The Hours of the Divine Office are very ancient. They were already ancient in the sixth century when St Benedict codified them in his Rule, a practical guide for the monastic life. They consisted of seven Day Hours together with Vigils, the Night Office (also known as Matins). Each Hour was made up of a selection of prayers, psalms, hymns and readings that changed with the seasons and together spanned the whole twenty-four hours. The exact timing of each of the Hours varied according to whether it was winter or summer and, when Benedicts Rule was adopted by other communities of monks, also from one religious house to another. Vigils was originally said at midnight, but in the Rule of St Benedict was prescribed for the eighth hour of the night 2 a.m. because by sleeping until a little past the middle of the night, the brothers can arise with their food fully digested. Lauds might then follow Vigils immediately or be said separately, three hours later, with a period of study in between. Then came Prime, after which work began, followed three hours later by Terce. Three hours later again came Sext and the main meal of the day. Then came None (pronounced to rhyme with stone), at about 3 p.m., followed by Vespers, often celebrated with great solemnity, at about sunset, and finally Compline, celebrated at 9 p.m., after which the community retired to bed. The Hours still provide the basic structure of monastic life today.

The text of the Office (from the Latin officium, meaning duty or service) was contained in a compendium known as the Breviary. Books of Hours were smaller portable versions of the Office for use by laypeople. They contained a simplified scheme of the eight Hours, known as the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin, together with other prayers and devotions, including the Litany of the Saints, the Seven Penitential Psalms and the Office of the Dead. Books of Hours are the most numerous class of books to survive from the late Middle Ages. They are at once the most visible and the most intimate of medieval books, very widely disseminated yet used in an intensely private manner by individuals, often women, in the privacy of their own chambers. Mass-produced by workshops in France and the Low Countries, they were exported to this country in their thousands the best-sellers of their day. The middle classes bought them ready-made; the wealthy commissioned them splendidly embellished in gold and colours, with special prayers to their patron saints and miniature paintings by the greatest artists of the day into which their own portraits might be incorporated as bystanders looking on at the Nativity, as it were or their favourite castle adopted as the backdrop to some scene of rural life.

First published in Great Britain 2008

Copyright 2008 by Katherine Swift

Illustrations copyright Dawn Burford 2008

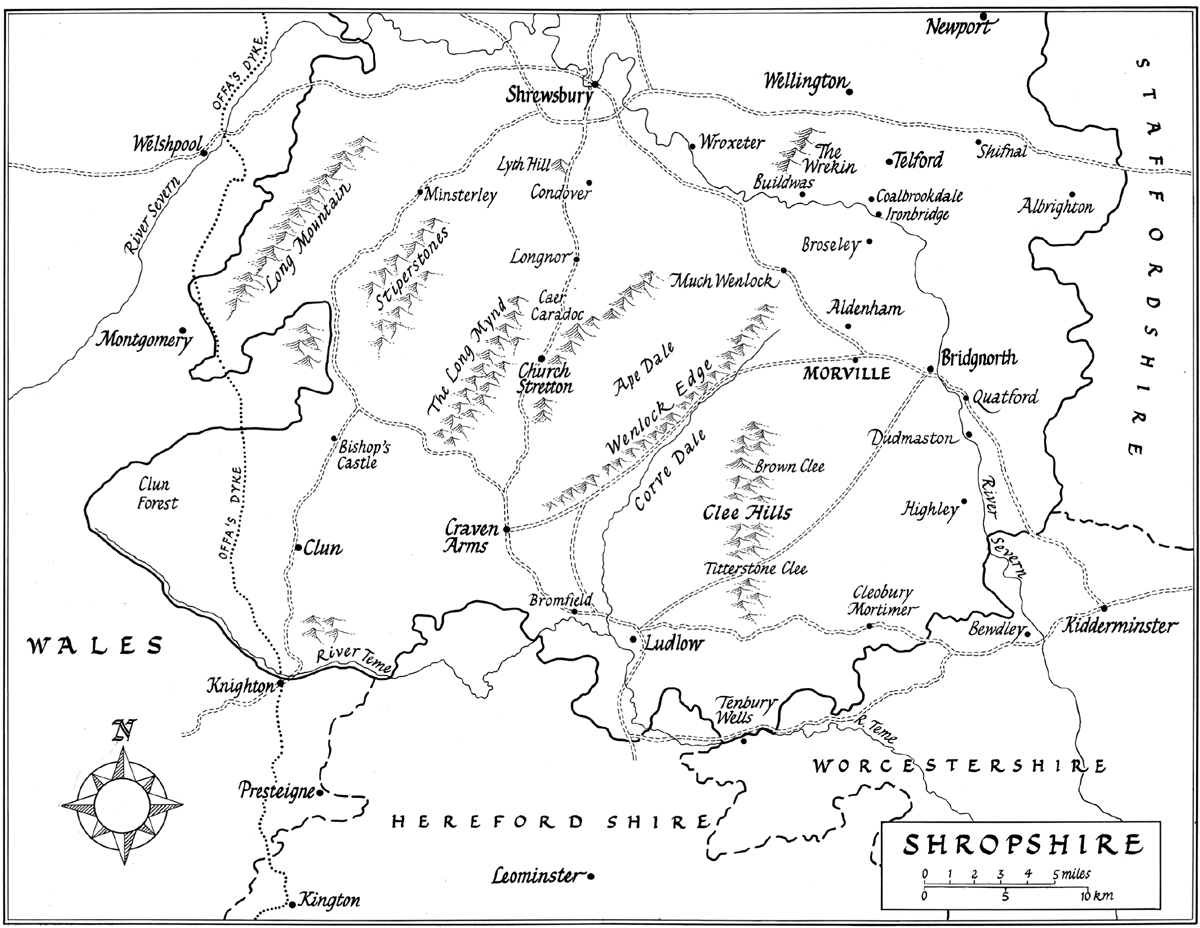

Maps by Reginald Piggott

This electronic edition published 2010 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

The right of Katherine Swift to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Earlier versions of parts of this book appeared in Hortus and The Times

All rights reserved. You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Excerpt from Tales from Ovid by Ted Hughes. Copyright 1997 by Ted Hughes. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC, and Faber and Faber Ltd

Excerpt from The Dry Salvages in Four Quartets, copyright 1941 by T.S. Eliot and renewed by Esme Valerie Eliot, reprinted by permission of Harcourt, Inc. and Faber and Faber Ltd.

Dich wundert nicht /You are not surprised from Rilkes Book of Hours: Love Poems to God by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy, copyright 1996 by Anita Burrows and Joanna Macy. Used by permission of Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Every reasonable effort has been make to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have inadvertently been overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 36 Soho Square, London W1D 3QY

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 4088 2131 2

www.bloomsbury.com/katherineswift

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books. You will find extracts, authors interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

For Harriet and Sophie

Contents

Some people watch birds. I watch clouds. Sometimes its the same thing, as when the buzzards soar on a rising thermal above the garden, or the swifts and house martins chase high-flying gnats on a summers day. But mostly its just clouds I watch: the hard edge of a retreating cumulonimbus, the thin veil of cirrostratus as a warm front comes in, the halo of rainbow-coloured ice crystals around the moon in a mackerel sky. In winter the clouds run down from the north and the east, from the open land beyond the garden; in spring they come bowling up the valley from the south-west, their shadows scudding across the hillside, the fields darkening and brightening with their passage.

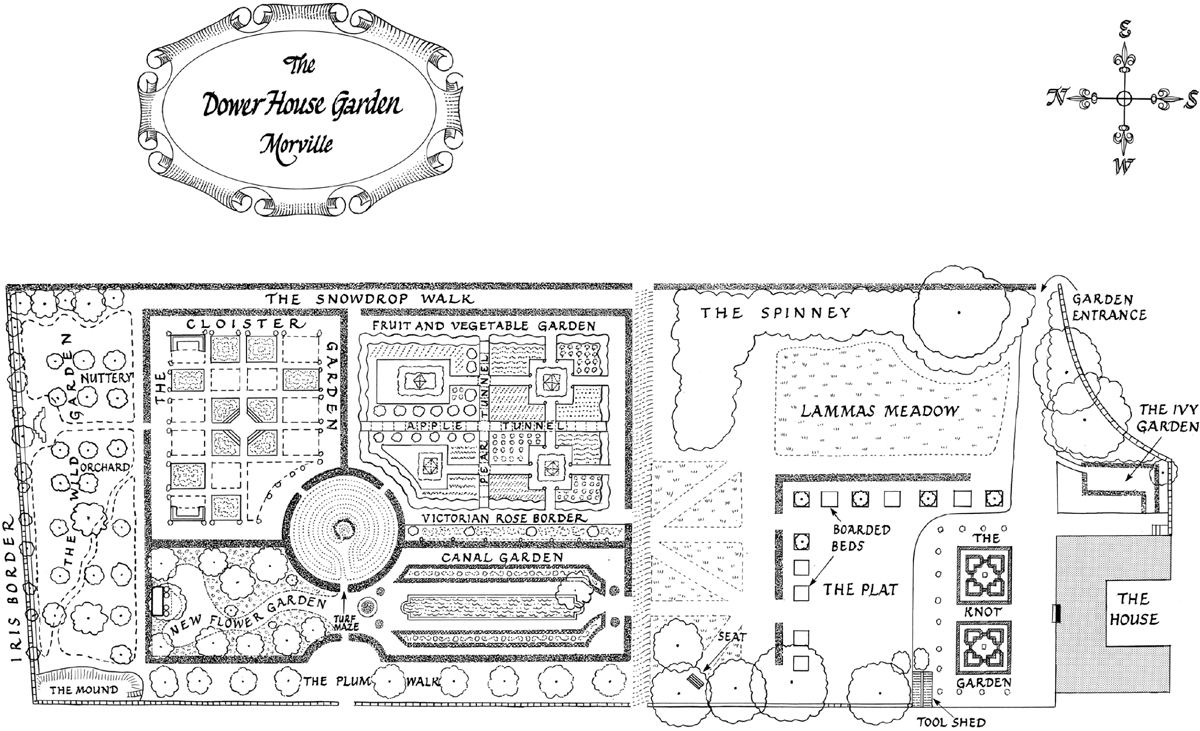

I came here to make a garden. In the red earth I find fragments of blue-and-white willow-pattern china, white marble floor-tiles, rusted iron nails. A litter of broken clay pipes in the flower-beds, their air holes stopped with soil. Opaque slivers of medieval glass, blue as snowmelt. Flat wedges of earthenware dishes with notched rims and looping patterns of cream and brown. Who drank from that cup, who smoked that pipe, who looked through that window? Did they stand as I stand now, watching the clouds on the hillside?

Angles and Romans, Cornovii and Normans, monks and soldiers, herdsmen and farmers; millwrights, iron-founders, carpet-makers and railwaymen, they came this way too following the valley, up from the river, looking for land, iron, work, a home, the hillside brightening and darkening with their ebb and flow. Only the land remains, and the land remembers in crop mark and hollow way, ridge and furrow, bell pit and Roman road, turnpike and stew pond.

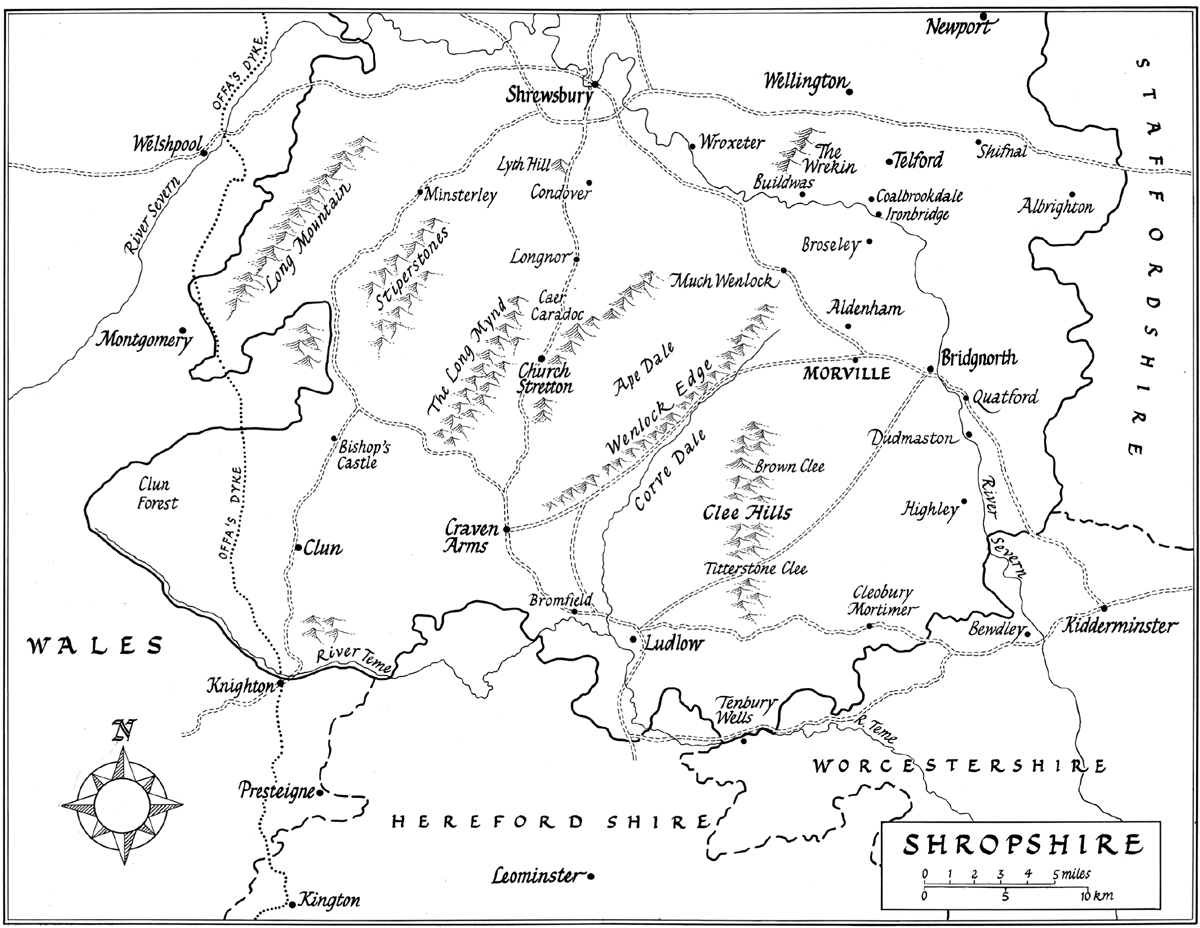

I first came to Morville in the dark; felt, rather than saw, that same high horizon and that round bowl of land. Driving down from the Holyhead ferry in a winter dusk, I made a detour off the old A5 south of Shrewsbury. Night had fallen before I reached Morville. The hairpin bend at the turn to Ludlow was as sharp as it appeared on the map, and there, by the light of the headlamps, were the gate piers to the Hall. I left the car at the end of the drive and walked down the avenue to the house, my feet feeling for the road in the blackness. Emerging from the trees I was conscious of open space curving away from me, and of the dark bulk of the Hall beyond. I kept my distance, half-embarrassed, half-unwilling to be seduced by this new place. I stood, instead, looking across the lawn at the illuminated windows on the first floor, at the light streaming from the narrow embrasures of the turret stair. I could see two pavilions, one on either side, joined to the main house by high curving walls. In the light from the windows, the outline of cupolas was just visible, with a glint of filigree ironwork from the weathervanes above. To the right, the untenanted Dower House; dark, its windows yielding nothing. To the left, a high wooded horizon, black against the first stars. Water rushed somewhere below. And then, high up, behind me, a clock struck the three-quarters two bells combined in a musical phrase of two notes, one high and one low, repeated three times their softly muffled sound drifting out into the darkened valley. A church! I had not expected that.