Foreword

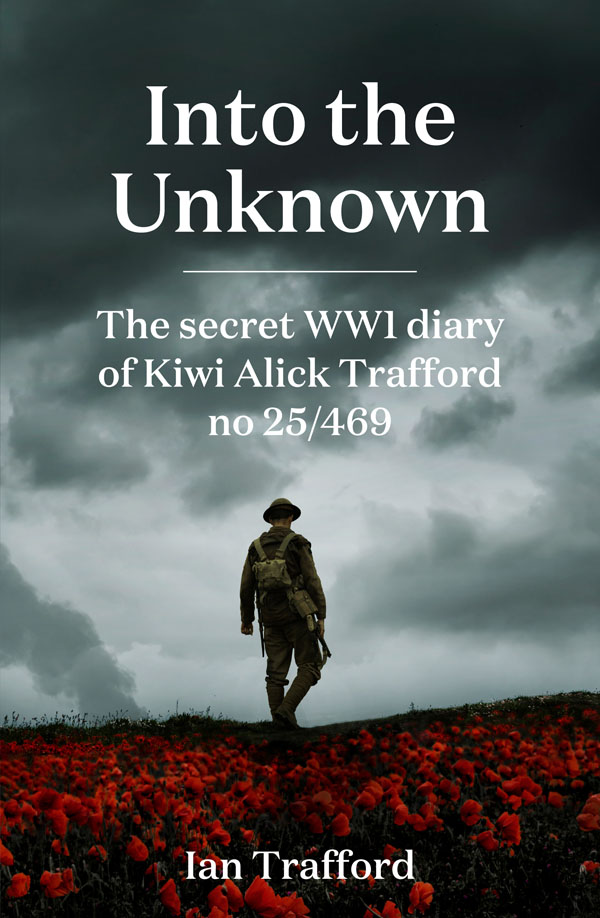

Alick Trafford was a sensitive man born into a rugged life and time. With a head full of thoughts pursuing him into retirement, he bid his son Harvey to enter his ceiling cavity, find a secret package and burn it. There, wrapped in old army waterproof cloth, were his World War One diaries. His only words: They are dynamite.

No son could resist a peek into his fathers hidden past. Alicks deeply hidden mysteries began to weave a moving tale, too personal to intrude upon, but too good to be destroyed.

Being Harveys son, I sensed the diaries sacredness and, even before I left the family fold, I knew one day I would write this book in order to set the record straight about how life really was amidst our un-great war.

Alick was literate and had a love for words. Although illicit in the war, he took a diary almost everywhere, even writing in his trench or dugout right up at the front. His story is raw and emotional. It is not for the faint-hearted or for those bent on glory. No subject is sacred; not death, disaster and dissent, nor romance or soldiers diseases.

He invokes, in truth (often heretically), the trenches and battles, the accelerated life of the times in Egypt, France, Belgium and England, and the occupation of Germany. He details names of friends, how they died and where he, or another, buried them. He feels the pain of everyone. His forays into foreign civvy life are equally as honest, with confessions of depression and the women who stole his heart.

As a reflection of his hectic times, his diary words come jumbling forth in streams of consciousness or jump about in time as he allows himself to recall moments of significance. I have overlaid Alicks words to make them flow and bring them to life. No names have been changed. As he did, I have written without censorship. This is no pro-war story.

In reading this book, we interlope into one mans extraordinary tale, a true tale that resonates with the living kin of 70 million humans entangled in this time.

Alick was my paternal grandfather, an enigma of a man who rarely spoke with me, yet now I speak his voice as if it were mine. I sense and feel his every nuance. I have his genes.

As this book must be in your hands, I thank you.

Ian Trafford

Part 1

The journey beyond

Overseas there came a pleading,

Help a nation in distress.

And we gave our glorious laddies

Honour bade us do no less.

Keep the Home Fires Burning, Lena Guilbert Ford

Chapter 1.

Farewell

1 January, 1916.

Today I am a little nervy for tomorrow I leave the gorge to join my little brother in the war. I am close to wrapping up the last farm jobs on Fathers list. He has been gone a week now, overdue from his trip to the plains, laid up, I believe, from troubles with his rheumy heart. Mama has gone to find him.

In the early morning, I toss grass seed over the hillsides of the Rough Burn, working for a couple of hours until I hear a gunshot, the prearranged signal with my sister Eva, should she need me. Hastening home, I am disappointed to find I have wasted the walk. It was a shot-back from an explosion, let off by horsemen clearing another slip on the bridle track at the Rocky Cutting.

In the afternoon, I load three horses with a hundred pounds each and start away to the back block where the new men, when father brings them, will continue the job felling trees and splitting posts. What a lovely time. The bush track runs steeply uphill and is uneven with tree roots. The incessant showers and rainstorms that wash the gorge have muddied the trail.

On the highest point, the chestnut horse attempts to double back, spooks into swampy ground and sinks up to his stomach. Cursing and floundering, I heave off his load. The poor beast scrambles out with great sucking sounds and immediately bolts for home. I push on with the two remaining horses, until the track, about ten chain from the top camp, becomes so rough their crupper ropes get hopelessly tangled in the whitey woods. With impending darkness, I dump their loads and head back down.

Beneath me, on a terrace beside the creek, the only signs of life are the cheery glow of the kerosene lamp at the window of the hut and a finger of smoke rising from the chimney, layering into gentle wisps above the fledgling poplar row.

I breathe in the scene of our rugged bush block and the receding ridges of the Raukumara Range. I cannot imagine what awaits me far beyond.

I wander through the fire-blackened stumps, shut two killers in the woolshed pen, unlace my boots and head inside to Evas cooking.

Leaving a fitful nights sleep, I sit on the step in the early mist and spit and stroke my blade, then cut the throats of the waiting sheep, punch off their skins, haul out their guts and hang them from the rough-hewn rafters to await my folks return.

As the sun stabs its rays through the whiteness, I saddle up and ride out of the Waioeka. Perhaps forever.