifelong fascination with cities and the built environment, I began to investigate housing choices in America and their economic, social, and environmental implications. For example, I drew a clear connection between the loneliness I experienced and the amount of time I spent at home. Did other Americans, new parents or not, share my sense of isolation at home? What were the economic and social consequences of people spending the bulk of their income on housing costs? What about the countless hours on household upkeep? How were various trendslike the countrys rising housing costs, increasing social isolation, and decreasing fertility raterelated?

The more I researched these issues, the more I became convinced that the presumed benefits of single-family homes masked their negative social, economic, and environmental consequences. The data suggest that the current housing paradigmpredominantly oriented around owning a single-family homeis unaffordable, unhealthy, and out of step with consumer demand. And a large and growing portion of the population is unable to access the homeownership lifestyle, even if they desire it.

Housing affordability is a crisis, and not just in cities like New York and San Francisco; in Philadelphia, where I live, housing prices rose by 22 percent in a boom period between 2016 and mid-2017. The collision of high prices and limited supply is most acute in coastal cities, but it extends across the country. Utah, a state whose largest city has a little more than two hundred thousand people, created a Commission on Housing Affordability in 2018 to address the states affordable housing gap. In desirable enclaves like Asheville, North Carolina, or Burlington, Vermont, monthly rental costs rival those of Miami and Boston, but average salaries dont.

Not surprisingly, the lack of housing choices and the prevalence of exclusionary housing regulationssuch as minimum lot sizes and required off-street parking for each householdhave made housing grow more expensive, decade over decade. Wages have not kept up with housing costs. In 1988, the typical sale price of a single-family home was 3.2 times the median household income. By 2017, the ratio was 4.2.

Unaffordable housing is not just a problem for those struggling to pay off a mortgage or even for those who are locked To this day, the neighborhoods that were subject to redlining decades ago are still more prone to poverty. Given that homeownership is a significant means of growing wealth in this country, economic disparities between whites and people of color are inevitable.

Unaffordable housing also comes with serious mental and physical health ramifications. High housing costs often result in trade-offs, where families skimp on food and medical attention in order to pay the rent. An examination of the studies tracking the health effects of the 2008 foreclosure crisis found that experiencing a foreclosureand even living near foreclosureswas associated with elevated levels of anxiety, depression, and violent behavior. The CDC report noted that some 68 percent of counselors working with clients to mitigate foreclosure found that many or almost all of their clients appeared depressed or hopeless.

There are also adverse health effects associated with sprawling, single-family suburbanization, including lower rates of walking and social interaction. While there may have once been an urban health penalty of a shorter life span, it hasnt applied for decades (when confounding factors such as race and income are controlled for). Today, life expectancy decreases as level of rurality increases.

There are environmental consequences to single-family housing as well. At a time when the country is grappling with how to address the dangers of climate change and debating the possibility of a Green New Deal, the inefficiency of single-family homes can no longer be ignored. As American homes have become bigger, there have been a variety of environmental impacts: increased emissions from heating and cooling ever-larger private spaces; additional furniture for extra bedrooms, playrooms, and home offices; and additional appliances such as televisions and toilets. All this stuff has a carbon cost.